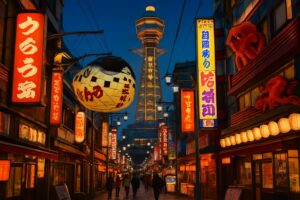

The first time you try to conquer Tenjinbashisuji Shopping Street, it conquers you. It’s a dizzying, relentless, 2.6-kilometer assault on the senses. You think you’re prepared. You’ve seen long streets before. But this isn’t just a street. It’s a living organism, a covered artery pulsing with the raw, unfiltered heartbeat of Osaka. The air is thick with the sweet-savory smoke of grilling eel, the sharp tang of pickled vegetables, and the comforting scent of fried croquettes. The noise is a symphony of chaos: the frantic clatter of pachinko parlors, the rhythmic shouts of vendors hawking their wares—“Yasui de! Otokuyo!”—the cheerful jingle of a supermarket checkout, and the incessant, polite-yet-menacing chime of bicycle bells demanding passage.

For a newcomer, especially one coming from the polished, curated politeness of Tokyo, it can feel like a system overload. It’s too much, too loud, too… messy. Tourists walk through it, snapping photos of the colorful banners and grabbing a quick takoyaki, treating it like an attraction. A very, very long attraction. But they’re missing the point entirely. Tenjinbashisuji isn’t a place you visit. It’s a place you use. This isn’t a theme park of old Japan; it’s the city’s communal pantry, its kitchen, its sprawling, chaotic living room where the real business of daily life gets done. To understand how thousands of Osakans navigate this arcade every day isn’t just to learn how to shop; it’s to learn the unwritten social contract of the city itself. It’s where you see the famous Osaka pragmatism, its obsession with value, and its surprisingly intimate sense of community in action. This is the decoder ring for understanding what makes Osaka tick.

To truly grasp how this daily rhythm translates into tangible value, consider exploring how Tenjinbashisuji serves as a practical solution for Osaka’s cost of living.

It’s Not a Mall, It’s a Ecosystem

Before we explore the how, we first need to grasp the what. A shotengai, or shopping arcade, is fundamentally unlike a modern American-style mall. A mall is a controlled environment, a single entity crafted for a smooth, branded consumer experience. Everything is tidy, climate-controlled, and predictable. The music is carefully selected, storefronts are uniform, and interactions are transactional, guided by corporate training manuals.

Tenjinbashisuji is the exact opposite. It’s a chaotic alliance of independent businesses, a living history of commerce. It developed organically, a collection of personal dreams and livelihoods nestled together under one roof for shelter from Osaka’s harsh summer sun and sudden rainstorms. There’s no central management imposing an aesthetic. A tiny, generations-old knife-sharpening stall, its wood worn smooth by a century of use, might sit right next to a brightly lit drugstore chain blasting J-pop. A quiet, elegant kimono shop shares a wall with a greasy spoon serving cheap and delicious curry rice. This striking contrast isn’t a flaw in design; it’s the essence of the place. It mirrors the city’s character: unpretentious, diverse, and fiercely independent.

The covered roof is more than just functional; it creates a psychological space. It transforms a public street into a semi-private corridor. Life unfolds here, openly. You’ll see shopkeepers eating lunch on stools outside their shops, children doing homework in the back of the family fruit stand, and elderly neighbors pulling up chairs to gossip for hours. It’s a third space, neither home nor work, fostering a casual intimacy you’ll never find in the sterile hallways of a shopping mall. This is the fundamental difference: a mall is for consumers, but a shotengai is for residents.

The Rhythm of the Arcade: A Day in the Life

To truly understand Tenjinbashisuji’s significance, you need to witness it as it flows through its daily rhythms. The arcade possesses a unique pulse that shifts with the hours, each phase unveiling a different aspect of Osaka life.

Morning: Seeking Freshness and Familiarity

The day doesn’t start with a bang but with a rumble. Around 9 AM, the metal shutters of hundreds of shops begin their noisy rise, their echoes rolling down the long arcade like a wave. This hour belongs to the pros: elderly locals, equipped with their small wheeled carts, or koro-koro, as they’re fondly called. They are the custodians of quality, the living archives of the arcade’s best bargains.

They move with slow, deliberate intent. This is no casual stroll but a mission. They’re not merely purchasing groceries; they’re selecting their meals with care. They pause at their favorite fishmonger, not just to buy a piece of mackerel, but to inquire about the best catch of the day. The exchange is a quick-fire conversation in thick Kansai dialect. “O-chan, kono saba, yakeru no ni é ka?” (Hey, is this mackerel good for grilling?). The fishmonger, wiping his hands on his apron, replies with a candid, straightforward opinion. “Ah, kocchi no aji no hou ga abura notte umいで” (Nah, this horse mackerel is fattier and tastier today). This isn’t upselling—it’s a relationship built on years of trust. He knows her preferences, and she relies on his judgment. Buying the wrong fish would be a minor breach of that bond.

The air is rich with the fresh, earthy scent of daikon radishes stacked high and the yeasty smell from small, independent bakeries. The greengrocers, with their chaotic, overflowing displays, are a crucial battleground. Here, price is only part of the story. The obachan picks up a tomato, turning it over in her hand, examining it with the scrutiny of a diamond appraiser. She checks for firmness, color, and the subtle aroma that signals peak ripeness. This tactile, sensory connection to food is worlds apart from the plastic-wrapped perfection typical of Tokyo supermarkets. In Osaka, you trust your own senses first and the vendor’s relationship second.

Midday: The Lunch Rush and the Art of Eating Fast

As noon nears, the crowd changes. The leisurely pace of the morning shoppers gives way to the bustling energy of the lunch rush. Office workers, nearby students, and shopkeepers on break flood the arcade, seeking something quick, affordable, and satisfying. This is where Osaka’s reputation for kuidaore—eating until you drop—is made accessible. It’s not about pricey gourmet meals but about maximizing flavor and fullness with minimal yen.

The lines tell it all. A queue of a dozen people stretching out of a tiny stall isn’t a nuisance; it’s a glowing endorsement. It means that the 80-yen croquette, 300-yen bowl of udon, or freshly fried tempura is worth waiting for. Osaka people have an almost uncanny skill in spotting good kosupa (cost performance). They will happily wait ten minutes to save 50 yen and get a superior product.

This is the world of tachigui (standing-and-eating) and tachinomi (standing-and-drinking). Space and time are precious. You’ll see salarymen in suits hunched over tiny counters, slurping soba in under five minutes. There’s no pretense or small talk; it’s a purely functional refueling act that still demands quality. The broth must be flavorful, the noodles perfectly chewy. Efficiency doesn’t mean mediocrity. This pragmatic dining approach is quintessentially Osaka. Why waste time and money on a fancy seat when the food itself is the real point?

Afternoon: A Slower Pace, A Social Atmosphere

After the lunchtime rush fades, a deceptive calm settles over the arcade around 2 PM. This is when the shotengai’s social role takes center stage. The pace slows, the frantic energy subsides, and the street reverts to a neighborhood thoroughfare. This time is for errands that blend connection with consumption.

You’ll see mothers with small children stopping to chat with the kimono shop owner they’ve known since childhood. Elderly men gather at a traditional tea shop, not just to buy sencha but to sit on the bench, sip a sample cup, and discuss the world’s problems with the proprietor. These shops are more than retail—they’re vital community hubs, informal daytime gathering spots.

This is when the small details stand out: the pharmacy with a blood pressure cuff outside for anyone to use freely, the butcher nodding warmly to every familiar face, the bookstore owner who knows which customers await the latest mystery novel release. This web of micro-interactions is the glue binding the community. It sharply contrasts with the impersonal, transactional nature of big-city life so common in Tokyo. Here, you’re not a customer number—you are Tanaka-san’s daughter or Suzuki-san from the third floor. Your identity is woven into the arcade’s fabric.

Evening: The Rush to Get Dinner Ready

Around 5 PM, the final daily transformation occurs. The arcade fills again, this time with people heading home from work. Their goal is clear: get dinner on the table. The Osaka approach is a masterclass in efficiency and culinary strategy. The aim is a home-cooked meal without spending hours cooking after a long day.

This is prime time for the osozai-ya, shops offering a stunning variety of pre-made side dishes. Gleaming trays brim with simmered pumpkin, savory fried karaage, delicate tamagoyaki (rolled omelets), and a dozen types of salads. People don’t buy a full ready meal but assemble one. They’ll cook rice at home, maybe prepare a simple miso soup, then complement it with two or three expertly prepared dishes. It’s the perfect balance between a fully home-cooked meal and a takeaway bento. Practical, economical, and still personal.

Supermarkets inside the arcade, like the famous Super Tamade with its neon lights and incredibly low prices, become battlegrounds. This is when time-based discounts—waribiki—come into play. Shoppers circle the sushi and sashimi sections like sharks, waiting for staff to apply coveted 20%, 30%, or even 50% off stickers. Once the stickers go on, a polite but determined rush ensues. This well-practiced dance isn’t about poverty but the joy of getting a good deal. Paying full price for something that will be half-off soon is, to Osaka minds, simply illogical.

The Osaka Code: How to Shop Like You Belong Here

Navigating Tenjinbashisuji successfully requires familiarity with a set of unspoken rules and cultural subtleties. It’s a language conveyed not only through words but also through gestures, expectations, and a shared philosophy of value. Mastering this code is essential for experiencing the true spirit of Osaka.

The Price is a Conversation Starter, Not a Conclusion

Let’s tackle the big topic: haggling, or negiro. The common stereotype is that everyone in Osaka bargains over everything. This is a misleading oversimplification. Try to haggle at a 7-Eleven or a major department store, and you’ll likely receive confused silence. The art of negiro is subtle and depends heavily on context.

It occurs almost exclusively at small, independently owned stalls—the fruit vendor, the fishmonger, the tiny shop selling dried goods. It’s not about aggressively lowballing prices either. Rather, it’s a playful, conversational dance. It often starts when buying multiple items. You might pick up a bag of oranges, a bunch of bananas, and a melon. As the owner calculates the total, you might smile warmly and say, “Chotto makete kureru?” (Could you give me a little discount?). Or more slyly, “Kore, zenbu de sen-en ni naran?” (Can this all come to an even 1,000 yen?).

The shopkeeper will likely laugh, perhaps suck air through their teeth in mock consideration, then either offer a small discount or, more commonly, add something extra to your bag—a practice called omake. “Shikata nai naa, kore omake shitaru wa!” (Can’t help it, I’ll give you this as a bonus!). You might receive an extra orange or a slightly bruised but still edible apple. The goal isn’t just to save 50 yen but to enjoy the interaction. It’s a little game that confirms your status as a savvy, regular customer and their role as a generous, friendly merchant. This strengthens the relationship. Whereas in Tokyo, the price is a fixed, impersonal fact, in Osaka, it can be the start of a human connection.

“Maido!” is More Than Just a Greeting

Words carry weight here, and the local dialect, Kansai-ben, serves as the official language of commerce in the arcade. The most important word to know is “Maido!” Literally, it means “every time,” but its real significance is “Thank you for your continued patronage.” It’s both a greeting and a thank-you combined, expressing an ongoing relationship. When a shopkeeper greets you with “Maido!,” they’re not just welcoming you; they’re recognizing you as a regular, a member of the community. Hearing it from your local butcher for the first time feels like leveling up in the game of Osaka life.

There’s also the classic merchant’s call-and-response. One shopkeeper might greet another with “Mokari makka?” (Making money?). The usual, almost obligatory reply is a wry smile and “Bochi bochi denna” (So-so, just getting by). No one, regardless of success, would boast about thriving business. It’s a display of humility and camaraderie, an acknowledgment that everyone is in the same boat and working hard. This linguistic ritual offers a glimpse into the soul of Osaka’s akindo (merchant) culture, which values diligence, modesty, and shared struggle.

Look for the Lines, Trust the Crowd

In many cities, a long line might be a deterrent. In Osaka, it’s an attraction. The local mindset relies on a strong principle of social proof. If many people are willing to wait, the product must be exceptional for its price. The most famous example is Nakamura-ya, a small stall selling 80-yen croquettes. There’s almost always a line, and for good reason. Their croquettes are crispy, fluffy, and unbelievably cheap. An Osaka local would see that line and think, “That’s the one,” not “I don’t have time for this.”

This trust in the crowd’s judgment extends beyond food. You’ll notice it at a tissue vendor offering a special deal, at the sock shop selling three pairs for a bargain, or at the fishmonger when a particularly good catch arrives. People stop, spot a crowd gathering, and join in, trusting their fellow citizens have uncovered a deal worth seizing. It’s communal bargain-hunting, a collective intelligence aimed at finding the best value. This creates a lively, dynamic environment where hotspots of activity can appear and disappear within minutes.

The Unspoken Rules of a Crowded Road

Moving through the physical space of Tenjinbashisuji demands a type of urban fluency. What seems like chaos is actually governed by an unspoken order.

The Bicycle Menace and the Pedestrian Dance

Technically, bicycles are supposed to be pushed through the arcade, a rule widely known but almost universally ignored. Bikes dart through dense crowds with startling precision. As a pedestrian, you develop a sixth sense. You avoid sudden moves. You hold your bags close. You listen for the familiar ring-ring of a bell, which is less a polite warning and more a statement of fact: “I am coming through.” It’s a delicate, high-stakes ballet. Visitors freeze or leap aside, while locals subtly form a narrow, temporary channel in the crowd, flowing around the bike like water around a rock, then closing ranks again immediately. It’s a marvel of unconscious, collective coordination.

The Art of the Sudden Stop

With so much to see, the temptation to stop abruptly is strong. Doing so improperly is a cardinal sin. It can cause a domino effect and earn sharp glares. The local method is to signal your intent. Gradually slow down, drift toward the edge of the main pedestrian flow, and only then stop, huddling close to the storefront. This creates a small eddy, allowing the main stream of people to pass by smoothly. It’s about spatial awareness and respect for the collective flow.

The Faces of the Arcade: Merchants and Shoppers

Ultimately, Tenjinbashisuji is a story about people. The arcade serves as a stage, with merchants and shoppers as its lifelong performers, enacting the daily drama of commerce and community.

The Legacy Merchants: Keepers of Tradition

Venture deep into the arcade, beyond the bright chain stores near the station entrances, and you’ll discover the legacy shops. These are businesses handed down through three, four, or even five generations. The man selling konbu (kelp) from a large wooden storefront isn’t merely retailing seaweed; he is a curator of dashi, the essential flavor of Japanese cuisine. He can explain which type of konbu suits a clear soup best and which is ideal for a hearty stew. His knowledge was inherited from his father, who received it from his grandfather. His shop is a repository of flavor, and he is its chief librarian.

Further along the street, the knife-maker bends over a grinding wheel, sending sparks flying into the air. His hands are calloused yet steady. He can examine your dull kitchen knife and recount its life story. He sharpens it with a reverence that borders on spiritual, transforming it from a blunt tool into one of precision. These merchants sell more than just products; they are guardians of a craft, living links to Osaka’s past. Beneath their gruff exteriors lies a profound pride in their work and a readiness to share their expertise with anyone genuinely interested.

The Savvy Shoppers: Experts in Bargains

The shoppers are equally vital to the arcade’s character. Chief among them is the iconic Osaka obachan. She is a force of nature. Armed with her wheeled cart, sun visor, and encyclopedic knowledge of market prices, she is the ultimate consumer. She knows the daikon radishes in the shop at 3-chome are ten yen cheaper than those at 4-chome, but the ones in 4-chome are fresher on Tuesdays. She moves through the arcade with an efficiency that would impress even a military strategist.

She isn’t afraid to voice her opinion. She’ll inspect a fish, judge it not fresh enough, and walk away. Yet, she is fiercely loyal. Vendors who consistently provide quality goods at fair prices earn her business for life. She is the driving force of the arcade’s economy, the enforcer of its unwritten rules of quality and value. Watching her operate is a masterclass in practical, no-nonsense living.

Why Tenjinbashisuji is the Anti-Tokyo

The deepest insights into Tenjinbashisuji, and by extension Osaka, emerge when contrasted with its eastern counterpart, Tokyo. The two cities embody distinct philosophies of urban life, commerce, and culture, a contrast vividly reflected in their respective shopping atmospheres.

Function Over Form: The Charm of Simplicity

Step into a boutique in Tokyo’s Omotesando, where the space is likely minimalist, featuring carefully designed lighting, polished concrete floors, and a single flawless product displayed like an artwork. The presentation is paramount, conveying a refined, aspirational perfection. Now, step into a fruit stand in Tenjinbashisuji, where the scene is a colorful, chaotic burst of cardboard and handwritten signs boldly marking the day’s prices. Boxes are piled high, with produce spilling out. By Tokyo standards, it’s disorderly. Yet, to the Osaka eye, it’s beautiful. This apparent mess signifies abundance, freshness, and low overhead. Rather than spending on decor, savings are passed to customers through lower prices. Osaka’s aesthetic philosophy, kazaranai, values the essence of the item rather than its packaging. A perfectly tasty tomato in a worn cardboard box outweighs a mediocre tomato in an elegant display.

Directness vs. Delicacy: Contrasting Styles of Service

Tokyo’s service is a refined art of politeness—formal, deferential, and precisely choreographed, marked by deep bows, honorific language, and careful distance between customer and staff. In contrast, service in Tenjinbashisuji is conversational—direct, familiar, and refreshingly candid. A Tokyo shopkeeper would never discourage a purchase, but an Osaka vendor might. For instance, if you pick up a melon that’s not quite ripe, they might say, “Anchan, sore mada hayai de. Kocchi no hou ga tabegoro ya” (Hey buddy, that one’s still early. This one here is ready to eat). This is not rudeness, but profound respect—they value both your money and palate enough to steer you away from an inferior choice. They’re not merely service providers; they’re partners in your pursuit of quality food. While this bluntness may surprise outsiders, understanding its sincere intent—to offer the best value—makes it a treasured form of communication.

A Community, Not Just Consumers

Perhaps the most striking difference is in the sense of community. While Tokyo boasts charming neighborhoods, its major commercial hubs exude respectful anonymity, where you are one among millions—a consumer navigating an efficient yet impersonal system. Tenjinbashisuji, despite its vast size, operates like a small town. The dense human interactions—haggling, greetings, waiting in line together—foster a rare level of engagement in a modern city. Shopkeepers watch their customers’ children grow, and shoppers know the names of those who sell their rice. This web of weak social ties forms a safety net and a profound sense of belonging. Shopping in Tenjinbashisuji is not just a transaction; it’s participation in a centuries-old story. In doing so, you become more than an Osaka resident; you become part of its vibrant, pragmatic, and deeply human spirit.