Yo, what’s up, Osaka? Taro Kobayashi here. When you hear the name ‘Kishiwada,’ what’s the first thing that hits you? For most, it’s a sound. A thunderous, ground-shaking roar that rips through the September air. It’s the sound of thousands of voices screaming in unison, the rhythmic chant of men pulling thick ropes with every ounce of their being, and the bone-rattling rumble of wood on asphalt. This is the sound of the Kishiwada Danjiri Matsuri, one of Japan’s most electrifying and downright dangerous festivals. You see these massive, ornate wooden floats, or ‘danjiri,’ weighing upwards of four tons, careening through narrow city streets at full speed, executing hairpin turns that defy physics. It’s a spectacle of pure, unadulterated kinetic energy. But here’s the thing, a question that started buzzing in my head the first time I witnessed this controlled chaos: what happens when the festival ends? When the crowds go home and the last echo of the chant fades? These incredible wooden beasts, these moving temples of art and engineering, they don’t just get parked in a garage and forgotten. No, their journey, their very life, is a cycle. And at the heart of that cycle is a group of artisans whose work is as intense and demanding as the festival itself, but largely happens in the quiet months, hidden from view. I’m talking about the `Daiku-gata`, the master carpenters of the Danjiri. Their festival isn’t just two days in September; it’s a 365-day-a-year devotion, a conversation with wood, tradition, and the soul of their city. This isn’t just about building a float; it’s about upholding a legacy, one chisel mark at a time. Let’s pull back the curtain and step into their world.

To truly appreciate the dedication of Kishiwada’s master carpenters, one must understand the full spectacle of the Kishiwada Danjiri Matsuri they tirelessly prepare for all year.

The Roar of September: Understanding the Danjiri Spectacle

To truly grasp what these carpenters accomplish, you first need to understand the incredible demands placed on their creations. The Kishiwada Danjiri Matsuri isn’t just a parade; it’s a high-speed, high-stakes display of community strength and precise maneuvering. This festival, a prayer for a bountiful harvest since 1703, today serves more as a tribute to the spirit and pride of each neighborhood that fields a danjiri. Each float represents a specific city district, and the rivalry is tangible—a friendly yet fierce competition that energizes the entire event.

A Festival Born of Speed and Spirit

The highlight, which attracts nearly half a million spectators, is the `yarimawashi`. This is where danger and magic truly converge. Imagine a four-ton wooden structure—top-heavy and ornate—being pulled by up to 500 people, racing toward a sharp 90-degree turn at full speed. The front pullers release their ropes, the rear pullers dig in their heels, and a team using levers wedged into the front wheels pivots the massive float around the corner without losing momentum. It’s a move that is both violently forceful and gracefully executed. The danjiri creaks, its wooden joints screaming under intense torsional stress. On the roof, the `daikugata`—the carpenter—dances and leaps, his feet intimately familiar with every inch of the wood. He’s more than a passenger; he’s the navigator, the cheerleader, and the living spirit of the float, signaling directions with his fan, mirroring the chaos below in his movements. His role is to read the float’s momentum and the crowd’s energy, entrusted only to a true master who knows the danjiri inside and out. The atmosphere is electric, thick with the scent of festival food, sweat, and the faint sharpness of Keyaki wood being pushed to its limits. The sounds overwhelm the senses: the rumble of wooden wheels, sharp commands from team leaders, the crowd’s roar, and the pounding of traditional drums and bells from within the float. For a first-timer, it’s an exhilarating sensory overload. For the carpenters who built it, every successful `yarimawashi` is both a moment of sheer terror and ultimate validation. Their craftsmanship endures. The spirit lives on.

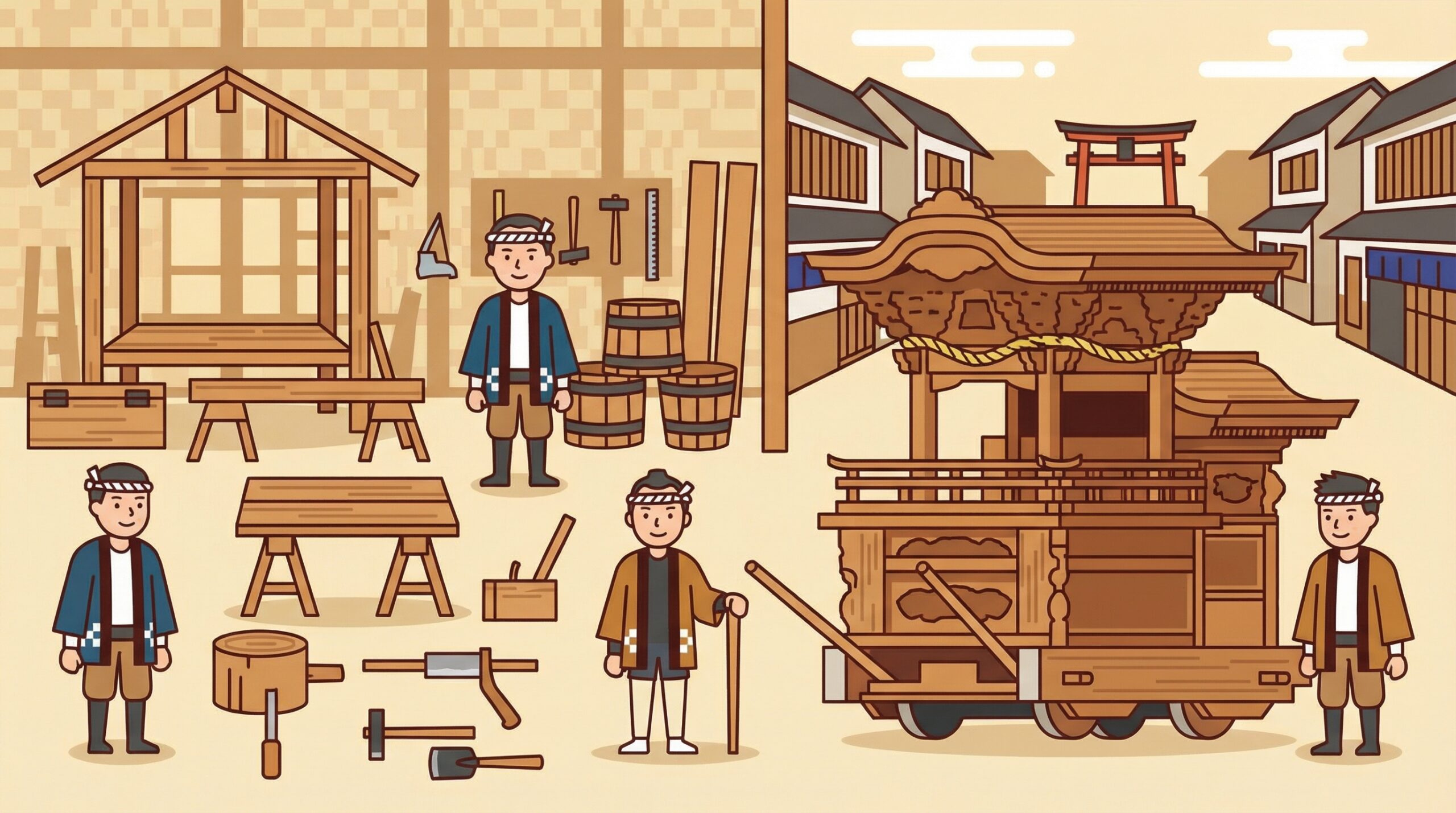

The Danjiri: Beyond Just a Float

Let’s take a closer look at what a danjiri really is. It’s a masterpiece of Japanese woodworking—a mobile piece of architectural art. Every part is crafted from wood, primarily the prized Keyaki, or Japanese Zelkova. As someone familiar with trees, I can say Keyaki is exceptional. It’s incredibly dense, hard, and boasts a stunning grain, making it ideal for the stresses of the festival. Yet, it’s also very challenging to work with. The primary structure contains no nails, screws, or bolts. Instead, the entire frame is held together by a complex system of interlocking joints called `kumiki`. This ancient technique offers the structure flexibility, allowing it to absorb the shocks of the road and the G-forces of sharp turns. This brilliant design lets the danjiri move almost like a living being rather than a rigid box.

However, the true soul of the danjiri lies in its carvings, the `horimono`. The entire float—from base to multi-tiered roof—is adorned with breathtakingly intricate wooden sculptures. These aren’t mere decorations; they’re three-dimensional history books. Each panel narrates stories, often drawn from classic Japanese military epics such as the ‘Taiheiki’ or the ‘Tale of the Heike,’ portraying famous samurai battles, heroic moments, and legendary creatures. The detail is astonishing: you can see a warrior’s facial expression, the texture of his armor, the tense muscles of his horse. These carvings are crafted by specialized master artisans known as `horimono-shi`, who may spend months or even years creating a single set of panels for a new danjiri. The float becomes a moving museum, a rolling homage to the nation’s history and the town’s identity. Owning and maintaining a danjiri is a tremendous source of pride for a neighborhood—a project that can cost hundreds of millions of yen and involves the entire community in fundraising and support.

Beyond the Festival: The Unseen Calendar of the Daiku-gata

The festival’s explosive two days serve merely as the final exam. The true work—the deep, focused labor—takes place throughout the following 363 days. A `daikugata`’s life follows a seasonal rhythm, each season bringing its own tasks and pressures. The genuine heart of the craft is found in the quiet, dusty workshops scattered across Kishiwada.

The Autumn Aftermath: Assessment and Rest

Once the festival concludes in late September, a noticeable silence falls over Kishiwada. The danjiri, worn and battered, is carefully returned to its `danjiri-goya`, a specialized garage-like storage space. For the carpenters, there’s no time to rest—this is the moment of truth. Work starts almost at once with an exhaustive and meticulous inspection, akin to a post-battle damage assessment. The master carpenter, or `toryo`, and his team examine every inch of the float. They run their hands along massive beams, searching for invisible hairline cracks. Using small mallets, they tap joints to listen for any tonal shifts that might signal loosening within the structure. They crawl beneath, inspecting the chassis and the large wooden wheels for signs of strain. They climb to the roof to assess the intricate supports that endured the brunt of the `daikugata`’s dance. Every carved panel is gently cleaned and scrutinized for chips or new fractures. This slow, methodical process is undertaken with almost religious reverence. The `goya` is hushed, a stark contrast to the chaos of the festival, embodying deep concentration and respect for the wooden giant that has safely carried the community’s spirit another year. Any damage found is carefully recorded, creating a blueprint that will guide their work for the following eleven months.

Winter’s Embrace: The Deep Work Begins

With winter’s arrival from November through February, the real work commences. The `kouba`, or workshop, becomes the central hub for the `daikugata`. Outside, the air turns crisp, but inside the workshop, it is filled with the sharp, sweet aroma of Keyaki wood shavings and the focused energy of the craftsmen. This is the time for major repairs and, in rare special years, the monumental effort of crafting a new danjiri from scratch.

The Art of Repair: Healing the Wounds

Repairing a danjiri is unlike fixing ordinary furniture; it’s not a matter of wood filler and varnish. The principle is to preserve as much original material as possible. Each year adds character and history to the danjiri, and its aged wood is treasured. When a piece is beyond saving, the replacement process becomes an art. Carpenters must source Keyaki wood that matches not only in type but also in age, color, and grain. They maintain networks and secret caches of aged lumber reserved for this purpose. Since new wood expands and contracts differently than century-old timber, a perfect match is crucial. The damaged part is carefully removed by disassembling the `kumiki` joints, the brilliance of the design allowing the float to be taken apart like a complex puzzle. The new piece is then shaped with traditional hand tools. The hiss of a `kanna` (hand plane) shaving fine curls of wood and the rhythmic tap-tap-tap of a `nomi` (chisel) struck by a wooden mallet fill the workshop. Precision to fractions of a millimeter is vital—a joint too tight can crack under pressure, too loose and the entire structure loses integrity. This delicate balance of engineering and intuition requires a lifetime to master. The work demands immense physical strength guided by a feather-light touch.

The Birth of a New Legend: Crafting a New Danjiri

A `shinchou`, the creation of a brand-new danjiri, is a generational event rarely seen in a town. It is a multi-year, multi-million-dollar community endeavor. The process begins with selecting the wood—a sacred ritual in itself. The `toryo` travels to find perfect, ancient Keyaki trees, sometimes centuries old. Ceremonies bless the tree before felling it. After the raw timber arrives at the workshop, it is left to season for years to let moisture slowly escape, stabilizing the wood. The design merges ancient blueprints passed through generations with the unique vision of the current `toryo`, who holds the entire complex structure in his mind. Construction is a slow, deliberate symphony of labor. Massive beams are hand-shaped and planed; the intricate `kumiki` joints are cut with astonishing precision. The workshop buzzes with activity yet keeps an atmosphere of deep focus. The master works alongside apprentices, teaching through example rather than words alone. An apprentice may spend years simply sweeping floors and sharpening tools, learning to feel the wood and understand the rhythm before ever making a critical cut. This system rests on patience, respect, and the slow transmission of embodied knowledge. Witnessing them work is seeing a living tradition, a direct, unbroken lineage stretching back centuries.

Spring’s Awakening: Carvings and Community

As spring warms the air from March to May, the focus often shifts toward artistic detail. While structural carpenters continue, the `horimono-shi`—the master carvers—are deeply engaged in their craft. Their workshops are separate yet intimately connected to those of the `daikugata`. A carver’s studio is a world unto itself, where blocks of wood transform into scenes of epic drama. Hundreds of chisels and gouges in every size and shape line the walls. The carver studies historical texts and art scrolls for weeks before touching wood, immersing himself in the narrative he will carve. The carving is an act of immense patience; a single intricate panel can take over a year to finish. The carver must be both artist and engineer, understanding how wood grain will affect the final piece and how the sculpture will endure the festival’s violent motions. A continual dialogue exists between the `toryo` and the `horimono-shi`; carvings must integrate flawlessly with the danjiri’s structure—both aesthetically and functionally. This time also increases community involvement. Local leaders and members of the danjiri preservation association visit the workshop to track progress. The float is their shared treasure, inspiring pride and commitment. This connection sustains the carpenters, reminding them their work honors the spirit of the whole community.

Summer’s Heat: The Final Push

The heavy, humid summer heat from June to August signals the final, frantic phase before September. Pressure in the workshop mounts. This is assembly season. All repaired and newly crafted parts are gathered. The precision-cut `kumiki` joints are interlocked, a moment of intense focus. Even the slightest measurement error could weaken the whole structure. The `toryo` directs this process like a conductor with an orchestra, ensuring every piece fits perfectly. Once fully assembled, the final preparations start. Massive hundred-meter ropes are attached and brakes tested. Then comes one of the year’s most critical moments: the `tameshibiki`, or test pull. Weeks before the festival, the danjiri rolls out onto the streets for a practice run. For carpenters, this is nerve-wracking—the first real test of their year’s work against real-world forces. They watch intently, listening for strange creaks or groans and observing how the frame flexes on a turn. This final diagnostic trial precedes the main event. Seeing the danjiri in motion, hearing the townspeople cheer, witnessing their labor come alive—this is the reward making a year of sacrifice and painstaking effort worthwhile.

The Spirit of the Craftsman: A Legacy in Wood

Being a `daikugata` in Kishiwada is more than just a profession; it is a calling—a sacred trust passed down through generations. The culture surrounding this craft is as rich and intricate as the Keyaki wood they shape. It is a realm founded on apprenticeship, mastery, and a deep philosophy of creation.

The Role of the Toryo: Beyond a Carpenter

At the apex of this tradition stands the `toryo`, the master carpenter. He holds ultimate authority over every aspect of the danjiri’s construction and upkeep. The `toryo` is more than a skilled woodworker; he is an engineer, artist, historian, project manager, and community leader all in one. His knowledge is vast and encyclopedic—he knows the history of every danjiri in the city, the lineage of the carpenters who crafted them, and the distinct character of each float. Becoming a `toryo` is not a role one simply applies for; it is earned after decades of rigorous apprenticeship. A young boy may begin in the workshop, spending his early years observing, cleaning, and learning humility. He masters sharpening tools to a razor’s edge, a fundamental skill that imparts discipline and respect for the craft. Gradually, he is entrusted with small tasks, steadily gaining the master’s trust. This process can extend over twenty or thirty years. Much of the transmission of knowledge is non-verbal—apprentices learn by watching the master’s hands, sensing how he balances his body, and absorbing the rhythm of his work. This philosophy, known as `shokunin-damashii`, or the craftsman’s spirit, embodies a commitment to perfection for its own sake, along with a profound responsibility to the materials, tools, and community they serve. The `toryo` bears this responsibility daily, as the safety of hundreds during the festival depends entirely on the integrity of his work.

The Danjiri as a Living Being

Perhaps the most captivating aspect of this culture is how the carpenters perceive the danjiri itself. To them, it is not merely an object but a living entity with a soul, or `tamashii`. They speak of the danjiri as though it were a person, describing its ‘health,’ ‘mood,’ and ‘voice.’ Repairing a crack is seen as ‘healing a wound,’ and building a new one is regarded as overseeing a ‘birth.’ This belief permeates every action, explaining the extraordinary care and respect they give the wood. They are not simply assembling a machine but acting as caretakers of a powerful spiritual entity that embodies the collective spirit of their town. This outlook transforms the work from a task into a dialogue—the carpenter must listen to the wood, understand its strengths and limitations, and work with it rather than against it. As someone who spends days hiking and connecting with nature, this concept resonates deeply with me. It reflects a profound awareness that we exist in partnership with the natural world, whether traversing a forest trail or shaping a piece of timber in the workshop. This spiritual connection is the secret essence—the unseen force—that elevates a Kishiwada danjiri from a mere float into a true work of art.

Experiencing the Craftsmanship First-Hand

Reading about this is one thing, but experiencing it firsthand is quite another. While the inner sanctum of the `kouba` is a private realm of intense labor, there are opportunities for curious visitors to engage with this incredible tradition, both during the festival and in the quiet off-season months.

Practical Guide for the Curious Visitor

Getting to Kishiwada is easy from central Osaka. Simply take the Nankai Main Line from Namba Station. It’s a direct trip, taking about 30 minutes on an express train. The festival festivities are mainly focused around Kishiwada Castle and the nearby streets around the station.

Clearly, the best time to visit is during the festival, held on a weekend in mid-September. However, if you want to appreciate the craftsmanship without the huge crowds, I strongly suggest visiting during the off-season. This is when you can go to the Kishiwada Danjiri Kaikan, the city’s official danjiri museum. It’s located right next to the castle and is an absolute must-see. Inside, you can get close to a full-sized, historic danjiri. You can admire the carvings at your leisure, noticing details impossible to catch as they speed by during the festival. The museum offers fantastic exhibits explaining the construction process, the festival’s history, and the stories behind the carvings. Large screens show dynamic, multi-angle videos of the `yarimawashi`, giving you a vivid sense of the festival’s energy in a safe setting. It’s the ideal place to fully grasp the scale and artistry of these masterpieces.

Regarding the workshops themselves, these are not tourist attractions. They are active, and often hazardous, workplaces where carpenters follow tight schedules. Still, if you stroll through the older neighborhoods of Kishiwada, especially near the castle, keep your ears open. You might hear the rhythmic tapping of a hammer or the scraping of a plane on wood. You could glimpse through an open door to see a master at work—quiet moments of creation that form the foundation of the September roar. Just be respectful, observe from a distance, and cherish this rare glimpse into a hidden world.

Tips for Festival Day

If you choose to attend the festival—as I strongly recommend at least once—here are a few tips to enhance your experience. First and foremost: safety. This is serious. The danjiri move incredibly fast, and the crowds are enormous. The top rule is to follow instructions from the police and festival officials in uniform. Stay on the sidewalks and never, under any circumstances, try to cross a street when a danjiri is coming. Pick a spot to watch and stick to it, especially near the corners where the `yarimawashi` takes place. These moments are the most thrilling but also the most crowded. Arrive early to secure a good vantage point. The area around Kishiwada Station and the main ‘Kankanba’ intersection are popular, but my personal recommendation is to find a spot along a longer straightaway. There, you can feel the incredible speed and power of the pullers without the intense crowding of the corners. Wear comfortable shoes, bring water, and prepare for the noise. Embrace the chaos, grab some `takoyaki` from a street vendor, and let the vibrant energy of the city carry you away. It’s a raw, powerful, and uniquely Osakan experience you will never forget.

A Final Chisel Mark

The thunder of the Kishiwada Danjiri Matsuri is a fleeting phenomenon, a brilliant burst of sound and fury that shines intensely for two days before disappearing. Yet, the true spirit of the festival, its enduring soul, is not found in the chaos of the corner turn. It resides in the quiet, patient dedication of the `daikugata`. It lives in the scent of Keyaki wood shavings on a cold winter morning, in the gleam of a perfectly sharpened chisel, and in the passing of knowledge from a master’s hands to an apprentice’s eyes. The festival is the magnificent celebration, but the year-round labor is the prayer. It serves as a powerful reminder that the most spectacular cultural moments often rest on a foundation of quiet, unseen, and steadfast devotion. The next time you encounter something beautiful and skillfully crafted in Japan, whether a temple, a garden, or a simple bowl of ramen, take a moment to reflect. Consider the hands that created it, the years of practice, and the spirit infused within it. In a world that’s constantly rushing, the `daikugata` of Kishiwada remind us of the profound power in taking time, doing things right, and pouring your whole soul into the work of your hands. That is a tradition deserving celebration all year long.