Step off the subway at Dobutsuen-mae or Ebisucho Station, and you don’t just arrive in another part of Osaka; you slip through a crack in time. Welcome to Shinsekai, the “New World” of a bygone century, a district that defiantly wears its heart, its history, and its neon-drenched soul on its sleeve. This is not the sleek, polished Japan of futuristic cityscapes you might imagine. Instead, Shinsekai offers something far more potent: a raw, unfiltered, and deeply human glimpse into the ambitions and enduring spirit of early 20th-century Osaka. It’s a place built on dreams of Parisian boulevards and New York’s Coney Island, a dream that has since aged, weathered, and settled into a beautiful, gritty patina. To walk these streets is to feel the pulse of the Showa Era, to hear the echoes of laughter from its long-gone Luna Park, and to smell the irresistible, golden-brown aroma of its most famous culinary contribution: kushikatsu. But to truly understand Shinsekai is to understand its rhythm, its people, and its unspoken rules. This isn’t just a guide to a place; it’s an initiation into a culture, a way of life preserved in the savory crunch of a fried skewer and the warm, welcoming glow of a paper lantern. Here, every corner has a story, every meal has a ritual, and every visitor has the chance to connect with a side of Osaka that is as authentic as it is unforgettable.

To fully immerse yourself in this historic atmosphere, consider exploring the vibrant life and housing options in the surrounding Tennoji area.

The Echo of a Forgotten Future

To truly understand the soul of Shinsekai, one must look back to the early 20th century, a time of great change and ambition for Japan. In 1903, Osaka hosted the 5th National Industrial Exposition, a grand event that celebrated the nation’s rapid modernization and industrial strength. The exposition was a huge success, attracting millions and establishing Osaka’s status as a progressive city. The site of the fair then became the foundation for an ambitious new urban development: Shinsekai, or the “New World.” The concept was bold. The southern section was inspired by New York’s lively Coney Island, featuring an amusement park called Luna Park, an engineering marvel of its age. The northern section aimed to capture the elegance of Paris, centered around a striking steel tower. This tower, the original Tsutenkaku, or “Tower Reaching Heaven,” combined elements of the Arc de Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower, symbolizing Osaka’s global ambitions. For a period, Shinsekai represented the future—a dazzling entertainment district alive with cinemas, theaters, restaurants, and the delighted screams of thrill seekers. It was the heart of Osakan modernity, a place to dream, be entertained, and experience the excitement of a new era.

Yet history can be unpredictable. The vibrant promise of Shinsekai began to diminish. Luna Park closed in 1923, and the first Tsutenkaku Tower was sadly dismantled for its metal during World War II. In the following decades, the area was largely neglected, its glamorous past fading into memory. It gained a reputation as a rough, impoverished neighborhood where day laborers congregated, seemingly bypassed by economic progress. Still, this difficult era shaped the unique character that makes Shinsekai so captivating today. It became a refuge for the working class, a stronghold of affordable entertainment and hearty cuisine. This grit became its identity. Cheap and lively kushikatsu restaurants flourished, catering to hungry workers. The narrow lanes of Janjan Yokocho, once a bustling entrance to a red-light district, evolved into a vibrant street of shogi clubs, standing bars, and budget-friendly eateries, its name echoing the shamisen music that once drew patrons. Today’s Shinsekai is not a failed dream but a resilient one—a living museum of the Showa era, with its architecture, signage, and atmosphere preserved not by intentional design, but by a stubborn refusal to change. It is a district that embraces its scars and stories with pride, offering a vivid, tangible link to a past that feels both distant and alive.

The Sacred Rite of Kushikatsu: Decoding the Unspoken Rules

At the core of the Shinsekai experience lies its culinary ritual: kushikatsu. These deep-fried skewers of meat, seafood, and vegetables are far more than just food; they represent a cultural tradition, governed by unwritten rules that every visitor is expected to follow. Disregarding these rules is not simply a social misstep but a breach of a communal trust centered around a shared dipping sauce. Upon entering a kushikatsu-ya, you are welcomed by the sizzling sound of hot oil, the lively clatter of plates, and the warm, savory aroma that promises satisfaction. The environment is lively and casual, with counters filled shoulder-to-shoulder with patrons all joining in this delicious ritual.

The First Commandment: Thou Shalt Not Double-Dip

This rule is paramount—the absolute, non-negotiable law of the place. It is posted on signs, reiterated by staff, and universally understood. The reason is straightforward and based on hygiene. The stainless-steel container holding the dark, sweet, savory tonkatsu-style sauce on the counter is communal, shared by everyone at the table or counter. Once you’ve taken a bite from your skewer, it becomes unclean and must never, under any circumstances, be dipped back into the sauce pot. This rule is an imperative, not a suggestion. Violating it will earn you disapproving glances from fellow diners and a prompt, often emphatic, reminder from the staff. It signifies the ultimate disrespect. The ritual is simple: you receive your freshly fried skewer, hot from the kitchen; you dip it once, generously, into the sauce until well-coated; then, you lift it out and place it on your plate. That single dip is your only interaction with the communal sauce for that skewer.

The Cabbage Loophole: A Tool for More Sauce

What if you take a bite and realize you want more sauce? Don’t worry, the system includes a clever, built-in solution: the complimentary cabbage. A bowl of crisp, raw cabbage wedges is always provided. This serves not just as a palate cleanser or side salad but as your utensil. If you need additional sauce, you take a clean piece of cabbage, dip it into the communal pot, and use it to scoop and drizzle sauce onto the kushikatsu on your plate. This ingenious approach respects the no-double-dipping rule while allowing you to enjoy extra sauce. The cabbage also serves a dual purpose—its crisp, watery crunch contrasts refreshingly with the richness of the fried food, cutting through the oiliness and readying your palate for the next skewer.

The Art of Ordering and Eating

Ordering kushikatsu is delightfully straightforward. Menus typically offer a wide range of skewers, from classic beef (gyu-katsu) and pork (buta-katsu) to more adventurous choices like quail eggs (uzura), lotus root (renkon), shiitake mushrooms, and even cheese. Most places provide an English menu or pictures, making ordering easy for visitors. You can order a few at a time or opt for a set menu (moriawase) to sample a variety. The skewers arrive piping hot, their panko breadcrumb coating perfectly golden brown. When finished, you place your used wooden skewers into a bamboo container at your table. This system allows staff to tally your bill when the meal concludes. It’s an honor system reflecting the casual, trusting atmosphere of these establishments. The ideal companion to kushikatsu is a cold, frothy glass of draft beer (nama biru) or a refreshing highball. The crispness of the drink cuts through the richness of the fried food, creating a sublime culinary harmony that defines the Shinsekai dining experience.

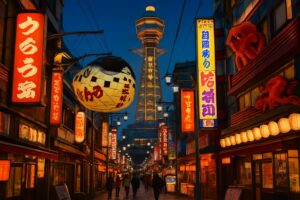

Tsutenkaku Tower: The Sentinel of Naniwa

Dominating the Shinsekai skyline is the district’s unmistakable landmark, the Tsutenkaku Tower. The current structure, reconstructed in 1956 after the original was lost during the war, is a quintessential example of post-war Japanese architecture. Standing at 103 meters, it may be overshadowed by the towering skyscrapers of Umeda, but its cultural significance is vast. Serving as the spiritual heart of the neighborhood, it acts as a beacon of nostalgia, linking the present to the ambitious dreams of the past. Riding the elevator to its observation decks is an experience in itself, often featuring retro-themed interiors and quirky displays. From the top, visitors are treated to a panoramic view of Osaka that is uniquely Shinsekai. Looking down, one can trace the layout of the old Luna Park and observe the sprawling Tennoji Park and Zoo nearby. The view provides context for the district, highlighting its position as a vibrant crossroads between the bustling south of Minami and the more historical areas surrounding Tennoji.

However, the tower’s main attraction for many is found on the fifth floor: the shrine of Billiken. This curious, cherubic figure with pointed ears and a mischievous grin is not a traditional Japanese deity. Created in America by Florence Pretz of Kansas City, Missouri, who claimed to have envisioned the figure in a dream, Billiken was originally a charm doll. The character gained global popularity in the early 20th century, and a statue was installed in Shinsekai’s Luna Park when it opened. Known as “The God of Things as They Ought to Be,” Billiken vanished when the park closed, but a new wooden statue was placed in the rebuilt Tsutenkaku Tower and has since become Shinsekai’s beloved symbol. Visitors from across Japan and around the world line up to rub the soles of his feet, an act believed to bring good luck. The presence of this quirky, foreign-born deity at the center of such a distinctly Japanese district perfectly captures the eclectic, international spirit on which Shinsekai was founded.

Janjan Yokocho Alley: A Corridor of Authentic Life

Stretching along the eastern edge of Shinsekai is a narrow, covered arcade that feels like a world unto itself: Janjan Yokocho. This alleyway serves as the district’s vibrant, pulsing artery. Its name, “Janjan,” is onomatopoeic, believed to mimic the strumming sound of the shamisen that once played to lure patrons to the teahouses and brothels of the nearby red-light district. Today, that history has transformed into a different kind of energy, yet the intensity remains. The alley is just wide enough for two people to walk side by side, and it is lined with a dense array of kushikatsu restaurants, standing bars (tachinomi), shogi (Japanese chess) and go clubs, and affordable canteens serving udon and doteyaki (beef sinew stewed in miso).

Walking through Janjan Yokocho offers a full sensory immersion. The air is thick with the aromas of dashi broth and frying oil. The sounds comprise a cacophony of clacking game pieces from the go clubs, the sizzle of grills, and the loud, cheerful chatter of local patrons. Here, you will witness a cross-section of Osakan society: old men hunched over shogi boards in deep concentration, office workers grabbing a quick beer and a skewer on their way home, and tourists soaking up the chaotic, authentic atmosphere. Many of the establishments have been operating for decades, their interiors worn and rich with character. The food is unpretentious, delicious, and very affordable. To truly experience the local culture, squeeze into one of the tiny standing bars, order a drink, and enjoy a few skewers while standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the residents who call this place home. It’s an experience that can be as intimidating for a first-timer as it is rewarding, offering a genuine connection to the working-class spirit of the city.

The Duality of Day and Night

Shinsekai is a district with two distinct personalities, and to truly appreciate its essence, you need to experience it both in the bright daylight and the electric glow of night. During the day, the neighborhood moves at a slower, more local pace. Elderly residents go about their routines, shogi clubs are filled with regular players, and the streets carry a relaxed, almost sleepy atmosphere. It’s an ideal time for a leisurely walk, admiring the faded facades of old buildings, glimpsing into retro game arcades with vintage machines, and visiting the Tsutenkaku Tower without the evening crowds. The daylight exposes the district’s age, its weathered textures, and details that might be missed in the dark. The sense of history and a community enduring through decades of change is palpable.

As dusk falls, a magical transformation unfolds. One by one, thousands of neon lights and paper lanterns flicker on, bathing the streets in a vibrant, kaleidoscopic glow. The giant fugu (pufferfish) lantern of the famous Zuboraya restaurant (now closed, but its spirit endures) and the ostentatious three-dimensional signs of the kushikatsu chains create a dazzling, almost surreal spectacle. The energy surges dramatically. The streets fill with tourists, after-work crowds, and young people attracted by the retro vibe and affordable eats. The sounds of sizzling oil and cheerful toasts spill from every doorway. Night amplifies Shinsekai’s theatricality and its identity as an entertainment district. It feels like stepping onto a film set for a futuristic city as imagined in the 1980s. The contrast is striking and beautiful. The quiet, nostalgic neighborhood of day transforms into a bustling, electric carnival at night. Experiencing both reveals the full spectrum of Shinsekai’s enduring charm.

Practical Advice for the Intrepid Explorer

Navigating Shinsekai is fairly straightforward, but a few local tips can help make your visit smoother and more enjoyable. The district is most easily reached from two subway stations: Dobutsuen-mae Station on the Midosuji and Sakaisuji Lines, and Ebisucho Station on the Sakaisuji Line. Both stations drop you off right at the edge of the neighborhood, just a short walk from Tsutenkaku Tower.

Although Shinsekai is much safer today than in its more infamous past, it’s still wise to stay aware of your surroundings, especially after dark. The area retains a certain edge, which adds to its charm, but as with any busy urban district, it’s sensible to keep an eye on your belongings. Areas near the elevated train tracks can feel a bit less inviting, so first-time visitors are advised to stick to the main, well-lit streets.

One key thing to keep in mind is that many of the older, smaller businesses in Shinsekai operate on a cash-only basis. While larger chain restaurants may accept credit cards, the true spirit of the district lies in its small, family-run shops. Bringing a reasonable amount of Japanese yen is essential to fully enjoy the local culinary and cultural experiences without any inconvenience. Don’t hesitate to enter places that look a little old or worn; these often have the most character and serve the best food.

Lastly, wear comfortable shoes, as this district is best explored on foot. The real charm of Shinsekai is found not only in its famous landmarks but also in its nameless backstreets and hidden alleys. Allow yourself to wander without a fixed plan, following enticing smells and sounds that draw your attention. Be open and respectful of local customs—especially the sacred kushikatsu rule—and you’ll be rewarded with a truly unique experience.

The Unchanging Soul of the New World

Shinsekai is more than a tourist spot; it stands as a tribute to cultural resilience and the charm of imperfection. In a nation that often prizes the new and immaculate, Shinsekai remains a proud, unapologetic relic of another era. It is a place where the past is not confined to a museum but is alive and present in the streets, kitchens, and hearts of its people. It reminds us that cities are not merely collections of buildings but living entities with memories, scars, and enduring spirits. Visiting Shinsekai means connecting with the very soul of Osaka—a city that is bold, brash, warm, and fiercely proud of its working-class heritage. It’s a place that doesn’t ask for admiration from afar but welcomes you to step inside, pull up a stool, share a meal, and become part of its lively, ongoing story. So arrive with an empty stomach and an open heart, and let the New World reveal the timeless beauty of a dream that refused to fade.