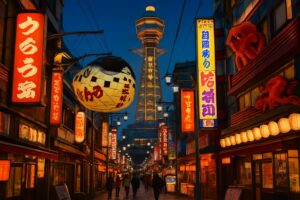

Ever wondered what an entire city’s personality, its unfiltered id, would look like if you stretched it out over two and a half kilometers and put a roof over it? If you took all its noise, its contradictions, its love of a good deal, and its obsession with delicious, unpretentious food, and crammed it into one long, chaotic, exhilarating artery? That’s Tenjinbashisuji Shopping Street. Forget what the guidebooks tell you. This isn’t just the longest shopping arcade in Japan. It’s a living, breathing entrance exam for understanding Osaka. It’s the city’s ultimate litmus test. Walk its length, from the sleepy northern entrance at Tenjimbashisuji 6-chome down to the spiritual anchor of the Tenmangu Shrine at its southern foot, and you’ll know. You’ll know if the soul of this city resonates with yours. For the adventurous foodie and the determined bargain hunter, it’s a paradise. A sprawling, seemingly endless buffet of stimulation. But for those accustomed to the polished order of Tokyo or the serene quiet of Kyoto, it can be an overwhelming sensory assault. The clatter of pachinko parlors bleeds into the sizzle of frying croquettes. The shouted greetings of fishmongers compete with the tinny jingles of drugstore promotions. It’s a place that forces you to engage, to be present, to navigate a current of humanity that flows with its own peculiar, unwritten rules. This isn’t a curated cultural experience; it’s the raw, uncut daily life of Osaka, served up on a 2.6-kilometer-long platter. Before we dive into the beautiful chaos, let’s get our bearings. This is the beast we’re about to tackle.

To fully prepare for this sprawling adventure, be sure to consult our practical guide to navigating Tenjinbashisuji.

More Than a Market: The “Akindo” Spirit and the Art of the Deal

To truly grasp Tenjinbashisuji, you first need to understand that it’s not really about shopping—not in the modern, transactional sense. It represents commerce in its oldest, most human form. This is the domain of the akindo, the traditional Osaka merchant. The akindo spirit is worlds apart from the quiet, bowing, impeccably polite service you might encounter in a Ginza department store. The philosophy here is rooted in communication, relationships, and a concept central to the Osaka mindset: value. Not just low prices, but genuine, undeniable value for money.

“Mokkari-makka?” – It’s More Than Just Money

You’ll hear this call echoing down the arcade—a rhythmic exchange between shopkeepers and their regular customers. “Mokkari-makka?” one will shout, wearing a broad grin. The literal meaning is, “Are you making a profit?” In Tokyo, asking someone so directly about their finances would be a stark breach of etiquette. Here, though, it’s as common as saying “hello.” The typical response, given with a shrug and a wry smile, is “Bochi-bochi denna: “So-so,” or “Can’t complain.” This exchange is the key to everything. It’s not a genuine inquiry into their books; it’s a verbal handshake, a ritual affirming a shared identity. It means, “We’re both in this together, trying to make a living, trying to get by.” It’s a form of commerce as performance—a playful nod to the hustle that drives this city. This spirit breathes life into every interaction. The woman selling tsukemono (pickled vegetables) won’t just bag your purchase; she’ll ask where you’re from, make a comment on the weather, and tell you which pickle pairs best with white rice. The butcher at a famed croquette stand might slip in an extra, slightly misshapen piece with a wink—a small gift called an omake. This freebie is a cornerstone of Osaka’s business culture. It’s not a calculated marketing strategy but a gesture of goodwill. It’s the shopkeeper saying, “Thanks for your business. Come again.” This marks a fundamental contrast with Tokyo, where service tends to prioritize flawless, seamless, yet ultimately impersonal precision. In Osaka, service is defined by human connection, however brief or boisterous it may be. They’re not merely selling you a product; they’re inviting you, if only for a moment, into their world. This can surprise newcomers—you’re expected to engage, respond, and join in the lively energy of the exchange. A quiet, hesitant customer may be met with a friendly but firm nudge to decide. It’s not rudeness; it’s efficiency. They have other customers to serve, more jokes to tell, and more business to do.

The Unspoken Rules of Bargaining (And When Not To)

With handwritten signs bearing prices slashed in red ink and loud, energetic sales pitches, you might assume you’ve stepped into a marketplace where haggling is customary. This is a common and crucial misconception. Tenjinbashisuji is not a Moroccan souk or a Thai night market. Trying to bargain over the price of a 100-yen korokke (croquette) or a 300-yen bowl of udon will earn you a bewildered look or, worse, good-natured laughter at your expense. The “bargain” here isn’t something to negotiate. It’s offered upfront—often at shockingly low prices. The value lies in the quality you receive for that price. The real game isn’t haggling; it’s being sharp enough to spot the best deals as they arise. The true art of the bargain is timing and observation. Keep an eye out for the “taimu seru” (time sales), usually held late in the afternoon as shops look to clear out remaining stock. This is when bento boxes, sushi packs, and fried foods get marked down by 30, 40, or even 50 percent. The calls get louder, the crowds denser, and a sense of urgent opportunity fills the air. The bargain is also in the omake, that little bonus. It’s in building a rapport with the vendor. If you become a familiar face at a fruit stand, don’t be surprised if the owner starts giving you the better looking apples or throws in an extra mikan orange. That’s Osaka loyalty. It’s not tracked by points or plastic cards, but by human recognition. The core philosophy is straightforward and pragmatic: offer a good product at a price so fair it feels like a steal, treat customers like neighbors, and they will return. It’s a bold, upfront honesty that defines the local approach to business and life in general.

The “Kuidaore” Philosophy in Action

There’s a well-known phrase in Osaka: kuidaore, which translates rather dramatically as “eat until you drop and go bankrupt.” Though mostly a saying, it reflects a profound cultural truth. In Osaka, food is more than mere sustenance; it serves as the main form of entertainment, social currency, and a source of fierce local pride. And Tenjinbashisuji stands as the grand shrine of kuidaore. Stretching 2.6 kilometers, it resembles a never-ending buffet line showcasing the city’s passion for affordable, fast, and incredibly delicious food. This isn’t about Michelin stars or hushed, refined dining; it’s about efficiently and unpretentiously satisfying the city’s enormous collective appetite.

Beyond Takoyaki and Okonomiyaki

Yes, there are plenty of excellent takoyaki (octopus balls) and okonomiyaki (savory pancakes) stalls. But to truly grasp how Osaka eats, you must look beyond these famous staples and tune into the everyday rhythm of the city’s food. The core of the street’s culinary scene is found in the osozai-ya—delis offering an overwhelming variety of prepared dishes. You’ll spot glossy piles of simmered pumpkin, bright green spinach dressed with sesame, fried chicken, grilled fish, and countless other staples of Japanese home cooking. Here, locals, from busy mothers to single office workers, pick up dinner. It offers a glimpse into the real Osaka kitchen. However, the most iconic food experience on the street might be the humble fried snack. Standing before a legendary place like Nakamura-ya, a butcher shop famous for its korokke for decades, you witness the purest form of the kuidaore spirit. A queue of people, from high school students to elderly couples, waits patiently. For less than 100 yen, they receive a golden, panko-crusted potato patty in a small paper bag and eat it immediately, steam rising in the air. This is the quintessential Osaka snack—hot, savory, unbelievably cheap, and requiring no ceremony. It’s a moment of pure, unfiltered pleasure amid a hectic day. This sharply contrasts with food culture in much of Tokyo, which often feels more specialized and segmented. In Tokyo, you visit a ramen shop for ramen, a tempura shop for tempura. The experience can be sublime but compartmentalized. In Tenjinbashisuji, boundaries blur. You can enjoy a world-class croquette from a butcher, then fresh sushi from a tiny standing counter next door, and finish with a carefully brewed pour-over coffee at an old-school kissaten (coffee shop) that looks unchanged since the 1960s. Here, the pursuit of good food is democratic and embedded in daily life; it’s not a special occasion—it’s just another Tuesday.

The Croquette Hierarchy and the Sushi Standoff

Let’s pause on the croquettes, as they reveal much about the culture. Every local has their favorite, many choosing Nakamura-ya for its classic: a perfectly seasoned blend of potato and ground meat fried to a flawless crisp. But the competition is fierce. Other shops highlight creamy crab croquettes, sweet corn variations, or curry-flavored bombs. Fans passionately debate which is best. This goes beyond a snack; it’s about loyalty, tradition, and the conviction that even the simplest food can and should be perfected. The same applies to sushi. Hidden in side streets or right on the main avenue are tiny sushi shops with only a few seats or a standing counter. Places like Harukoma Sushi are local legends, known for huge cuts of fish on small rice pads, all at astonishingly low prices. The experience is a display of speed and skill. You squeeze into a space, shout your order to the chef, and moments later, a plate appears. You eat, pay, and move aside for the next in the perpetual line outside. There’s no lingering or quiet savoring; it’s a fast-paced refueling station for sushi lovers. This is often misunderstood by foreigners and Tokyoites alike, who see the crowds and speed and assume it means cheap, low-quality food. But that misses the point entirely. Osakans possess a finely tuned palate, especially for value. These establishments have lasted generations because they offer exceptional quality for the price, having perfected their craft and streamlined their service to serve the maximum number of people without sacrificing quality. It’s a business model born from the city’s pragmatic, demanding, and food-obsessed spirit.

The Sensory Overload: A Feature, Not a Bug

It’s crucial to be honest about the experience. For newcomers, walking through Tenjinbashisuji during peak hours can overwhelm the senses. The air carries a unique mix of scents: the sweet soy sauce from grilling unagi (eel), the savory aroma of dashi broth from udon shops, the deep greasy fragrance of frying oil, and the sweet smell of red bean paste from a taiyaki stand, blending together. It creates an olfactory map of the street. Then there’s the noise: the constant, overlapping calls of vendors, the jingles of pachinko machines, the rumble of shoppers’ carts, and the nonstop chatter of countless conversations. Unlike the almost reverent silence of a high-end Tokyo food hall, where every item is perfectly displayed behind gleaming glass, Tenjinbashisuji is loud, messy, and vibrant. Food is cooked openly before you; it steams, sizzles, and drips. This can feel chaotic and overwhelming. But thriving in Osaka means learning to see this as a feature, not a flaw. This sensory overload signals life and authenticity. It’s the sound and smell of a city openly passionate about its food. It doesn’t hide behind closed doors or present itself in sterile settings. Instead, it shares its love for food right here, right now, in all its glorious, delicious disorder. Embracing this is the first step toward eating—and living—like a true Osakan.

The People’s Runway: Life and Style on the Street

Beyond the commerce and cuisine, Tenjinbashisuji is, above all, a stage for everyday life. It serves as the city’s grand promenade, offering a cross-section of Osaka society rarely seen in the trendy districts of Umeda or Namba. The style here isn’t shaped by fashion magazines or global brands but by a strong pragmatism, a hint of flamboyant individualism, and a deeply rooted sense of community. This is where the genuine, unfiltered Osaka comes alive.

Leopard Print and “Chari” Culture

Let’s confront the stereotype directly: the Osaka obachan (a term for middle-aged or older women) and their well-known affection for leopard print. Indeed, you will see it—and tiger stripes, and zebra patterns—on blouses, trousers, handbags, sometimes all at once. To outsiders, it’s often a source of amusement, a cliché. But understanding the leopard print is key to grasping a core aspect of Osaka’s personality. In a country that often values conformity and understated elegance, embracing such a loud, bold pattern is a statement. It declares, “I am here. I am not invisible. And I don’t care what you think.” It’s a visual expression of the city’s straightforward, confident, and unapologetically unpretentious character. This practicality extends to the dominant mode of transportation: the bicycle, or chari. The arcade flows with both pedestrian and bicycle traffic going in all directions. You’ll see mothers on electric-assisted mamachari bikes with one child seated in front and another on the back, groceries dangling from the handlebars. Elderly men in business attire weave through the crowds, and grandmothers pedal at a measured pace. Navigating this shared space requires urban intuition; there are no marked lanes or traffic lights. Instead, it relies on subtle signals: a slight handlebar turn, a quick glance, the soft ring of a bell. It may appear chaotic, yet it functions as a beautifully self-organizing system. This physical flow reflects how Osaka society operates—slightly messy on the surface but founded on a shared, unspoken understanding allowing everyone to move efficiently.

A Community, Not a Crowd

One of the most noticeable differences between a crowded street in Osaka and one in Tokyo is the nature of the crowd itself. Standing amidst the throng at Shibuya’s famous scramble crossing, you’re surrounded by thousands but feel utterly anonymous. Each person is an island, focused on their own path, avoiding eye contact, maintaining a bubble of personal space. In Tenjinbashisuji, it’s the opposite. Even when packed shoulder to shoulder, there’s a tangible sense of shared space and community. Shopkeepers don’t remain tucked behind counters; they stand at their store entrances, engaging with passersby. They chat with neighboring vendors across the arcade, exchanging jokes and gossip. People make eye contact, say “Sumimasen” (Excuse me) with a nod and smile when squeezing past. Strangers may comment on the groceries you carry or ask where you got that delicious-looking takoyaki. Many foreigners initially call this simple “friendliness.” But it’s more specific—a mindset that sees public spaces as communal living rooms rather than neutral transit zones. People aren’t obstacles to avoid but potential conversation partners and fellow neighborhood members. This is why Osakans are reputed to be nosy—it stems from genuine curiosity and a belief that, to some extent, everyone’s business is everyone’s business. While this can be startling if you prize privacy and anonymity, it’s also the source of the city’s warmth and strong neighborhood ties. Here, you aren’t a faceless consumer but a participant in a vibrant, ongoing 2.6-kilometer-long conversation.

The Practicalities of Surviving and Thriving

Conquering Tenjinbashisuji is not just about endurance; it requires strategy. Knowing how to approach this challenge, when to visit, and how to communicate can turn the experience from an overwhelming ordeal into one of the most rewarding ways to understand your new home city. It takes some planning and a willingness to adapt to the local rhythm.

It’s a Marathon, Not a Sprint

The street’s defining feature is its length, which deserves respect. Attempting to “do” the entire stretch in an hour will only lead to exhaustion and sensory overload. The best way is to treat it like a hike—start at one end and commit to walking the full length. The northern end, near Tenjimbashisuji 6-chome station, tends to be quieter with a more residential, local vibe. As you head south, block by block (each segment called a chome), the energy builds. Shops cluster, crowds grow denser, and the variety of food options becomes more enticing. The street culminates near its southern end, by Osaka Tenmangu Shrine—the area’s spiritual center and the site of the famous Tenjin Matsuri, one of Japan’s greatest festivals. Walking north to south feels like moving from a peaceful neighborhood into the bustling commercial heart of the city. Reversing direction, starting at the shrine and heading north, offers a gradual decompression. Choose a direction and take your time. Pause for coffee. Sit on a bench and watch people. Explore the smaller side alleys (yokocho) branching off the main street, where you’ll find tiny specialist shops and hidden bars. Don’t just rush through; let yourself be immersed.

When to Go and When to Flee

Tenjinbashisuji’s atmosphere shifts dramatically by time of day and day of the week. To experience its purest, most local character, visit on a weekday morning, when residents do their daily shopping. The pace is calm, crowds manageable, and the arcade feels like a functional neighborhood hub. Lunchtime, from around noon to 2 PM, sees a rush of office workers and students, creating a frantic energy around popular food stalls and restaurants. Late afternoon, from 4 PM onward, is prime time for food bargains as the taimu seru kicks in. This is ideal for a culinary adventure, but be ready for crowds. Weekends, particularly Saturday afternoons, are peak intensity. The street becomes a bustling river of shoppers, families, and tourists—exciting yet overwhelming if you dislike crowds. The same applies around the Tenjin Matsuri in late July, when the whole area transforms into a vast festival ground. For locals, sweet spots are often random Tuesdays at 11 AM or Thursdays at 3 PM—times to explore at your own pace and feel less like a tourist and more like a local.

The Language Barrier and the “Osaka-ben” Advantage

You can manage with standard Japanese (hyojungo) or just gestures. But to truly unlock Tenjinbashisuji, learning a few phrases of the local dialect, Osaka-ben, is like discovering a secret key. This dialect is famous across Japan for being more direct, expressive, and musical than Tokyo standard. Instead of the usual “Arigato gozaimasu,” try a warm “Ookini,” meaning “thank you” with a friendly familiarity that shows your effort. When something is not good or possible, instead of “dame desu,” you’ll hear the sharp “akan.” A very useful shopping phrase is “Kore,なんぼ?” (“How much is this?”), a casual, direct way of asking price compared to the standard “Kore wa ikura desu ka?” This directness defines Osaka communication. It isn’t rude but efficient and honest. This style can confuse foreigners and Japanese visitors from other regions—what seems like bluntness is simply a different way of communicating that values clarity and connection over formal politeness. A shopkeeper might ask direct questions about your needs, not to be pushy but to save time. Embracing this directness and trying to mirror it warmly will transform your interactions. It shows you understand the local culture and are ready to engage on its terms.

Why Tenjinbashisuji is the Ultimate Osaka Litmus Test

After walking the entire 2.6 kilometers, navigating past bicycles, savoring a piping hot croquette on the street, and sharing a knowing smile with a shopkeeper, you’ll have your answer. Tenjinbashisuji is more than just a collection of shops and restaurants. It is a concentrated, high-proof essence of Osaka itself. It embodies the akindo spirit of practical, relationship-driven commerce. It reflects the kuidaore philosophy of celebrating life through flavorful, accessible food. It’s the city’s loud, unapologetic, and profoundly human heart, beating beneath a long arcade roof. It’s a place that refuses to be polished or sanitized for outsiders. It is exactly what it is—take it or leave it. This is why it serves as the perfect personal test for anyone considering making a life here. If you walk its length and find the constant noise grating, the crowds overwhelming, and the directness of the people off-putting, it’s a telling sign. The aspects of the street that unsettle you are not exceptions; they are core traits of Osaka’s character. The city’s energy may simply be incompatible with your own. But if you find the chaos exciting, if you appreciate the beauty in its well-worn functionality, if the roar of the crowd sounds like music to your ears, and if the taste of a simple, perfectly fried piece of food purchased for a few coins brings you genuine joy, then you’ve passed the test. You’ve grasped something essential about this place. You’ve discovered a city that values substance over style, community over anonymity, and a good, hearty laugh over polite silence. You’ve found a home.