Most people meet Kuromon Ichiba Market for the first time around noon. The air is thick with the scent of grilled scallops and sweet soy sauce, a chaotic symphony of sizzling, shouting, and the multilingual chatter of tourists navigating the packed arcade. It’s a feast for the senses, a vibrant, living postcard from Osaka, often dubbed ‘Osaka’s Kitchen’. My first few encounters were just like that—a wide-eyed wanderer from Down Under, clutching a stick of grilled octopus, marveling at the sheer energy of it all. But living here, you start to see the city’s rhythms in a different light. You learn that the brilliant, high-energy performance you see at midday is the grand finale of a show that started long before the sun came up, in the cold, quiet darkness of a sleeping city.

The real Kuromon, the one that powers the feast, wakes up when Namba’s neon signs have finally gone to bed. The true story of this market, and in many ways, the story of Osaka itself, isn’t found in the perfectly arranged trays of fatty tuna presented to tourists. It’s in the raw, unglamorous, and utterly essential hustle that happens between three and seven in the morning. It’s a world of ice-filled styrofoam boxes, the screech of metal shutters, and a language of commerce spoken in grunts, nods, and the city’s famously blunt dialect. To understand this pre-dawn ritual is to understand the engine of Osaka’s soul—a relentless work ethic fueled by pride, pragmatism, and a deeply personal connection to the craft of selling. This isn’t just about fish and pickles; it’s about the very DNA of a merchant city.

To truly grasp the soul of Osaka, one must also understand the distinct social dynamics of its neighborhoods, such as the unspoken code of Nishinari.

The 3 AM Alarm: More Than Just a Job

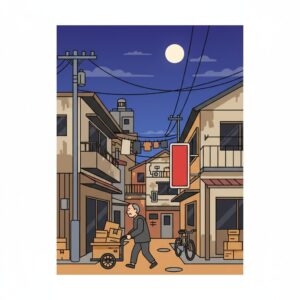

Long before the first commuter train rumbles beneath the city, a different kind of traffic stirs in the narrow streets around Kuromon. It is a procession of small, refrigerated trucks and boxy K-vans, their headlights piercing the pre-dawn gloom. They move with quiet purpose, parking in spaces that seem impossibly tight, their drivers stepping out not with the grogginess of a reluctant start, but with the focused energy of those ready to tackle a mountain of work before most of the city even thinks about hitting the snooze button. This is the 3:30 AM pulse of Kuromon, where the day truly begins.

The Silent Commute and the First Light

At this hour, the air carries a different scent. It is clean, cold, and tinged with the faint, briny smell of the sea—a promise of the cargo unloaded from the central wholesale market. The usual cacophony of Osaka is replaced by a more mechanical soundtrack: the low hum of refrigeration units, the metallic clang of a security shutter rolling up, the squeak of dolly wheels on wet pavement. Inside the arcade, the first lights flicker on, casting long shadows down the covered street. It is a skeletal version of the market, stripped of its daytime vibrancy and revealing the bare bones of commerce.

This is the hour of the masters—the third- and fourth-generation shop owners who inherited not just a business but a way of life. Take someone like Hashimoto-san, whose family has run a fugu (pufferfish) shop here since before the war. His alarm never goes off at 3 AM; his body simply knows. The commute is a short drive or bike ride through a ghost-town version of the city he serves. This isn’t the soul-crushing, jam-packed commute of a Tokyo salaryman headed to a skyscraper in Marunouchi. It’s a solitary journey to a place bearing his family name. His mindset isn’t about clocking in for a corporation; it’s about opening the doors to his own legacy. This distinction is key to understanding Osaka. Here, business, or shoubai, is deeply personal. Pride lies not in the corporate brand you work for, but in the name etched on your own noren, the traditional curtain hanging over your shopfront.

The Ritual of Preparation

Once the shutters are up, the ritual begins—a dance of preparation honed over decades into raw efficiency. For the fishmongers, the first task is ice. Mountains of it. Huge bags of crushed ice are hauled from delivery trucks and shoveled into display cases, creating the cold foundation that will preserve the day’s catch. The sound of ice scraping against stainless steel is the market’s first true heartbeat.

Then come the knives. The array of blades wielded by a single fishmonger is an art in itself—long, slender yanagiba for slicing sashimi, heavy, cleaver-like deba for breaking down whole fish. Sharpening is a meditative ritual, a moment of quiet focus before the coming storm of activity. Water trickles over a whetstone as the blade is drawn across it with a soft, rhythmic shhh-shhh-shhh. This is the sound of a shokunin, a craftsman, tuning his instrument. The precision is more than just display; it’s a sign of respect for the product. In Osaka, wasting good food is the highest sin, and a clean, sharp cut from a well-honed knife ensures every part of a valuable fish is treated with care.

At the vegetable stalls, the work is equally meticulous. Boxes of produce are unpacked, and each radish, cucumber, and bundle of greens inspected. Arranging the display is an art form—not merely piling things high, but creating a landscape of color and freshness: the vibrant green of spinach beside the deep purple of eggplant, the fiery red of a tomato next to the pale white of a daikon radish. This isn’t shelf-stocking; it’s stage-setting. The performance begins long before the audience arrives.

The Language of the Market: A Symphony of Commerce

As more vendors arrive and the pace quickens, the silence gradually gives way to the authentic language of Kuromon. This is a dialect of commerce that can be daunting to outsiders. It’s loud, rapid, and layered with meanings far beyond the literal words. To someone unfamiliar, especially those used to Tokyo’s quiet, formal tones, it might sound like a series of heated arguments. Yet, listen carefully, and you’ll catch the rhythm of relationships being formed and maintained—a verbal shorthand for a community built on trust and mutual understanding.

“Maido!” and the Art of Greeting

The most important word in the Kuromon vocabulary is “Maido!” (まいど!). It rings out through the arcade from the moment the first vendors greet each other. A delivery driver dropping off a box of styrofoam containers receives a hearty “Maido!” The fishmonger waves to the pickle vendor across the way with a “Maido!” Literally, it is a contraction of “maido arigato gozaimasu,” meaning “thank you for your continued patronage.” But in everyday use, it’s much more: a greeting, a thank you, a “how’s it going?,” and a “see you later,” all rolled into one. It serves as the social glue for Osaka’s merchant community, continually emphasizing that every transaction is part of an ongoing relationship, not a one-time exchange.

The banter that follows is pure Osaka. It’s filled with teasing, inside jokes, and a bluntness that can be surprising. You might hear one shop owner shout to another, “You’re charging that much for those cucumbers today? Are you crazy?” This is not an insult but a form of engagement—a way to gauge the market, share information, and maintain a competitive yet friendly spirit. In Tokyo, such directness might be considered rude or confrontational; in Osaka, it’s just business as usual. The absence of pretense is refreshing, reflecting a culture that values honesty—even blunt honesty—over polite vagueness. The aim is to get straight to the point, share a laugh, and get back to work.

The Unspoken Rules of Negotiation

This frankness carries over to customer interactions but is governed by unspoken rules that foreigners often misinterpret. The ideas of nebiki (price reduction) and omake (a little something extra) are central to the Osaka shopping experience. Tourists sometimes come expecting to haggle aggressively, as in other markets worldwide. This is a mistake. Negotiation at Kuromon is a subtle dance, not a confrontation.

You don’t demand a discount; instead, you build rapport. You ask the vendor, “Ochian, what’s good today?” and show genuine interest. If you become a familiar face, the relationship changes. One day, after buying three pieces of fish, the vendor might weigh them, check the price, and say, “Okay, for you, this much,” knocking a hundred yen off without you asking. That’s nebiki. It’s a reward for loyalty.

Even more common is the practice of omake. You buy a bag of pickled daikon, and as the shopkeeper hands it to you, she might toss in some extra slices of pickled ginger. “This is a service,” she’ll say with a smile. That little extra isn’t about money; it’s a gesture of goodwill—a way of saying, “I see you, I appreciate you, please come again.” This is the brilliance of Osaka commerce. It recognizes that human connection is the best marketing tool. A fixed-price, impersonal transaction in a Tokyo department store may be efficient, but it fosters no bond. Osaka’s omake culture builds relationships that can last for generations.

Generations of Grit: The Family Business Model

Many of the stalls in Kuromon are more than just shops; they are miniature dynasties. The faces you see expertly slicing tuna or arranging strawberries often belong to the third, fourth, or even fifth generation working in the same spot. This deeply rooted family tradition forms the backbone of the market’s resilience and offers a powerful insight into the Osaka mindset. The work is not merely a means of earning a living; it is a duty to one’s ancestors and a legacy to be handed down to future generations.

The Significance of a Noren

Hanging at the entrance of each established shop is a noren, a traditional fabric divider. More than a mere sign, the noren bears the family name or crest and symbolizes the entire history and reputation of the business. To work beneath that noren is to shoulder the weight of generations of tireless effort. It is a source of great pride but also heavy pressure. This stands in stark contrast to the anonymity of corporate life.

Picture a young man in his late twenties who now runs his family’s tsukemono (pickle) shop. His grandfather created the recipe for their famous pickled eggplant, a secret passed down to his father and now to him. He could have chosen a different path, perhaps an office job in Umeda, but instead, he embraced the family business. His day begins at 4 AM, stirring massive vats of brine, his hands raw from the salt and cold. He does this because the shop is more than a collection of assets; it embodies his family’s identity. His success or failure directly reflects on the family name. This profound sense of responsibility inspires a remarkable work ethic. He isn’t working for distant shareholders; he’s ensuring his grandfather’s legacy endures. This is the grit defining so many of Osaka’s small business owners—they are resilient, resourceful, and fiercely independent because they must be.

From Grandfather’s Knife to Son’s Smartphone

While tradition is deeply respected, Osaka is fundamentally a city of pragmatists. Though Kuromon vendors may rely on their grandfather’s pickling recipe, they are far from stuck in the past. They have a remarkable ability to adapt—an attribute cultivated over centuries of navigating the unpredictable waves of commerce. If a new method or technology helps sell more products, they adopt it without hesitation. This pragmatic mindset sets them apart from other, more tradition-anchored regions of Japan.

Strolling through the market today, you see this fusion of old and new everywhere. The elderly dried-goods shop owner, who probably has used the same abacus for fifty years, may have his grandson beside him managing the shop’s Instagram account, posting artful images of premium shiitake mushrooms and kombu seaweed. The tuna stall, carving fish the same way for over a century, now accepts multiple forms of digital payment via QR codes taped to the counter. Recognizing the influx of tourists, instead of grumbling about the crowds, they adapted. They began selling single servings of high-end otoro tuna on small trays for immediate consumption and started vacuum-sealing fish packs for travelers to take home. They are not sentimental about tradition if it hinders shoubai (business). The goal is to survive and prosper. This practical, unsentimental business approach embodies the spirit of Osaka—it’s all about what works right now.

Beyond the Tuna: The Ecosystem of Support

The market tourists witness is the front stage—a polished performance where individual stalls vie for their attention. Yet, the true magic of Kuromon, the vital force behind its operation, lies in the intricate, interconnected ecosystem thriving in its back alleys and during the pre-dawn hours. This network of suppliers, delivery personnel, and neighboring businesses functions less like competitors and more like a single, sprawling organism. Built on relationships often spanning decades, it is sustained by nothing more than a nod and a shared understanding.

The Wholesalers and Delivery Personnel

The fish, produce, and meat sold at Kuromon don’t simply appear by chance. In the early morning’s darkest hours, a steady flow of small trucks and scooters courses through the surrounding streets. These middlemen, delivery drivers, and wholesalers form an essential link in the supply chain. A Kuromon vendor’s relationship with his tuna supplier might trace back to his grandfather’s era. There are no elaborate written contracts; the vendor calls the wholesaler the night before and says, “I need a good bluefin, around 80 kilos. Make sure it’s a good one.” He relies on the wholesaler to select the best fish at the central market auction. Prices are settled with a few brief words. Delivery arrives at 4 AM. Payment may be made weekly or monthly, logged simply in a ledger. This system operates almost entirely on trust and reputation. In the fast-paced, cutthroat fresh food world, a person’s word is their most valuable currency.

This spirit of community extends among the vendors as well. The tempura shop buys shrimp from the fishmonger three stalls down. The fruit stand owner keeps a tab at the coffee shop at arcade’s end. When a vendor runs short of change, he doesn’t visit a bank; he calls to a neighbor, who tosses him a roll of 100-yen coins. There is a profound understanding that they are all in this together. Their fortunes are intertwined. A busy market day benefits everyone. This contrasts with the more isolated, competitive business environments in other cities. At Kuromon, a neighbor’s success is, in a small way, your own.

The Staff Meal: Fueling the Hustle

By around 6 AM, as the initial rush of setup begins to ease, a new scent drifts through the arcade—the aroma of makanai, the staff meal. This reveals another unvarnished reality behind the scenes. The food is simple, practical, and meant to provide sustenance. Often made from the day’s leftovers or slightly imperfect produce, the fishmonger’s staff may gather around a makeshift table in the stall’s back to eat bowls of rice topped with fish scraps from the previous day, simmered in a savory broth. The vegetable vendor might have a plain miso soup filled with daikon and carrot trimmings.

There’s a beautiful humility in the makanai. Surrounded by some of the country’s most luxurious and costly foods—premium Kobe beef, rare sea urchin, exquisitely marbled tuna—the vendors’ own breakfasts teach frugality. This embodies a classic Osaka trait known as shimat-su (始末), roughly meaning a blend of thriftiness and resourcefulness. It’s not about being cheap; it’s about avoiding waste and honoring resources. Why consume the expensive products meant for sale when a perfectly tasty meal can be made from the leftovers? The focus remains on the customer and the business. Luxury is for the clientele; for the staff, simple, hearty fuel is enough to sustain them through the long day ahead.

What Tourists See vs. What Residents Know

By 9 AM, the transformation is complete. The concrete floors have been sprayed down and swept clean. The last of the empty boxes have been swiftly removed. Every piece of fish gleams under bright lights, and every strawberry is perfectly arranged in its plastic container. The vendors, who just hours before were hauling ice and gutting fish in rubber boots and aprons, have changed into fresh uniforms, their faces bright with a welcoming, energetic smile. The curtain rises, and the performance for the public begins. This is the Kuromon everyone recognizes, but for those aware of what preceded it, the scene looks entirely different.

The Polished Performance vs. The Sweaty Reality

The daytime Kuromon is a carefully crafted piece of theater. The loud calls of “Irasshaimase!” (Welcome!), the dramatic displays of a whole tuna being carved, the friendly banter with customers—it’s all part of the act. And it is a remarkable show. But it’s important to realize that it is, indeed, a performance, born from hours of grueling, unseen labor. The effortless way a vendor slices a piece of sashimi is the product of tens of thousands of hours of practice that began in the early morning darkness. The bright, cheerful demeanor is kept up by people who have been on their feet since 3 AM.

For a local, this insight changes the way you engage with the market. You come to appreciate the hustle in a new light. You notice the subtle lines of fatigue around a shopkeeper’s eyes and feel a deeper respect for their energy. You understand that the price of that perfectly grilled scallop covers not only the cost of the shellfish, but also the expense of the early morning trip to the wholesale market, the hours of cleaning and preparation, and the sheer physical effort needed to keep the show running, day after day. What might seem to a tourist like a charming, chaotic market, a resident sees as a marvel of logistics and human endurance.

Misunderstanding Osaka “Friendliness”

This brings us to one of the most common clichés about Osaka: “Osaka people are so friendly!” While true on the surface, this observation often overlooks the deeper cultural context. The friendliness of a Kuromon vendor isn’t just an innate personality trait; it’s a professional skill, refined over generations of commerce. It’s a practical friendliness.

The obachan (auntie) at the pickle stall who insists you try a sample isn’t simply being kind. She’s opening a conversation, creating a small sense of obligation, and using a proven sales technique. The butcher who jokes with you about the weather is building a rapport he hopes will make you a loyal customer. This doesn’t make the friendliness fake or insincere. On the contrary, it’s an authentic part of the culture. But its roots lie in the realities of shoubai. In a city of merchants, your livelihood depends on your ability to connect with people, to make them feel welcome, to turn a stranger into a regular.

This sharply contrasts with the service culture in Tokyo, which is often defined by extreme politeness, formality, and a certain professional distance. The Tokyo style is flawless but rarely encourages personal connection. The Osaka style is messier, louder, and more direct. It invites you to engage, to banter, to become part of the scene. Understanding that this friendliness is a trade tool doesn’t lessen it; it enhances your appreciation for the sophisticated social intelligence behind it.

The Soul of the City in a Covered Arcade

When you combine all the elements—the pre-dawn labor, the personal pride of a family-run business, the practical acceptance of innovation, and the loud, relationship-centered trade—you get more than just a market. You get a microcosm of Osaka itself. Kuromon Ichiba is the city’s heart, its early morning rhythm pumping life through the entire metropolis. The values and work ethic showcased in this single arcade are the same ones that have shaped Osaka for centuries.

Why Kuromon Couldn’t Exist in Tokyo

It’s difficult to picture a place exactly like Kuromon flourishing in the center of Tokyo. The raw, unfiltered energy, the boisterous bargaining, the unapologetic focus on the deal—it’s all intrinsically Osaka. In Tokyo, a market of this significance might appear more curated, more orderly, perhaps more visually polished. The noise would likely be subdued, the exchanges more formal. The vibrant, functional disorder of Kuromon—the melting ice, the slightly chaotic stalls, the vendors shouting across aisles—might be viewed as something to control and sanitize.

But in Osaka, that chaos is essential. It’s the visible and audible expression of a city that has always valued substance over style, outcomes over procedure. Osaka was founded by merchants, not samurai or bureaucrats. Its heroes are those who can close a sale, earn a profit, and build a lasting enterprise. The etiquette here is different. A good bargain and a hearty laugh hold more worth than a perfectly performed bow. Kuromon embodies that spirit in every way.

The Enduring Resonance of the Morning Rush

Next time you stroll through Kuromon Ichiba at lunchtime, surrounded by the joyful clamor of tourists enjoying takoyaki and sea urchin, pause for a moment to listen. Beneath the bustle, you might catch the echo of the morning rush. It’s in the slightly raspy voice of the man selling grilled eel, a voice honed since 5 AM. It’s visible in the swift, efficient motions of the woman packing your strawberries, muscle memory forged through thousands of quiet morning hours. It’s found in the quiet confidence of the vendors, a calm born from having already completed a full day’s work before most customers have even started their first meeting.

This unseen early-morning effort is the foundation on which Osaka’s renowned food culture, nightlife, and dynamic economy rest. The city’s limitless energy is no secret; it directly stems from the thousands who rise in the darkness to sharpen knives, haul ice, and prepare the day’s feast. To live in Osaka and truly understand it is to recognize that the most thrilling part of the spectacle occurs long before the audience arrives.