Walk out of the gleaming, labyrinthine halls of Umeda Station, and you’re in one version of Osaka. It’s a city of soaring glass towers, of luxury department stores with impeccable service, of underground malls that stretch for what feels like miles, a seamless, air-conditioned world of efficient commerce. This is the Osaka you see on postcards, the engine of the Kansai economy. It’s impressive. It’s powerful. And for many who move here, especially from abroad, it’s the only Osaka they know. They live in modern apartments, shop at giant supermarkets, and see the city as a collection of train stations and destinations. But in doing so, they miss the city’s true pulse. They miss its soul. To find that, you need to step off the main road, push past the flapping noren curtain of a different kind of entrance, and enter the world of the neighborhood shotengai.

To the uninitiated eye, these covered shopping arcades can seem like relics. A little worn, a little dated, a chaotic jumble of mom-and-pop shops selling everything from fresh tuna to toilet brushes. You might wonder why anyone would choose this environment—sometimes drafty in the winter, noisy with the overlapping cries of vendors, visually cluttered—over the sterile perfection of an Aeon Mall. Isn’t it just a place for old folks to buy cheap vegetables? A nostalgic backdrop for a photo, but not a serious part of modern life? This is the fundamental misunderstanding. The shotengai is not just a place to shop. It never has been. It is the city’s living room, its open-air community center, its real-life social network. It is the operating system for daily life in Osaka, a place where commerce is just the excuse for the real business at hand: human connection. This isn’t a guide to finding the best takoyaki stand. This is an exploration of the invisible social architecture that makes Osaka one of the most profoundly human cities in the world, and why understanding the shotengai is the key to understanding Osaka itself.

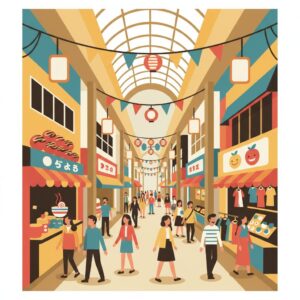

To truly grasp this social architecture, one must experience the vibrant commerce and community found within a typical shotengai.

The Unspoken Contract of the Shotengai

At the core of the shotengai experience lies a social contract—an unspoken understanding between sellers and buyers. This contract isn’t about point cards, loyalty programs, or scripted customer service enforced by corporations. It’s about mutual recognition; about being seen as a person rather than just a source of money. This is one of the most striking differences you’ll notice between daily life in Osaka and Tokyo. The capital often operates on a principle of smooth, impersonal efficiency. A visit to a suburban Tokyo supermarket is a streamlined task: you navigate the aisles, place your items on the conveyor belt, exchange polite but distant greetings with the cashier, and may even opt for a self-checkout to skip human interaction altogether. The aim is to complete the shopping with as little interruption or variation as possible. The system is designed to be flawless, predictable, and interchangeable—you could be anywhere, and the experience would feel nearly identical. However, in an Osaka shotengai, the purchase marks the start of a conversation, not its conclusion.

It’s Not Just Shopping, It’s a Daily Check-In

Observe the interactions carefully. An elderly woman, moving slowly with a cane, pauses at a small, family-run vegetable stand. She’s buying only one carrot and a block of tofu. In a large supermarket, this would be a quiet, routine transaction. Here, it turns into a consultation. The shop owner, a woman with flour on her apron, leans over the counter. “Yamada-san, konnichiwa! Your leg seems a bit better today, isn’t it?” She doesn’t just ring up the items; she inquires about what Yamada-san plans to cook for dinner, mentions that her own son has a cold, and reminds Yamada-san that a fresh delivery of sweet potatoes will arrive tomorrow. This exchange might last five minutes, despite a purchase worth only a few hundred yen. What’s really exchanged here isn’t just goods for money—it’s a wellness check. The shop owner is making sure Yamada-san is well and about. Yamada-san in turn confirms her continued presence in the community. This kind of interaction happens dozens of times per hour throughout the arcade. The butcher asks a young mother if her baby has started sleeping through the night. The fishmonger tells a regular salaryman that the best cut of bonito has just come in, knowing it’s his favorite. This is community care disguised as commerce—a safety net woven from daily greetings and casual conversations. It’s why many elderly residents can live independently with confidence. They know that if they miss a day or two at the tofu shop, someone will notice, someone will care enough to check.

The “Maido” Mindset: More Than Just “Thank You”

This difference is best expressed in a single word: “Maido.” In standard Japanese, the common greeting is “Irasshaimase,” a polite, formal invitation directed at customers as anonymous entities. In Osaka’s shotengai, however, you’ll hear “Maido!” or “Maido okini!” called out from every stall. Literally, “maido” means “every time” or “always,” but its meaning goes much deeper. It conveys, “Thank you for your business, as always.” It means, “Welcome back, we remember you.” It signifies, “You’re one of us.” Unlike “Irasshaimase,” which maintains a respectful distance between seller and buyer, “Maido” dissolves that barrier. It acts as a verbal handshake—a confirmation of belonging. This attitude fosters a loyalty no algorithm can replicate. You don’t choose a particular butcher just because his prices are cheapest. You go because he knows you, understands your preferences, and takes pride in serving you and your family. Their relationship transcends mere transactions; it’s built on trust. It’s knowing that the person selling your dinner tonight will also be there next week, and in weeks to come, and will ask how you liked tonight’s meal. It’s a profoundly human, analog system of mutual reliance in a world increasingly defined by digital anonymity.

The Architecture of Connection

The social role of the shotengai is no coincidence; it is embedded in its very design. The physical layout of these arcades fundamentally differs from that of a modern shopping mall. A mall is an enclosed, climate-controlled environment, completely sealed off from the outside world. Its goal is to guide you efficiently from store to store, maximize opportunities for spending, and provide a consistent, branded experience. In contrast, a shotengai is a transitional space. It is a public street, yet covered. It remains open to the city’s elements—the sounds, smells, and warmth—but offers protection from rain and the intense summer sun. This distinctive design fosters a different type of behavior, promoting a slower, more social pace of life.

Created for Loitering, Not Just Spending

Look around any shotengai, and you’ll notice something often omitted from modern retail spaces: places designed to linger. Benches are common, serving not only tired shoppers but also as social spots. Groups of elderly friends can be seen sitting for hours, chatting and observing the passing scene. Parents pause while their children enjoy freshly purchased taiyaki. This is not wasted space; it is intentional. The shotengai aims to be a welcoming place to simply exist without pressure to spend. The rhythm is naturally pedestrian. People stroll, stop to greet neighbors, and window-shop leisurely. The covered roof transforms the corridor into an all-weather public square, a communal area where neighborhood life unfolds naturally. During humid, rainy summers and cold winters, the arcade serves as the default gathering spot, a refuge that is always open, always accessible, and vibrant with the community’s pulse.

A Blend of Sounds and Smells

The sensory experience of a shotengai acts as a strong unifying force. Unlike the filtered air and planned background music of a department store, the arcade offers full sensory immersion in neighborhood life. Each shop adds its own note to the overall symphony. Close your eyes, and you can navigate by smell alone: the savory, sweet smoke of grilled unagi from a small specialty shop, the fresh, nutty aroma of roasting tea leaves, the sharp tang of Japanese pickles from barrels, the comforting scent of dashi broth simmering at a udon stand, the sizzle of oil as a butcher fries korokke for schoolchildren. The soundscape is equally rich and layered. There is the lively call of vendors—”Yasui yo! Oishii yo!” (Cheap! Delicious!)—not as pushy sales pitches but as urban birdsong. The clatter of bicycles over worn tiles, the rolling of metal shutters at opening and closing, the distant jingle of a Pachinko parlor, children’s laughter, and snippets of gossip exchanged between shoppers all blend together. This shared sensory environment builds a strong sense of place. It is instantly familiar and deeply reassuring to residents. It represents the authentic, unfiltered soundtrack of their everyday lives, a constant reminder that they belong to a lively, living community.

Shotengai as the Neighborhood’s Living Room

Beyond its commercial role, the shotengai functions as the neighborhood’s central hub for information and social connections. It is where news is shared, problems are addressed, and the community strengthens its sense of identity. In an era dominated by Google searches, the shotengai persists as a powerful analog alternative—a network of human expertise and trust operating on a hyper-local scale. Essentially, it serves as the neighborhood’s collective brain and compassionate heart, a one-stop resource for the practical and emotional demands of everyday life.

The Guardians of Local Knowledge

Picture moving into a new apartment in Osaka, and in the heat of August, your air conditioner breaks down. Your first impulse might be to search online for a repair service, sifting through anonymous reviews and corporate sites. But the typical Osakan instinct is to visit the shotengai and ask around. You might approach the woman at the fruit stand or the elderly man running the small electronics shop that still fixes vacuum cleaners from the 1980s. Within minutes, they won’t just give you a number; they’ll say, “Ah, you should contact Tanaka-san. His son just got married last month. Tell him Suzuki from the fish shop sent you. He’ll take good care of you.” This illustrates the power of the shotengai network. The shopkeepers act as nodes, custodians of decades of local knowledge. They know who is trustworthy, who delivers quality work, and who charges fairly. They are the gatekeepers of the community’s practical wisdom. This network is invaluable, especially for those less comfortable with digital technology, like the elderly, or for newcomers finding their way. Relying on personal referrals over anonymous online ratings is a defining feature of the city’s social fabric. It is a system grounded in reputation and long-standing relationships, sharply contrasting with the transactional nature of the modern gig economy.

From Cradle to Grave: The Shotengai Lifecycle

A shotengai is not a destination for specialty shopping; it embodies life itself. Its shops reflect the evolving needs of a community through each phase of life. As a small child, your first taste of independence might be receiving a 100-yen coin to visit the dagashiya (cheap candy store) and pick out sweets. As a student, you grab a warm, greasy, delicious korokke or menchi-katsu from the butcher shop as an after-school treat. When you move into your first apartment, instead of a big-box store, you visit the shotengai’s kitchenware shop to buy your first rice cooker and set of bowls, receiving the owner’s advice on what will last. As a young parent, you rely on the vegetable vendor to recommend the freshest spinach for your baby’s food. And as you grow older, the shotengai becomes your main social space—a place for a gentle stroll, a familiar chat, and staying connected to the world. The array of businesses tells the story of the community: the butcher, the fishmonger, the tofu maker, the futon shop, the neighborhood clinic, the pharmacy where the pharmacist knows your medical history, the small bookstore, the traditional kissaten (coffee shop). It is a complete ecosystem designed to support life from beginning to end. This lifelong, comprehensive service is what deeply embeds the shotengai in the identity of its residents.

Deconstructing the “Friendly” Cliché: Why Osaka Feels Different

One of the first things people often say about Osaka is that its residents are “friendly.” While this is not incorrect, the comment is somewhat simplistic and overlooks the deeper cultural dynamics involved. The friendliness in Osaka differs from the polished, service-oriented hospitality typical of upscale Tokyo hotels. It is more earthy, straightforward, and deeply connected to the city’s merchant heritage. The shotengai serves as the ideal setting to observe these behaviors, understand the reasons behind the stereotype, and appreciate the distinctive style of communication in Osaka.

Pragmatism Over Polish

Tokyo’s culture, like much of mainstream Japanese culture, highly values tatemae—the public facade and the smooth, harmonious presentation. Customer service there is an art of politeness, deference, and flawlessness. In Osaka, however, there is a greater emphasis on honne—the genuine, underlying truth. This is reflected in a communication style that may seem blunt to outsiders but is locally perceived as intimate. The vegetable seller in the shotengai won’t just bow and thank you; she might glance at your basket and say, “Just that today? You look a bit pale; you should eat something rich in iron!” Or the butcher might tease, “Buying the pricey wagyu again? Must be bonus time!” In Tokyo, such personal remarks from shopkeepers would be nearly unthinkable, considered a breach of polite distance. In Osaka, they indicate that you’re seen as a real person, not merely a source of income. They engage with you rather than perform a service for you. This straightforwardness is a practical form of care, focused not on perfection but on being helpful, sincere, and authentic.

The Culture of “Chotto Omake”: The Little Extra

Any discussion of Osaka’s merchant culture is incomplete without mentioning omake. Meaning “a little extra” or “a bonus,” it’s a common practice in the shotengai. When you’re a regular customer buying a few apples, the owner might toss an extra one into your bag with a wink and a cheerful “Hai, omake!” If you purchase fish, you might receive a handful of green onions as a bonus. It’s rarely a substantial amount. It’s not a calculated discount or a formal loyalty scheme aimed at maximizing retention. Rather, it’s a gesture—a spontaneous, human expression of gratitude and connection. The omake conveys, “I see you. I appreciate you choosing my shop over a supermarket. We share a bond.” It transforms an ordinary commercial transaction into a moment of positive social exchange. This small act of generosity counters the cold, impersonal nature of modern retail. It embodies the “Maido” spirit, a continual reaffirmation of the relationship between shop and community. This tradition prioritizes goodwill over pure profit and forms a cornerstone of the Osakan business ethos (shobai).

Shared Vulnerability and Mutual Support

The shotengai are not made up of corporate chains. The vast majority of shops are small, family-run businesses often handed down across generations. This creates a strong sense of shared identity and vulnerability between shopkeepers and customers. They are neighbors who live in the same community, send their children to the same schools, and face similar economic challenges. This shared environment fosters a deeply ingrained culture of mutual support. It’s not an abstract ideal but a lived daily reality. Shopkeepers act as informal guardians of the neighborhood—they watch out for children walking home from school, notice when an elderly resident’s routine shifts, and when local festivals take place, the shotengai association organizes the events, hanging lanterns and setting up food stalls. This is the true purpose of the shotengai: a system of interdependence and social safety net, composed of countless small moments of daily interaction. Foreigners might view the shotengai as merely nostalgic collections of old shops. They are not. Their appeal lies in the vibrant, practical community network these shops enable. The food they sell is simply the medium for a far more significant exchange.

The Future of the Hub: Challenges and Evolution

Portraying the shotengai as a perfect, unchanging utopia would be misleading. These community hubs face significant challenges in the 21st century. With an aging population, many shop owners are retiring without successors to continue their family businesses. The convenience of online shopping and the strong allure of large, modern shopping malls have drawn customers away. Throughout Japan, “shutter-gai”—formerly vibrant arcades with most metal shutters now permanently down and painted facades fading in the sun—are increasingly common. The shotengai is not a museum artifact; it is a living ecosystem, and like any ecosystem, it remains vulnerable.

New Blood, New Ideas

Still, claims of the shotengai’s demise are greatly exaggerated. In Osaka, many don’t just survive—they adapt and evolve in remarkable ways. A new generation is revitalizing these old spaces, attracted by their authenticity and low overhead. You might find a third-generation fishmonger who has added a small, upscale standing sushi bar in a corner of his shop, serving the freshest fish of the day. A traditional futon store may be managed by a grandson who also runs an online shop. Alongside decades-old vegetable stalls and pickle shops, fresh businesses are moving in. A stylish third-wave coffee roaster may open in a former watch repair space. A craft beer pub might take over an old liquor store. An art gallery or a small design studio can find a home in a former rice shop. This blend of new energy creates a lively mix of old and new. The key to their success often lies in embracing the core spirit of the shotengai. The trendy barista quickly learns his regular customers’ names. The craft beer pub owner organizes neighborhood events. They understand they are not merely renting retail space but joining a community. They adapt to the neighborhood’s rhythm, adding their own voice to the ongoing story of the shotengai.

Your Role as a Resident

For any foreigner living in Osaka, the local shotengai is more than a place to observe culture—it is a place to engage with it. It offers your greatest chance to move from outsider to an integral part of the neighborhood. It may feel intimidating at first: interactions are quick, the dialect can be thick, and unwritten rules abound. However, the barrier to entry is lower than it seems. The key is becoming a regular. Start small. Instead of buying all your groceries at a supermarket, purchase one item at the shotengai. Perhaps begin by getting your bread from the local bakery, then your vegetables from a particular stall. At first, you might simply point and pay. Soon, you’ll catch the rhythm. Try a simple “Konnichiwa” (Hello) when you arrive and “Arigato gozaimasu” (Thank you) when you leave. After a few visits, the shop owner will recognize you and may ask where you’re from. One day, you might be surprised by a warm “Maido!” That’s the moment you’ve crossed a threshold—you are no longer just a customer; you are a neighbor. By engaging with your shotengai, you do more than buy fresher food: you plug yourself into the city’s lifeblood. You build a network of familiar faces, a support system, and a genuine sense of belonging. You’ll discover the city’s true character, not in neon-lit tourist areas, but through the simple, meaningful daily human connections that keep Osaka’s heart beating, one friendly greeting at a time.