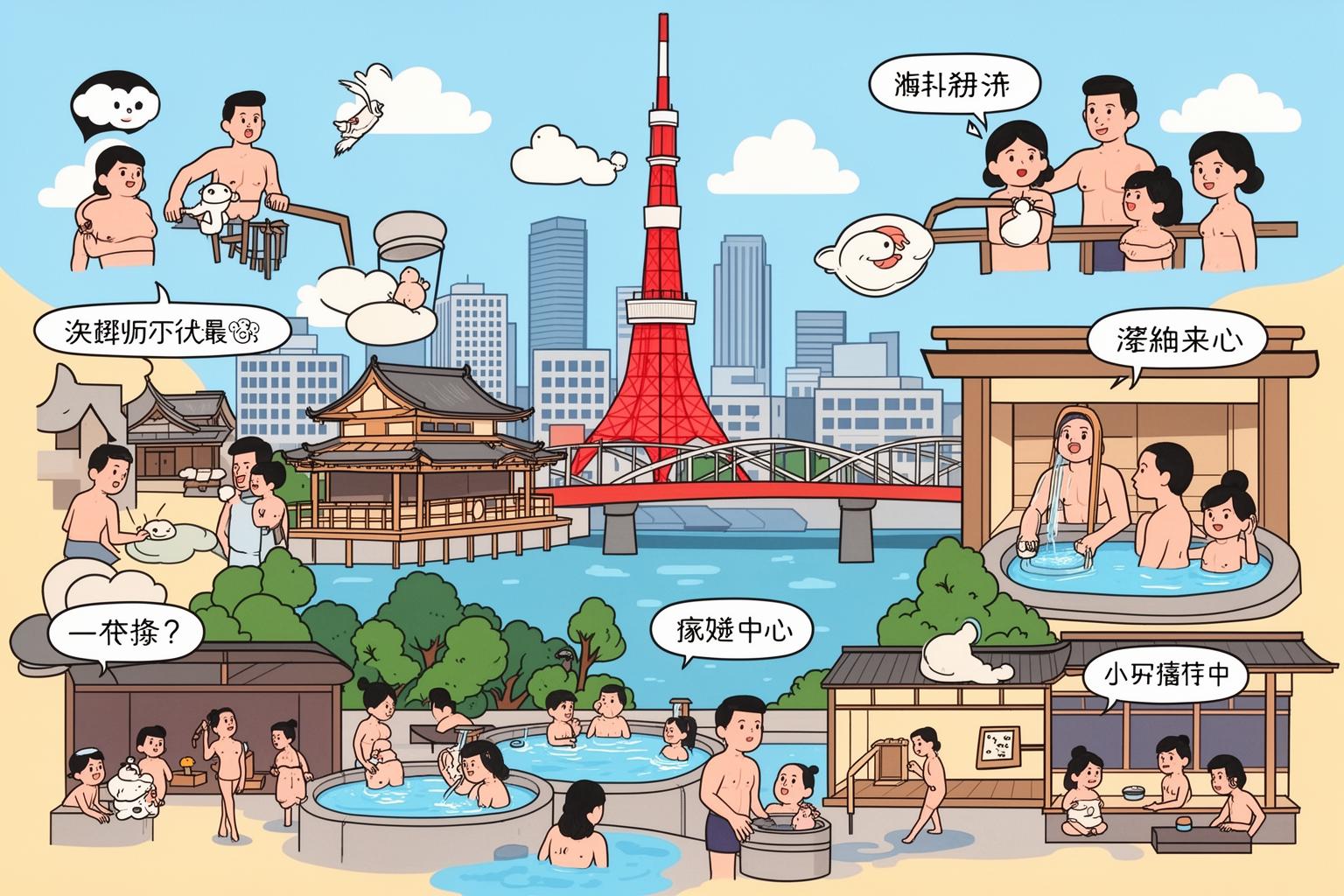

Osaka. The name itself crackles with a certain kind of energy, a kinetic hum that pulses through its neon-drenched arteries and down into the quietest residential lanes. It’s a city of relentless forward motion, of roaring commerce and boisterous laughter, a place that grabs you by the collar and pulls you into its vibrant dance. You feel it in the clatter of the Loop Line, in the sizzle of takoyaki on a cast-iron grill, in the tidal wave of humanity that floods across the Shinsaibashi-suji shopping arcade. It’s intoxicating, it’s thrilling, but it can also be profoundly exhausting. In a city that never seems to sleep, where every moment feels packed with potential, the search for a genuine pause, a place to truly exhale, becomes a quest of its own. You might seek it in a quiet temple garden or a third-wave coffee shop, but to find the city’s true soul, its most authentic form of relaxation, you have to follow the steam. You have to look for the tall, slender chimneys that punctuate the endless rooftops, the humble sentinels marking a sanctuary hidden in plain sight. This is the world of the neighborhood sentō, the Japanese public bathhouse. It is not a tourist attraction; it is a living room. It’s not a spa; it’s a ritual. For a few hundred yen, the sentō offers something far more valuable than a simple bath. It offers a portal into the heart of the community, a warm, wet, wonderful embrace that washes away the grime of the day and connects you to the quiet, steady heartbeat of local life in Osaka. It’s where the city lets its hair down, drops its guard, and reveals its unadorned, beautifully human self. This is your invitation to step through the noren curtain, leave the noise of the metropolis behind, and discover a rhythm of relaxation that has sustained this city for centuries.

To fully embrace the local rhythm, consider complementing your sentō ritual with the daily practice of finding the best deals at Osaka’s local supermarkets.

The Heartbeat of the Block: What is a Sentō, Really?

Before you take your first dip, it’s important to recognize that a sentō is quite different from the well-known onsen, or natural hot springs, that often feature in travel brochures. An onsen is a destination—a gift from nature—drawing its charm from volcanically heated, mineral-rich water. By contrast, a sentō serves as a community cornerstone. Its water is warmed by a boiler, and its appeal comes from the people who gather there day after day. It is a necessity turned cultural institution, deeply embedded in daily life, offering stability amid a city of constant change.

Beyond the Bubbles: More Than Just a Bath

The history of the sentō parallels the history of urban Japan. For centuries, most houses lacked private bathing facilities. The sentō was not a luxury but a vital part of hygiene and public health. However, it soon became so much more. It grew into a social hub where merchants, laborers, and housewives could undress and leave behind the rigid social hierarchies of the outside world. This practice, called hadaka no tsukiai or “naked communion,” is central to the sentō experience. It reflects the idea that without signs of status—the tailored suit, the work uniform, the expensive watch—everyone is simply human. In the steam, barriers fade, and more genuine, open communication arises. Today, even though most homes have their own baths, the sentō persists because of this social role. It’s a place where elderly residents fight loneliness, parents teach children bathing rituals, and neighbors share local gossip while soaking side by side. It stands as a living testament to the power of shared spaces and simple human connection.

A Symphony of Sights and Sounds

Stepping into a classic Osaka sentō is like entering a carefully preserved time capsule. Your senses are immediately captivated by a rich array of details. Visually, the first thing you might notice is the artwork. Above the tubs, a magnificent mural often dominates the wall. While Mount Fuji’s iconic image represents stoic Japanese beauty, in Osaka you may see grand koi fish, peaceful bamboo groves, or local landmarks depicted in exquisite tile mosaics. The tilework throughout the bathhouse is often a spectacle itself—featuring intricate geometric designs, delicate floral patterns, and vibrant colors that have been meticulously cleaned for decades. Look down to see worn stone floors; look up to admire a high wooden-beamed ceiling designed to release steam. The changing rooms, or datsuijo, showcase thoughtful, functional design, with rows of wooden lockers secured by clunky wooden keys or elastic wristbands. The sounds create a unique urban symphony: the rhythmic splash of faucet water, the hollow echo of plastic stools sliding across tile, the soft murmur of conversations in the Kansai dialect, the clatter of a wooden bucket—or oke—being set down. You may catch the distant rumble of a train, the whir of an old-fashioned fan in summer, or the cheerful chime of the front door welcoming new arrivals. The air itself is thick with the clean, elemental scents of hot water, steam, soap, and occasionally the faint, pleasant aroma of cypress or hinoki wood. It is a full sensory experience that clearly signals you have stepped out of the ordinary world.

Your First Dip: A Step-by-Step Guide to Sentō Serenity

The idea of bathing with strangers might seem intimidating to those unfamiliar with the practice. However, the process follows a straightforward, logical set of rituals that are easy to adhere to. Rather than viewing these as strict rules, think of them as a graceful choreography designed to ensure everyone can share the space comfortably and hygienically. Mastering this routine is your key to experiencing a deep state of relaxation.

Crossing the Threshold: From Street to Sanctuary

Your journey begins on the street. Look for the distinctive temple-style roof common to many older sentō, and, more importantly, the kanji character 湯 (yu), meaning “hot water.” You’ll often see it displayed on a sign or on the short, split curtain hanging in the doorway, known as a noren. This noren symbolizes the boundary between the outside world and the inner sanctuary. Passing through it signifies consciously leaving your worries behind. Typically, the noren is blue or dark navy for the men’s entrance (男) and red or pink for the women’s entrance (女). Once inside, you enter a small entryway where you must remove your shoes, placing them in one of the small shoe lockers (getabako) provided. From there, you approach the central reception desk, called a bandai. In older establishments, it’s a high, seated platform where an owner—often a kindly grandmother or grandfather—oversees both the men’s and women’s sides. In more modern sentō, it resembles a typical front counter. Here, you pay the bathing fee, regulated by the local government and usually quite affordable—around 500 yen. If unprepared, you can purchase a tebura set (“empty-handed set”) that includes a small bar of soap, a single-use shampoo packet, and a rental towel. Even if you bring your own supplies, renting or buying the two essential towels—a small one for washing and a larger one for drying—is common. This transaction marks your official entry into the bathing community.

The Changing Room (Datsuijo): Rituals of Preparation

After paying, proceed into the designated changing room. The atmosphere is calm and purposeful. Find an empty locker—some use keys, others have open cubbies with baskets for belongings. This is the moment to get completely undressed. For many from Western cultures, this can be the biggest challenge. It’s important to understand that nudity in a sentō is completely non-sexual and free of judgment. Everyone, regardless of age, shape, or size, is there for the same reason: to get clean and relax. Body awareness quickly fades when you realize no one is paying attention. The only items you take into the bathing area are your small wash towel, often called a “modesty towel,” along with soap and shampoo. You may use this small towel to loosely cover yourself while walking from the changing room to the washing area, though many locals do not. Its primary roles are for scrubbing your body and later placing on your head while soaking. Store your clothes and large bath towel neatly in your locker or basket, secure it if there’s a key, and prepare to enter the main bathing hall.

The Washing Area (Araiba): The Cardinal Rule of Cleanliness

If there’s one unbreakable rule in the sentō, it’s this: you must wash your entire body thoroughly before entering the communal tubs. This is a matter of hygiene and respect for fellow bathers. The bathing hall has two main sections: the washing stations, or araiba, and the bathtubs, or ofuro. The washing stations line the walls and consist of a series of low plastic or wooden stools positioned before faucets that usually have both a fixed spigot and a handheld shower wand. Take a stool and bucket (oke), then find an empty station. Sit on the stool—it is considered rude to wash standing, as it risks splashing others. Use the bucket or shower wand to soak yourself completely with hot water, rinsing away the day’s initial grime. Then, lather your small towel with soap or body wash and scrub yourself thoroughly from head to toe, including washing your hair. Once you are fully clean and free of suds, rinse your stool and the surrounding area. Only then are you ready for the next step.

The Main Event: Soaking in the Tubs (Ofuro)

With your body clean, you can finally approach the tubs. This is the reward. Enter the water slowly, allowing your body to adjust to the heat, which can be quite intense (typically between 40 and 44 degrees Celsius). The etiquette here is simple: your small wash towel should never touch the bathwater. Most people either fold it neatly and place it on their head—which can help prevent dizziness from the heat—or leave it on the tiled edge of the tub. The tubs are for soaking, not swimming or washing. Find a comfortable spot, lean back, and let the heat take effect. You’ll feel your muscles relax, your joints loosen, and the tension in your shoulders begin to dissipate. Most sentō offer a variety of tubs. Usually, there’s a main tub with very hot water (atsuyu) and sometimes a cooler one (nuruyu). You might also encounter a jet bath (denki buro) with powerful jets massaging your back and legs. A word of caution: the denki buro passes a low electrical current between two plates, creating a tingling, muscle-contracting sensation; some find this therapeutic, others alarming—approach with caution! Many sentō also have a small, deep cold tub, the mizuburo. Alternating between hot tubs and cold plunges is invigorating, stimulating circulation and leaving a pleasant, tingling sensation. The art lies in finding your rhythm, listening to your body, and simply being present in the moment.

The Unspoken Language: Navigating Sentō Social Cues

Beyond the practical guidelines, there is a subtle social etiquette that shapes the sentō experience. It’s less about strict rules and more about fostering an atmosphere of mutual respect and consideration. Grasping this unspoken code will help you feel less like a visitor and more like an active participant in this cherished local tradition.

To Talk or Not to Talk?

One of the most frequent questions from newcomers is whether they should engage in conversation with strangers. The simple answer is: it’s your choice. The sentō is naturally a social space, and for many regulars, it serves as a key place to catch up with friends and neighbors. You will hear lively chatter and laughter, and it’s perfectly acceptable to enjoy these sounds without joining in. No one will think you rude for seeking quiet reflection. In fact, many come specifically for that silent retreat. However, if you’re willing, the sentō can be a wonderful place to connect. A simple nod, a quiet konbanwa (good evening), or a remark about the warmth of the water can open the door. Don’t be surprised if an older gentleman or lady strikes up a conversation, curious about your origins. These exchanges, often conducted in simple Japanese, can be some of the most genuine and heartwarming you’ll experience in Osaka. Be open, be respectful, and don’t feel pressured. Follow the example of those around you and find a level of interaction that feels comfortable.

Tattoos and Taboos

Tattoos present a significant issue in Japan’s bathing culture. Historically linked to the yakuza (Japanese organized crime), tattoos have long been prohibited in many public bathing facilities, especially upscale onsen and fitness clubs. This can cause anxiety for foreign visitors with ink. The good news is that neighborhood sentō, especially in an approachable city like Osaka, tend to be far more relaxed. Many have completely dropped such restrictions, acknowledging that tattoos are now a global form of self-expression. You will often see signs near the entrance explicitly welcoming tattoos. In fact, you’re likely to find many tattooed Japanese people, both young and old, enjoying the baths alongside everyone else. If unsure, it’s best to check the sentō’s policy online if available or simply look for signs at the entrance. If you have small tattoos, using a waterproof “tattoo cover” bandage can be an option. But for the most part, if you choose a local, straightforward sentō, you’ll discover a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. This is another way the sentō serves as a great equalizer, focusing on the shared experience rather than superficial differences.

The Rhythm of Respect

The social fabric of the sentō rests on a foundation of mutual respect. This is shown through small, considerate actions that together create a harmonious environment. Beyond the essential rule of washing first, this means avoiding splashing water on others at your washing station. It means wringing out your small towel away from the main baths. It means not occupying more space than necessary, both at the washing stations and in the tubs. When finished at your washing area, rinse the stool and floor with your bucket for the next person. Before returning to the changing room, use your small, damp towel to lightly dry off, preventing water from dripping onto the floor. These are not difficult rules to follow; they are simply the common-sense gestures of people sharing a beloved communal space. By observing and embracing these practices, you show respect for the establishment, its patrons, and the culture itself.

The Post-Bath Glow: The Ritual Continues

Your sentō experience doesn’t conclude the moment you step out of the hot water. The period immediately following the bath, called yuzame, is an essential part of the ritual. It’s a time to gradually return to the world, to savor the deep warmth lingering in your bones and the profound calm settling in your mind. Hastening this final step would be like gulping down a fine wine—you’d miss all its best notes.

The Art of Cooling Down

After your last soak, rinse off at the washing stations one final time and head toward the changing room. As mentioned earlier, a quick wipe-down with your small towel before entering is considered good manners. Now you can finally use your large, dry bath towel. Take your time drying off completely. In the changing room, you’ll find a variety of charmingly retro amenities. There might be coin-operated hair dryers that roar to life for three minutes with a 20-yen coin. You may spot an old, sturdy massage chair that can pummel your back for 100 yen. Almost certainly, there will be an ancient mechanical weight scale where you can step on to see how much water weight you’ve lost through sweat. This is the moment to simply sit on one of the benches, wrapped in your towel or the provided cotton yukata, and allow your body temperature to slowly normalize. You’ll experience a pleasant, light-headed languor—a state of pure, uncomplicated contentment.

The Nectar of the Gods: Post-Sentō Refreshments

This is arguably the most universally cherished part of the entire sentō ritual. Rehydrating after a prolonged, hot soak is crucial, and the sentō offers the most satisfying way to do so. In the changing room or the small lobby, you will find a vending machine or refrigerated case stocked with drinks. The undisputed favorite post-sentō beverage is fruit-flavored or coffee-flavored milk (gyūnyū), served in an iconic glass bottle with a simple paper cap. There is something irresistibly perfect about chugging a cold, sweet coffee milk while your body still radiates warmth from the bath. For many Japanese people, it’s a taste of childhood and a core memory of the sentō experience. Other popular options include sports drinks like Pocari Sweat to replenish electrolytes, or a crisp, cold Japanese beer. Sitting down in the lounge, perhaps chatting briefly with the owner or another bather while sipping your chosen drink, offers the perfect conclusion to the experience. It seals in your relaxation and gently eases you back into the outside world.

Extending the Evening

For many locals, the sentō serves as the centerpiece of an ideal evening. Freshly scrubbed and thoroughly relaxed, it’s the perfect state for enjoying a good meal. Many neighborhoods are designed around a sentō, surrounded by small, family-run eateries. A typical routine is to end the sentō visit and then stroll, still glowing, to a nearby izakaya (Japanese pub), ramen shop, or okonomiyaki restaurant. Food and drink simply taste better after a sentō. A cold beer has never been so crisp, a bowl of hot noodles never so comforting. Incorporating your bath into this broader evening ritual is key to making it a meaningful part of your life in Osaka. It transforms the act of bathing from simply getting clean into a holistic experience of well-being and pleasure—a perfect way to mark the end of a long day or begin a relaxed weekend night.

Finding Your Sentō: An Explorer’s Guide to Osaka’s Baths

Once you become comfortable with the process, the true joy lies in exploration. Osaka is dotted with countless sentō, each boasting its own unique character, history, and charm. Discovering them is like urban treasure hunting. Rather than providing a definitive list that might spoil the fun, here are the archetypes you’re likely to encounter on your quest to find your sentō.

The Time Capsule Sentō

These represent the crown jewels of the sentō world. Often housed in stunning wooden buildings with sweeping, temple-like karahafu gables, these establishments have been run by the same family for generations. Stepping inside feels like walking onto a film set from the Showa Era (1926-1989). You’ll find all the classic features: the high bandai platform, creaky wooden lockers, exquisite tile murals, and perhaps even a small, beautifully tended courtyard garden visible from the changing room. The water might be heated by a traditional wood-fired boiler, lending it a special softness. These places are rich in history and quiet dignity. You can find these gems tucked away in the backstreets of older neighborhoods like Nishinari, Taisho, or around the Tennoji temple complex. They offer the most atmospheric and historically immersive sentō experience.

The Modern “Super Sentō”

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the “Super Sentō.” These large, modern complexes expand the basic concept of the public bath into a full-day entertainment facility. While they lack the neighborhood intimacy of a traditional sentō, they offer an impressive array of amenities. You’ll find dozens of different types of baths: carbonated baths, herbal baths, open-air rotenburo with views, and multiple saunas at varying temperatures. Beyond bathing, they usually feature multiple restaurants, extensive manga libraries, nap rooms with reclining chairs, and professional massage and spa services. Spa World in Shinsekai is an extreme, theme-park-like example. Though fantastic and enjoyable in their own right, they are an entirely different experience. They serve as destinations for a day of pampering, whereas neighborhood sentō are rituals woven into daily life.

The Neighborhood Gem

This is the category where you’ll find your home base. These sentō fall somewhere between the historic time capsule and the modern super sentō. They’re clean, well-maintained, and deeply integrated into the local community but may have been updated over time. Perhaps they’ve added a sauna, a modern jet bath, or a small rotenburo. The owner might be younger, bringing fresh energy to the business. These are the workhorses of the sentō world, truly serving the daily needs of their surrounding residents. The best way to find them is simply to explore on foot or by bicycle. As you wander through Osaka’s residential areas, keep an eye out for tall chimneys. Alternatively, use a tool like Google Maps and search for the Japanese term for sentō: 銭湯. Trying a few different ones near your apartment is part of the fun. Each will have a slightly different water temperature, layout, and cast of regulars. The journey toward finding the one that feels just right—where the owner begins to recognize you and the water feels like it was heated just for you—is a deeply satisfying part of living in this city.

A Deeper Current: The Sentō’s Place in Japanese Culture

To truly appreciate the sentō, it is helpful to understand the profound cultural currents that run through it. The simple act of communal bathing is linked to ancient traditions and philosophies that are fundamental to the Japanese worldview. It is more than merely a custom; it embodies core cultural values in a tangible way.

The Philosophy of Hot Water

Japan’s love of bathing is deeply connected to the purification rituals of Shintoism, the nation’s indigenous religion. The practice of misogi involves cleansing the body with water to remove not only physical dirt but also spiritual impurities, or kegare. This idea has permeated secular culture, shaping the belief that a hot bath does more than clean the skin. It is considered a means to wash away fatigue, stress, and worries, serving as a ritual of renewal that purifies the spirit and readies one for peaceful rest. This explains why bathing is usually an evening ritual in Japan, marking the close of the day’s work and the start of personal time. The sentō also reflects the Japanese appreciation for the seasons. Many bathhouses create special baths to celebrate particular times of year. On the winter solstice, you might find a yuzu-yu, with tubs filled with fragrant yuzu citrus, believed to prevent colds. On Children’s Day in May, there might be a shobu-yu, a bath infused with iris leaves, thought to encourage good health and vitality. These thoughtful details link the daily bathing ritual with the broader cycles of nature.

A Fading Tradition? The Future of the Sentō

Despite its deep cultural significance, the neighborhood sentō faces an uncertain future. With nearly every home in Japan now having a private bathroom, the sentō’s original function has become less necessary. This challenge is compounded by rising fuel costs, aging buildings needing costly repairs, and many sentō owners being elderly without successors to continue the family business. Each year, dozens of these cherished establishments close permanently, and with every closure, a small piece of community history disappears. However, there is a growing movement to protect and revitalize them. A new generation of owners, artists, and architects are reimagining what a sentō can be. They are renovating old bathhouses with a modern design while preserving historic charm. They are transforming them into lively community spaces by adding craft beer taps, hosting live music, or incorporating art galleries. They use social media to engage a younger audience and showcase the unique appeal of sentō culture. When you choose to visit a neighborhood sentō, you do more than take a bath. Your 500 yen is a vote—a small investment in preserving a vital cultural treasure. You become an active participant in sustaining this beautiful, centuries-old tradition for future generations.

Weaving It In: Making the Sentō Your Osaka Ritual

The final step is to shift from simply trying the sentō once to making it a consistent part of your life in Osaka. This is when the real benefits—stress relief, better sleep, and a deeper sense of community—begin to emerge. It’s about establishing a habit, a personal ritual that you can genuinely look forward to.

Your Sentō Starter Kit

To make frequent visits convenient and spontaneous, create your own ofuro setto, or bath kit. Find a small, waterproof basket or bag. Inside, keep your favorite soap or body wash, shampoo and conditioner, a razor, and any other toiletries you prefer. The essential items are two towels: a small, thin one for washing (a Japanese tenugui towel works perfectly, as it’s lightweight and dries quickly) and a larger towel for drying off. Having this kit packed and ready by your door means you can head to the sentō on a whim without the hassle of gathering your supplies each time.

Finding Your Time

Try different times to discover what fits best into your routine. For many, the ideal moment is right after work, serving as a clear psychological transition that washes away the stress of the office and marks a clean break before the evening begins. Others prefer a long, leisurely soak on Sunday afternoons as a way to reset and prepare for the week ahead. Visiting the sentō after a gym workout or a long bike ride is an excellent way to soothe sore muscles. Think of it as a healthier, more affordable, and more satisfying alternative to other ways of unwinding. Rather than heading straight to a bar for a drink, try going to the sentō first—you’ll find that a post-bath beer is twice as enjoyable.

The Slow Reward

Above all, remember that the sentō counters the rushed pace of modern life. Don’t try to squeeze it into a tight schedule. Give yourself the gift of time. Plan for at least an hour, preferably longer. The aim isn’t to get clean as quickly as possible but to slow down, fully experience your body, and reconnect with the simple, profound pleasure of hot water and quiet reflection. Let the natural rhythm of washing, soaking, cooling, and rehydrating unfold at your own pace. This is your time. No deadlines, no emails, no notifications—just steam, water, and the gentle hum of a community at rest.

The Warmth That Lingers

In the vibrant, bustling story of Osaka, the neighborhood sentō serves as a quiet, poetic chapter. It invites you to step away from the main stage and explore the intimate, behind-the-scenes life of the city. It’s a place to find warmth—not only from the scalding water of the tubs but also in the easy camaraderie of shared space, the kindness of the owner’s familiar nod, and the sense of belonging to a community, even if only for an hour. As you walk home through the cool Osaka night, skin tingling and clean, mind calm and clear, you carry that warmth with you. It’s a feeling that lingers long after the water has dried, a deep sense of peace and place. You realize you haven’t just taken a bath; you’ve participated in a ritual that has comforted and cleansed generations. You’ve connected with the steam and soul of the city, and in doing so, you’ve found a small, warm piece of home.