Forget the hushed temples and manicured gardens for a moment. Forget the sleek, futuristic face of Japan you see in magazines. I want to take you somewhere real, somewhere with a bit of grit under its fingernails and a whole lot of heart beating under its neon skin. We’re going to Kyobashi, a district in Osaka that serves as a thrumming, electric crossroads for the city’s working soul. This isn’t a place designed for tourists; it’s a place designed for living, for unwinding, for celebrating the end of another long day with a cold beer and something hot, crispy, and utterly delicious. We’re diving headfirst into the world of tachinomi, or standing bars, on a quest for the perfect kushikatsu—Osaka’s signature deep-fried skewers. Here, in the narrow alleys and covered shopping arcades radiating from the bustling train station, you’ll find the city’s authentic, unfiltered flavor. It’s a world of sizzling fryers, clinking glasses, and the warm, welcoming chatter of locals. This is where you don’t just eat Osaka; you experience it on your feet, one golden skewer at a time.

The Electric Heartbeat of Kyobashi

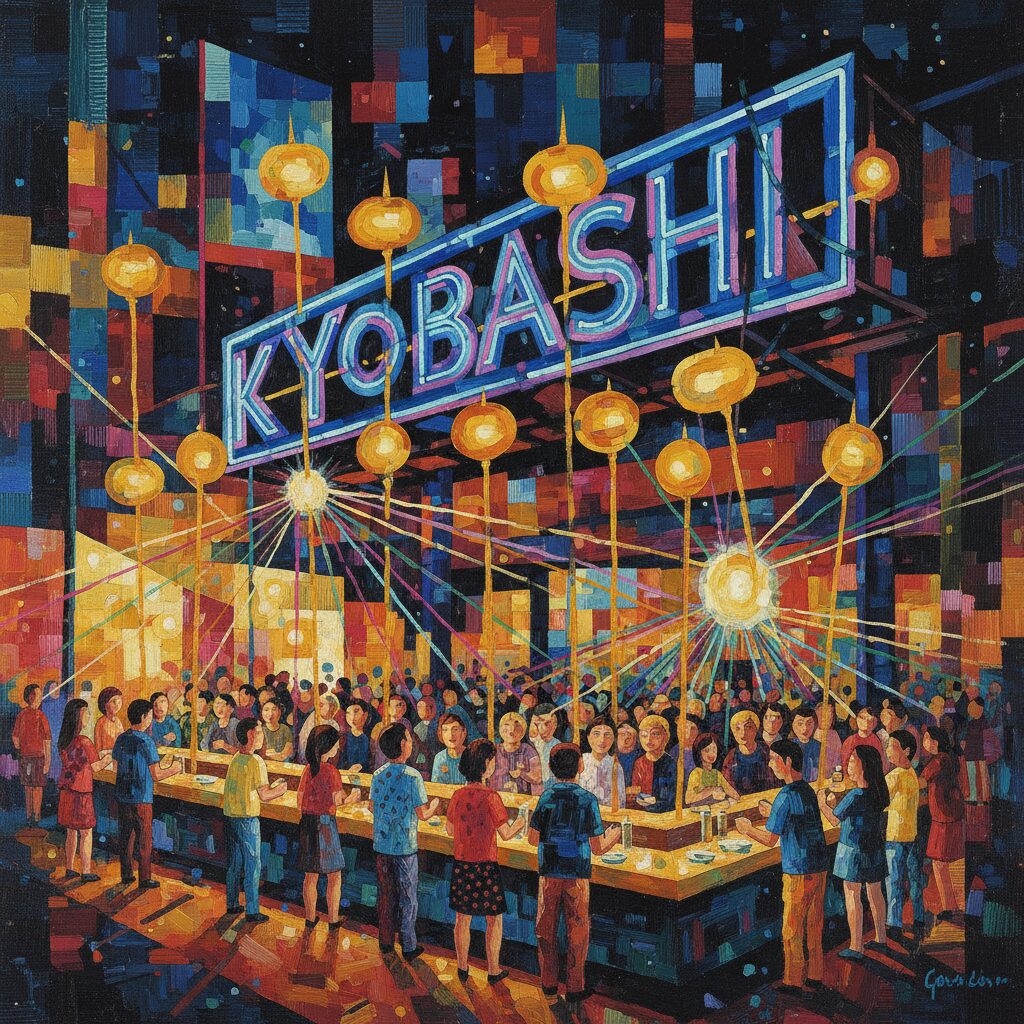

To truly grasp the magic of Kyobashi’s tachinomi scene, you first need to sense the very pulse of the area itself. Kyobashi Station serves as a vital artery in Osaka’s circulatory system, where the JR Loop Line, the Katamachi Line, the Tōzai Line, and the private Keihan Main Line all intersect. Each day, hundreds of thousands of people pass through its gates, a steady stream of commuters, shoppers, and students. This constant flow fuels the district’s restless, kinetic energy. Unlike the polished tourist hubs of Namba or the corporate towers of Umeda, Kyobashi feels lived-in, a bit rough around the edges in the most endearing way. It’s a mosaic of shiny new department stores and gritty, Showa-era shotengai—covered shopping arcades that feel like a time capsule from the 1960s. The rumble of trains overhead under the tracks creates a humming backdrop, becoming the area’s unofficial soundtrack.

As dusk settles, this energy shifts. The fluorescent office lights give way to the warm, welcoming glow of red paper lanterns, or akachōchin, hanging outside tiny bars. The hurried steps of commuters ease into a relaxed pace, drawn toward narrow alleyways. The scent of grilled meat, simmering dashi broth, and most notably, the clean, sweet aroma of hot frying oil begins to fill the air. This is Kyobashi’s golden hour, when the neighborhood sheds its daytime guise and reveals its true character as one of Osaka’s prime playgrounds for the working class. It’s a place rooted in the simple, beautiful ritual of stopping for a quick drink and a bite on the way home—a ritual we are about to join.

An Ode to the Fried Skewer: Deconstructing Kushikatsu

Before you enter your first bar, you need to know the object of our affection: kushikatsu. The name itself is a straightforward portmanteau: kushi meaning skewer (usually bamboo), and katsu, derived from katsuretsu, the Japanese phonetic form of “cutlet.” Essentially, it’s simple: various ingredients are skewered, dipped in a light batter, coated with fine panko breadcrumbs, and deep-fried to a perfect golden-brown. Yet this simplicity is misleading. The mastery of great kushikatsu lies in the details, a craft perfected over generations in Osaka’s kitchens.

The Golden Armor: Batter and Panko

The essence of kushikatsu is its coating. This isn’t the thick, heavy batter found on an American corn dog. The batter is often a closely guarded secret, a thin, liquid mixture of flour, egg, and water or milk, intended simply to hold the breadcrumbs. The real star is the panko. Unlike the coarse breadcrumbs common in Western cuisine, panko is made from bread baked without crusts, resulting in lighter, airier flakes. When fried, these flakes absorb less oil and create a texture that is incredibly crispy and delicate, breaking with a satisfying crunch at the first bite. The oil itself is crucial. Reputable establishments use a clean, high-quality vegetable oil, often a proprietary blend, maintained at a precise temperature. This high heat instantly cooks the exterior, sealing in the ingredient so it steams in its own juices. The outcome is a skewer that is surprisingly non-greasy, allowing the true flavor of the meat or vegetable to shine.

A Universe on a Stick

The sheer variety of ingredients that can be skewered and fried is astounding. The menu at a kushikatsu spot celebrates the Japanese philosophy of honoring individual ingredients. It’s a culinary democracy where humble vegetables receive the same respect as prime cuts of meat.

You’ll find the classics everywhere. Gyu-katsu (beef) is a must-try, tender and juicy. Buta-bara (pork belly) offers a richer, more indulgent bite. Ebi (shrimp) is sweet and crisp, its pink tail serving as a convenient handle. But the real adventure begins when you venture further. Try the uzura no tamago (quail egg), which becomes creamy and custardy inside its crispy shell. The renkon (lotus root) delivers a fantastic textural contrast, its lacy interior turning crisp-tender. Onions (tamanegi) become incredibly sweet and soft, a completely different experience from their raw form. Other popular options include shiitake mushrooms, green peppers (pīman), eggplant (nasu), and chicken (tori).

Then there are the more creative choices. A cube of chīzu (cheese) becomes a molten, gooey delight. Asparagus wrapped in bacon (asupara bēkon) is a perfect blend of salty and fresh. Some places feature seasonal specials, like ginkgo nuts (ginnan) in the fall or Japanese whiting (kisu) in the summer. Part of the fun is the discovery, pointing at something unfamiliar on the counter and being pleasantly surprised.

The Sacred Sauce: The One Unbreakable Rule

When your freshly fried skewers arrive, they’ll be set on a metal tray. Beside you on the counter will be a communal, stainless-steel container filled with a dark, glossy sauce. This is the heart of the kushikatsu experience, a tonkatsu-style sauce that is simultaneously sweet, savory, and tangy, with complex hints of fruit and Worcestershire. And it comes with one, single, non-negotiable rule: NO DOUBLE-DIPPING.

This isn’t just about hygiene; it’s a sacred social contract that unites everyone in the bar. You dip your skewer into the sauce once, and only once, before taking your first bite. Once your mouth has touched the food, that skewer must never return to the communal pot. This rule is posted on signs, enforced by staff, and observed by regulars. Breaking it is the ultimate faux pas. So what if you need more sauce mid-skewer? That’s where the complimentary cabbage comes into play. You’ll be given a bowl of raw, crisp cabbage wedges. These are not only a garnish or palate cleanser; they are your tools. You can use a clean piece of cabbage to scoop sauce from the pot and drizzle it onto your skewer. The cabbage is your ally. Respect the sauce, use the cabbage, and you’ll fit right in.

Mastering the Tachinomi: A Theatrical Experience

A tachinomi is more than just a spot to stand and eat. It’s a stage where, for the hour or so you spend there, you become part of the performance. There’s a rhythm, a flow, and a set of unwritten rules that make the experience smooth and enjoyable for everyone.

Finding Your Stage

As you explore Kyobashi’s arcades, you’ll come across dozens of tachinomi. Some are tiny holes-in-the-wall, little more than a counter with space for five or six people squeezed shoulder-to-shoulder. Others might be a bit larger, featuring a U-shaped bar and a little more room to breathe. The best ones are often the busiest. Don’t be discouraged by a crowded bar. A full house is a sign of quality and a well-loved local spot. The proper etiquette is to linger near the entrance, catch the eye of the taishō (the master or chef behind the counter), and hold up one or two fingers to show your party size. They will signal you in when a space is available. Squeezing into a tight spot is part of the charm. Politely excuse yourself (sumimasen) and slide into the open space at the counter. Personal space is a luxury here; shared space is the reality, creating an immediate, if temporary, sense of camaraderie.

The Opening Act: Drinks and Cabbage

Once you’ve claimed your spot, the first order of business is always a drink. Don’t even think about ordering food yet. The pace of a tachinomi is driven by the flow of alcohol. The most common order is nama bīru, a frosty mug of draft beer, which pairs perfectly with fried food. Other excellent choices include the haibōru (highball), a refreshing blend of Japanese whisky and super-carbonated soda water, or a chūhai, a shochu highball available in various fruit flavors like lemon or grapefruit. After placing your drink order, the taishō will set a metal tray in front of you, along with the standard bowl of cabbage. This signals you are ready to begin your culinary adventure.

The Main Performance: The Skewer Symphony

Ordering kushikatsu is an interactive, ongoing process. You don’t place one large order at the start. Instead, you order in small rounds, or omakase (chef’s choice) if you’re feeling adventurous. Most of the available skewers are displayed in a refrigerated glass case right in front of you or listed on handwritten paper strips taped to the walls. The easiest way for non-Japanese speakers to order is simply by pointing. Point at the raw skewers you want (kore, kudasai – “this one, please”), and the taishō will nod, grab them, and proceed to batter and fry them right before your eyes. It’s dinner and a show. They’ll usually fry two or three skewers at a time for you, placing them hot on your tray. Take your time. Savor each skewer while it’s at its peak crispiness. When you want more, simply point again. This rhythm of ordering, eating, and drinking lets you pace yourself and try a wide variety without feeling overwhelmed. The used bamboo skewers are placed in a tall cup or container on the counter, which is how the staff tally your bill at the end.

Why Kyobashi is Osaka’s Standing Bar Sanctuary

Osaka offers no shortage of dining and drinking spots. The dazzling lights of Dotonbori in Namba and the refined culinary scene in Umeda attract most international visitors. So, why visit Kyobashi? Because Kyobashi is where the true essence of Osaka’s drinking culture lives on in its most authentic form. The tachinomi here aren’t tourist traps. Prices are very reasonable, with most skewers costing between 100 and 200 yen. The patrons are almost entirely locals: office workers loosening their ties, longtime regulars who have frequented the same places for decades, and young couples on budget-friendly dates. This is not a place for performative dining; it’s about genuine connection and relaxation.

Strolling through Kyobashi Standing Drink Street, a renowned alley packed with tachinomi bars, feels like stepping onto the set of a post-war Japanese film. The buildings are old, signage faded, and the atmosphere thick with history and nostalgia. These bars aren’t sleek or minimalist. They are cluttered, lively, and full of character. You’re drinking in the very spots that have served generations of Osakans—a living connection to the city’s past. The experience is immersive in a way that more polished districts simply cannot offer. You’ll hear the raw, unfiltered Osaka-ben dialect all around you. You might even strike up a conversation with the person beside you—a brief moment of connection over a shared love of fried food and cold beer. In Kyobashi, you’re not just observing; you’re actively participating in the city’s everyday life.

A Practical Guide for the Fearless Foodie

Ready to jump in? Here’s what you need to know to confidently navigate your Kyobashi tachinomi experience.

Getting There

Getting there is very simple. Head to Kyobashi Station on the JR Osaka Loop Line. It’s only three stops from Osaka Station (Umeda) and one of the city’s most convenient hubs. Upon arrival, take the North Exit, which leads you straight into the action, with the main shotengai and the smaller drinking alleys right at your doorstep.

Timing is Everything

Although some bars open earlier, the real excitement happens between 5:00 PM and 8:00 PM on weekdays. This is when the after-work crowd arrives, and the bars become lively and full of atmosphere. Visiting during this peak period is key for the full experience. Keep in mind that tachinomi culture is about quick turnover; these aren’t places to stay for hours. Many bars close relatively early, around 10:00 or 11:00 PM, so avoid planning a late-night outing.

The Art of Bar Hopping

The heart of a night out in Kyobashi is hashigo-zake, the Japanese practice of bar hopping. The idea isn’t to get full or drunk in one spot, but to visit several venues, having just a drink or two and a few skewers at each. This way, you can enjoy the distinct atmosphere and specialties of multiple bars. One place might be known for its doteyaki (slow-cooked beef tendon stew), while another offers fantastic seasonal vegetable kushikatsu. A typical night involves hitting two or three different tachinomi.

Money, Manners, and Language

Cash remains king in these traditional spots. While some accept cards, it’s best to bring enough yen. The night won’t be expensive, but you don’t want to find yourself short. When you’re ready to leave, simply say okanjo, onegaishimasu (“check, please”). The staff will count your skewers and give you the total.

Here are a few helpful phrases:

- Sumimasen (Excuse me): To get the staff’s attention.

- Nama bīru, kudasai (A draft beer, please).

- Haibōru, kudasai (A highball, please).

- Kore, kudasai (This one, please – while pointing).

- Oishii! (Delicious!).

- Gochisōsama deshita (A polite “thank you for the meal” when leaving).

- Arigatō gozaimasu (Thank you).

A Final Toast to Authenticity

An evening spent exploring the kushikatsu tachinomi of Kyobashi is more than just a meal; it’s a cultural experience. It’s about grasping Osaka’s essence as a city that works hard, plays hard, and cherishes its food deeply. It’s about embracing a touch of beautiful chaos, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers who quickly become temporary friends, bonded by the simple joy of a perfectly fried skewer. It’s an invitation to step beyond your comfort zone, leaving behind English menus and tourist-friendly spots, and diving into the vibrant, pulsating heart of the city. So be daring. Wander down that narrow alley. Squeeze into that packed bar. Raise your glass, bite into that irresistibly crispy skewer, and savor a true taste of Osaka. You won’t regret it.