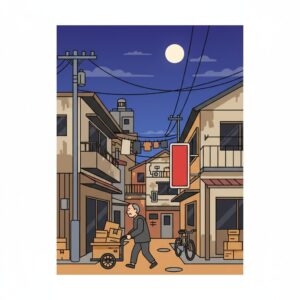

When you first arrive in Osaka, Namba hits you like a tidal wave of light and sound. The Glico Running Man, the giant mechanical crab, the endless river of people flowing through the Shinsaibashi-suji shopping arcade—it’s a sensory overload that defines the city for most visitors. This is the face of Namba, the one plastered on postcards and in travel blogs. But for those of us who live here, who are trying to understand the city’s pulse beyond the spectacle, this glittering facade is just the lobby. The real conversations, the true flavor of Osaka, aren’t happening under the bright lights. They’re tucked away in the smoky, narrow alleyways, in cramped rooms where the only decorations are peeling calendars and the laughter of regulars. This is a guide to that other Namba. It’s not about finding the “best” kushikatsu, but about understanding why a simple rule like “no double-dipping” reveals so much about the Osakan soul. It’s about learning to navigate the unwritten social codes of a ten-person standing bar and discovering that the city’s famed friendliness isn’t a simple caricature, but a complex dance of directness, humor, and communal spirit. We’re going beyond the tourist map to explore the living, breathing heart of Osaka’s kitchen, one back alley at a time.

For a deeper look at where locals truly unwind away from the main tourist drags, consider reading about why Osaka locals often ditch Namba for a weeknight drink.

The Philosophy of the Alley: Why Osaka Hides Its Best Self

Tokyo sparkles. It rises upward, forming sleek, vertical worlds in Shinjuku and Shibuya. Restaurants often present polished, branded experiences crafted for consistent comfort and reliable quality. Excellent food is certainly available, but the atmosphere is frequently curated, a backdrop for dining. Osaka, especially Namba, moves along a different axis. It extends inward, weaving through the spaces between buildings to create a horizontal maze of human-scale interaction. This is no coincidence; it reflects a fundamentally different urban philosophy.

These back alleys, called yokocho or rojiura, represent a conscious rejection of pretense. They embody the Osakan preference for honne (one’s true feelings) over tatemae (the public facade). In Tokyo, maintaining a polite, reserved exterior is an art form. In Osaka, it’s often regarded as inefficient and somewhat suspicious. Why waste time with formalities when you could be sharing a laugh or a gripe? The back-alley izakaya serves as a sanctuary for this mindset. The spaces are small, encouraging closeness. The decor is practical, not trendy. The focus is solely on two things: the quality of the food and drink, and the depth of human connection.

This is a city shaped by merchants, and the back-alley eatery is a merchant’s answer. It’s low-cost, high-turnover, and reputation-driven. A flashy sign on a busy street may draw tourists, but a tiny shop in Ura Namba thrives on word-of-mouth and the devotion of its jōren-san (regulars). The shop’s master, the taisho, is more than a chef; he is a pillar of the community. He recalls your usual drink, asks after your work, and sparks conversations between strangers squeezed elbow-to-elbow. This intimacy is the true product. The beer and yakitori serve merely as the medium.

From my personal perspective, having grown up amid the vibrant energy of Chinese food streets and markets, Osaka’s back alleys feel both foreign and intimately familiar. The noise, the steam rising from grills, the candid chatter—all echo the lively, communal dining cultures found across East Asia. Yet beneath the surface lies a distinct Japanese structure. There are unspoken but firmly upheld rules. There’s profound respect for the craft, even in the simplest dish. It’s a beautiful paradox: a chaotic, free-spirited atmosphere governed by a quiet, shared understanding. This is where Osaka parts ways with Tokyo. Tokyo’s order is explicit, designed into the system. Osaka’s order is implicit, emerging naturally from the community itself.

The Unspoken Language: Navigating Your First Standing Bar

The tachinomi, or standing bar, represents perhaps the purest form of the Osaka back-alley experience. There are no chairs for comfort, no private tables to retreat to. You are, by design, part of a temporary, ever-shifting community. For a foreigner, this can feel intimidating. The space is noisy, the menu might be just a series of handwritten strips of paper on the wall, and everyone seems to know exactly what they’re doing. Yet understanding the rhythm is easier than it looks. It’s a performance with a few essential steps.

The Entrance and the First Order

Confidence is your currency here. Don’t hesitate at the doorway. Step in, find a small spot at the counter, and make eye contact with the staff. There’s no need to wait to be seated, as there are no seats. The opening phrase is almost always the same, cutting through the noise to signal your intent: “Toriaezu, biru.” (“A beer for now.”) This phrase is Japan’s social lubricant, but in an Osaka tachinomi, it also signals: “I’m here, I’m ready, I’ll figure out the rest shortly.” It gives you time to study the menu on the wall, watch what the regulars are ordering, and take in the atmosphere.

Reading the Room

Pay attention to the flow. A tachinomi is a high-turnover setting. It’s not the place for a two-hour conversation. It’s for a quick drink and a few plates after work, a brief stop before heading home or moving on. The unspoken rule is to occupy only the space you need. Keep your bag on the floor or on a hook, not on the counter. Mind your elbows. The cramped space isn’t a flaw; it’s intentional. It encourages awareness of those around you, creating a shared sense of responsibility for the environment.

When ordering food, be decisive. Pointing is perfectly acceptable, especially if your Japanese is limited. A simple “Kore, kudasai” (“This, please”) while pointing at a menu item or even at your neighbor’s tempting dish works well. The staff are busy and appreciate straightforwardness. This is a major difference from more formal dining. In an upscale Tokyo restaurant, you might be expected to know all the proper names. In a Namba tachinomi, they’re just glad you’re hungry.

The Art of Conversation (or Silence)

One common misconception about Osaka is that you’re expected to be loud and chatty with everyone. While Osakans are generally more open to starting conversations with strangers than people elsewhere in Japan, it’s by no means required. It’s perfectly okay to stand, enjoy your drink and food, and keep to yourself. No one will find that odd. However, if a neighbor does speak to you, it’s usually a sincere effort to connect. The opening might be a simple remark about the food: “Sore, oishii de.” (“That’s tasty, you know.”) This is an invitation. You can respond with a smile and nod, or share a thought of your own. The conversation may be brief—a few exchanges before one of you finishes and leaves—but these small, fleeting interactions are what weave the social fabric of the tachinomi.

Paying the Bill: The Exit Strategy

When you’re ready to leave, catch the staff’s attention and say, “Okanjo, onegaishimasu.” (“The bill, please.”) Many tachinomi, especially older ones, operate on a system of trust. They might ask what you had or keep a mental tally. Some venues use a cash-on-delivery system, where you pay for each item as it arrives. Watch how others settle their bills. Tipping isn’t part of the culture. You pay the exact amount. As you leave, a simple “Gochisousama deshita” (“Thank you for the meal”) accompanied by a slight nod is the perfect way to close the experience. It’s a gesture of respect toward the food and those who prepared it, a small but important ritual acknowledging your participation in this unique communal space.

A Local’s Map of Namba’s Hidden Worlds

Namba is not a single entity. Its back alleys consist of various distinct micro-neighborhoods, each with its own history, vibe, and specialty. Exploring them is like reading a living map of Osaka’s cultural and economic past. This isn’t a list of restaurants; it’s an exploration of ecosystems.

Ura Namba: The Heart of Modern Izakaya Culture

Just east of Nankai Namba Station lies a dense network of alleys known collectively as Ura Namba, meaning “Back Namba.” This neighborhood is the modern core of the city’s casual dining scene. It’s loud, bustling, and vibrant with energy. The shops tend to be highly specialized: one that only serves gyoza, a bar dedicated to smoked delicacies, a tiny stand offering only premium sake with a few snacks. This focus embodies the Osakan merchant spirit—master one thing and do it better than anyone else. The competition is fierce, which keeps quality high and prices fair.

A weeknight stroll through Ura Namba immerses you in the sounds of Osaka at play: sizzling grills, clinking glasses, and above all, lively conversations and laughter. This isn’t the quiet, reflective izakaya experience of a Kyoto backstreet. It’s social fuel. People come here to unwind, vent about their bosses, or celebrate small triumphs. For residents, Ura Namba is where you go to feel the city’s pulse. It’s a reminder that, despite its challenges, this city knows how to enjoy life.

Hozenji Yokocho: A Stone-Paved Journey Back in Time

A short walk from the neon chaos of Dotonbori brings you to a narrow, stone-paved alley that feels like another world. This is Hozenji Yokocho. Lanterns cast a gentle light over the mossy statue of Fudo Myo-o at Hozenji Temple, while the air carries the scent of incense and grilled unagi. This alley represents an older, more refined side of Osaka’s culinary tradition. Many establishments here have been family-run for generations. You’ll find upscale kappo restaurants, quiet bars, and shops specializing in classic Osakan dishes like okonomiyaki served in an elegant setting.

Hozenji Yokocho challenges the image of Osaka as only about cheap, fast, and noisy food. It stands as a testament to the city’s deep appreciation for craftsmanship and tradition. Living in Osaka, you come to value these contrasts. One night you might have a quick beer and kushikatsu in a lively Ura Namba tachinomi, and the next, a more thoughtful meal in Hozenji Yokocho. It reveals the sophistication of the Osakan palate, which savors both the hearty fare of working-class heroes and the delicate, refined flavors of its artistic heritage.

The Misono Building: A Vertical Time Capsule

One of Namba’s most surreal and fascinating spots is the Misono Building. Its ground floor is a bustling, slightly gritty market that seems frozen in the 1960s. But the real secret lies upstairs. Up a plain escalator, you enter a strange and wonderful world of tiny, themed bars. Each bar is its own universe, often seating only six or seven people. One might focus on vintage video games, another on obscure horror films, another on a genre of music.

The Misono Building is a tribute to Showa-era nostalgia and Japan’s love of subcultures. It is a vertical yokocho, where every door leads into a unique passion project. The bar owners are not just bartenders but curators of their own tiny museums. This place reveals Osaka’s fondness for the niche, the quirky, and the deeply personal. It’s far removed from the mass-market entertainment of the main streets. Here, you find your tribe and enjoy a quiet drink among others who share your specific, peculiar interests. It shows that beneath the city’s loud, merchant-city facade lies a well of otaku-like passion and a longing for intimate, community-based connections.

Sennichimae Doguyasuji: The Street That Feeds the Kitchens

Understanding Osaka’s food culture is impossible without a visit to Doguyasuji. This covered shopping arcade isn’t for tourists seeking a meal; it’s for chefs and restaurant owners who prepare those meals. The street is devoted entirely to kitchenware: top-quality knives, takoyaki grills, professional pots and pans, plastic food models, and the iconic red lanterns (akachochin) that adorn every izakaya. Walking here is like seeing the city’s culinary scene behind the scenes.

Doguyasuji’s presence is a powerful symbol of Osaka’s identity as Tenka no Daidokoro (The Nation’s Kitchen). Food here is more than a product; it’s an industry, a craft, a lifestyle. The arcade’s proximity to thousands of Namba restaurants creates a symbiotic relationship. If chefs run out of a specific dish, they can walk two minutes to Doguyasuji and return without missing a beat. This practical infrastructure is quintessentially Osakan, reflecting a deep, systemic commitment to the art and business of dining found nowhere else with the same intensity. It is the hardware powering the city’s vibrant food scene and nightlife.

The Sound of Honesty: Osaka-ben in the Wild

Step into any Namba izakaya, and the first thing you’ll notice, after the aroma of grilled food, is the sound. It’s not just the loudness; it’s the melody and rhythm of the language itself. Osaka-ben, the local dialect, is an essential part of the experience. It’s faster, more direct, and more expressive than the standard Japanese you might hear in Tokyo.

For a foreigner, it can feel disorienting at first. The polite, indirect phrasing learned in textbooks seems to vanish in the steam of a hot pot. Here, communication is about efficiency and emotional honesty. When a staff member shouts “Maido!” as you enter, it’s more than a simple “Welcome.” It’s a warm, hearty greeting that roughly translates to “Thanks for your continued patronage!” even if it’s your first visit. It instantly sets a tone of informal community.

Listen for the key phrases that appear in every conversation. A delicious dish isn’t just “oishii“; it’s “meccha umai!” (insanely delicious!). Something funny isn’t “omoshiroi“; it’s “honma omoroi” (seriously hilarious). The sentence ending “nen” adds emphasis and shared understanding, similar to saying “you know?” or “isn’t it?” It draws the listener into the speaker’s perspective. For example, “Atsui na” in Tokyo (It’s hot, isn’t it?) becomes “Acchai na, honma” in Osaka (Man, it’s crazy hot, for real). The emotion is worn openly.

What outsiders often mistake for rudeness is actually a form of intimacy. In Tokyo, direct confrontation or disagreement is usually avoided to maintain harmony (wa). In Osaka, friendly verbal sparring, called tsukkomi, is a sign of affection. It’s a playful exchange where one person says something slightly absurd (the boke), and the other responds with a witty retort (the tsukkomi). You might hear a customer joke about the small size of his drink, and the taisho will reply, “What, you want a bucket?” This back-and-forth, which might seem tense elsewhere, ends with laughter on both sides. It’s a way of building rapport, testing boundaries, and finding a comfortable, human connection.

This directness also applies to opinions. An Osakan will readily tell you if they think your favorite baseball team is terrible or if they disagree with your sake choice. This isn’t meant to offend. It comes from a belief that honesty is more respectful than hiding true feelings behind politeness. In the close quarters of a back-alley bar, this linguistic honesty creates a space where people can be themselves. It’s a refreshing, if sometimes bracing, contrast to the carefully crafted social rituals of other regions. Learning to appreciate Osaka-ben is learning to appreciate the Osakan value of authenticity over performance.

The People at the Counter: Weaving the Social Fabric

An izakaya, fundamentally, is defined not by its food or décor, but by the people within it. The back alleys of Namba serve as a stage for a nightly drama featuring a recurring cast, and grasping their roles is essential to understanding the city’s social fabric.

The Taisho: The Quiet Conductor

The master of the establishment, the taisho, stands at the heart of this intimate world. Often a calm, concentrated presence behind the counter, they move with a practiced economy of motion refined over many years. Their connection with customers forms the foundation of the izakaya. While they may not engage in lengthy conversations, they are always attentive. They notice when your glass is empty, observe your reaction to a new dish, and subtly facilitate social interaction. A skilled taisho knows how to connect people, perhaps remarking to a solo diner, “This person next to you is from Hokkaido; you should ask them about the seafood there.” They serve as the human center that transforms a room full of strangers into a temporary community.

The Jōren-san: The Keepers of the Flame

The regulars, or jōren-san, are the lifeblood of any alleyway eatery. They often have a reserved bottle of shochu bearing their name kept behind the counter. They know the taisho’s family history and the off-menu items. For newcomers, watching the jōren-san is like receiving a masterclass in local etiquette. They model how to interact with staff, how to order, and how to maintain the delicate balance of being friendly without overstepping. Becoming a jōren-san is a process that requires consistency, respect for the space, and a genuine appreciation for the establishment. When the taisho greets you more personally with an “Ah, maido” and anticipates your drink order, you know you are on your way. It’s a quiet badge of honor for residents, both foreign and Japanese.

The Solo Patron: A Study in Contentment

One of the most notable features of Namba’s izakayas is the abundance of solo diners and drinkers. In many cultures, eating alone in a busy bar might feel lonely or unusual, but here, it is common and respected. Office workers in suits, young students, and elderly men and women sit contentedly by themselves, enjoying a quiet meal. This reflects a culture that honors personal time and space, even within a communal environment. There’s no stigma attached. The solo patron comes for the food, a moment of peace, or simply the pleasure of being in a lively atmosphere without the pressure to socialize. This openness makes Osaka’s back alleys surprisingly welcoming to foreigners exploring the city on their own. You can engage with the energy of the room at your own comfort level, whether that means joining conversations or simply soaking in the ambiance.

For a foreigner, finding your place in this ecosystem is a delicate dance. The initial barrier may seem high, as these are not tourist-oriented spaces. But the key is straightforward: be a good customer. Show respect, be patient, and demonstrate genuine interest. Learn a few words in Japanese, compliment the food, and avoid overstaying when the place is busy. Over time, you stop being just a customer and become part of the scene. The taisho’s nod grows warmer, a jōren-san might offer you a taste of their sake, and you realize you’re no longer merely observing the culture—you’re a small part of it. That sense of belonging, earned through quiet consistency, is one of the most rewarding experiences of living in this city.

More Than a Meal: What the Food Itself Tells You

Finally, let’s turn our attention to the food. In Osaka, food is never merely nourishment. Every dish tells a story, and every rule around it imparts a lesson in local culture. The menu of a tucked-away izakaya serves as a textbook of Osakan values.

Kushikatsu: The Sacred Rule of the Sauce

Deep-fried skewers of meat and vegetables—simple, unpretentious, and delicious. Yet the most crucial part of the kushikatsu experience is the communal pot of dipping sauce at the counter. Accompanying it is one unbreakable rule: “Nido-zuke kinshi“—no double-dipping. Once you’ve taken a bite, your skewer must not return to the sauce. This rule is more than hygiene; it’s a social contract. The sauce is a shared resource, and by respecting this rule, you honor everyone else who will use it. It perfectly symbolizes life in a crowded city like Osaka. You can be loud and individualistic, but you must respect shared spaces and resources that enable community. This rule sets a baseline of consideration, allowing for a lively atmosphere without descending into chaos.

Doteyaki: The Beauty of Unseen Effort

Often simmering in a large pot on the counter is doteyaki, beef sinew slow-cooked for hours in miso and dashi. It’s not glamorous—brown, humble, and not immediately appealing. But tasting it reveals the Osakan appreciation for deep, complex flavors developed over time. This is working-class food: cheap, filling, and incredibly satisfying. It embodies a preference for substance over superficial beauty. An Osakan would much rather enjoy something messy but divine than a beautifully plated dish without soul. Doteyaki stands as a testament to patience and the unseen labor behind true quality. It rewards those who look beyond the surface.

The Primacy of Dashi: The Invisible Foundation

Whether in a simple soup, takoyaki batter, or the base of doteyaki, the quality of dashi (broth) is essential. Osaka’s food culture rests upon it. This kombu and bonito stock forms the invisible foundation of countless dishes, imparting deep, savory umami. Even in the cheapest standing bars, bad dashi is unacceptable. This dedication reveals the heart of the Osakan craftsman. They know fundamentals matter most. You can pile on countless toppings and sauces, but if the base is flawed, the entire dish fails. This principle stretches beyond cooking, embodying a mindset that values strong foundations, honesty in materials, and doing the job right from start to finish without shortcuts. It’s the quiet pride of the shokunin (artisan) reflected in the city’s daily fare.

These back alleys and cramped, smoke-filled rooms buzzing with laughter are the soul of Namba. They showcase the city’s true character: direct, unpretentious, humorous, and deeply communal. Spending an evening there is more than just dining—it’s a lesson in Osaka’s art of living. It shows that community thrives in fleeting spaces, honesty is kindness, and the best things in life often lie hidden, waiting for the curious to peek behind the curtain.