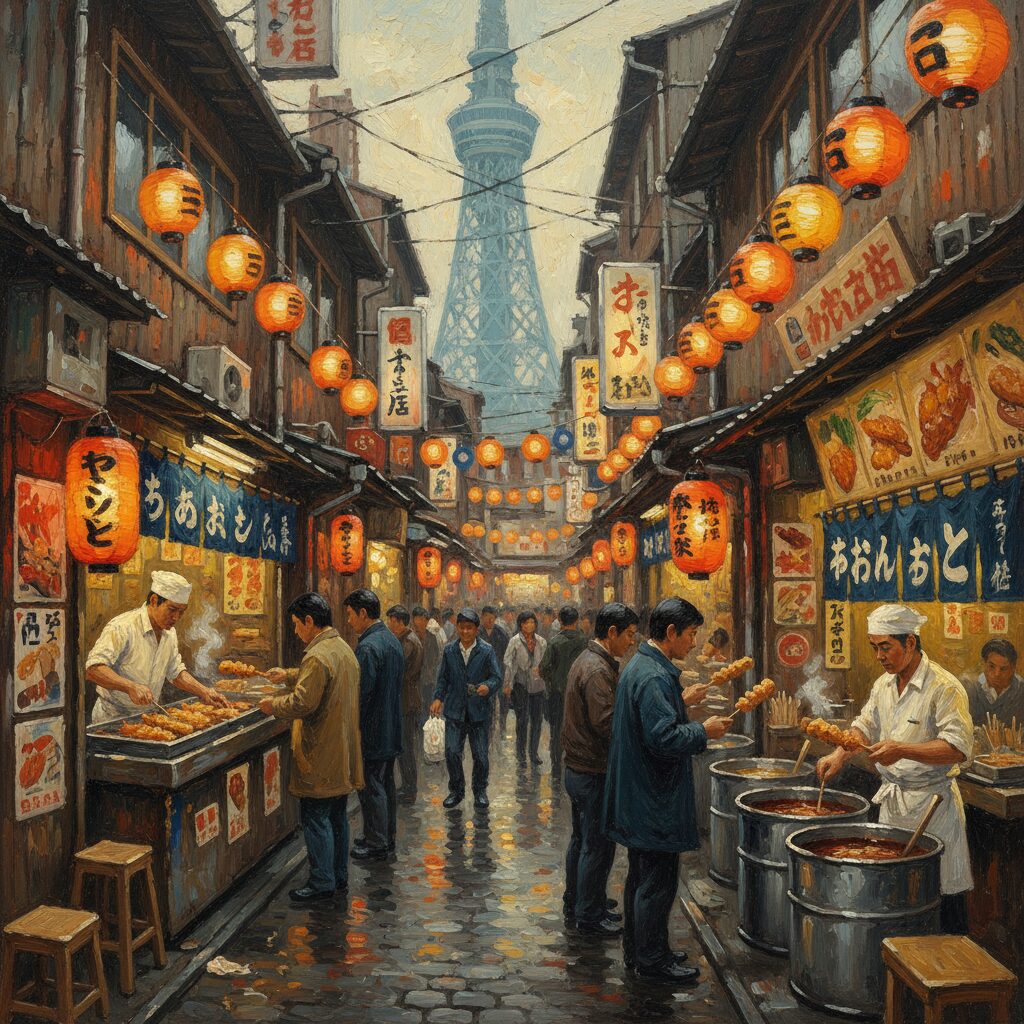

There’s a certain kind of magic that happens when you emerge from the tiled tunnels of Osaka’s subway system. The air changes, the light shifts, and the rhythm of the city pulses with a different beat. This transformation is never more profound than when you step out of Dobutsuen-mae Station and find yourself at the gates of Shinsekai, the “New World.” This is not the sleek, futuristic Japan of glossy magazines, nor is it the serene, temple-studded landscape of ancient capitals. Shinsekai is something else entirely—a district caught in a beautiful, stubborn time warp, humming with the energy of a festival that never quite ended. It’s a place where the glow of neon signs reflects in puddles on worn pavement, where the clatter of shogi tiles spills from open-fronted parlors, and where the air is thick with the irresistible, savory perfume of its reigning culinary king: kushikatsu. This neighborhood, radiating outwards from the iconic Tsutenkaku Tower, is the undisputed heartland of these deep-fried skewers, a dish as unpretentious and full of character as Osaka itself. To explore the old-school kushikatsu joints that line the narrow alleys here is to do more than just eat; it’s to take a bite out of the city’s very soul, to taste its history, its resilience, and its unabashed love for good food and good times. This is a journey into the warm, golden-brown center of Osaka’s culinary identity, a pilgrimage for anyone seeking flavor that is unapologetically bold and deeply authentic.

To truly understand the history and cultural significance of these golden skewers, you can explore our deep dive into the world of kushikatsu in Shinsekai.

The Echo of a Bygone Era: Shinsekai’s Living History

To grasp the essence of Shinsekai, you first need to understand its history. This district didn’t develop naturally over centuries; it was born from ambition, a burst of modernistic enthusiasm at the start of the 20th century. In 1903, Osaka hosted the fifth National Industrial Exposition, a grand event designed to showcase Japan’s rapid modernization to the world. The area, then just vacant land, was transformed. After the exposition ended, the city decided to establish a permanent entertainment district on the site—a futuristic vision they named Shinsekai, or “New World.” Its design was bold, divided into two distinct sections. The northern part was inspired by Paris, featuring a steel-framed tower at its center as a deliberate tribute to the Eiffel Tower. The southern section took cues from New York’s Coney Island, complete with an amusement park and a striking cable car called Luna Park. When it opened in 1912, Shinsekai was the height of modernity and excitement, a dazzling playground for a nation stepping onto the global stage. It was home to cinemas, theaters, bustling restaurants, and endless novelties, attracting visitors from across the country eager to marvel at its Western-inspired wonders.

However, the district’s golden era was short-lived. The original Tsutenkaku Tower was damaged by fire and eventually dismantled for wartime efforts in the 1940s. Post-war Japan shifted economic priorities, and Shinsekai, once a bright symbol of the future, was largely neglected. Investment moved to other parts of Osaka like the commercial centers of Umeda and Namba. Shinsekai, overlooked and underfunded, began to decline. Luna Park closed, and the district gained a reputation for being rough, a refuge for laborers and the down-and-out. Yet this very neglect became its preservation. While other parts of Japan modernized rapidly, demolishing the old for the new, Shinsekai stayed frozen in time. Its pre-war street layouts, Showa-era architecture, and unpretentious working-class spirit were preserved as if in amber. This is the Shinsekai we see today: not a carefully curated historical theme park, but an authentic, living relic. Walking its streets is like stepping onto a film set from the 1950s or 60s. The oversized, hand-painted signs, vintage pachinko parlors, and its resolute refusal to conform to modern aesthetics give the area its powerful, irresistible charm. It stands as a testament to resilience—a district that wears its weathered heart openly, offering a glimpse into a chapter of Japanese urban history nearly erased elsewhere.

The Golden Skewer: Demystifying the Art of Kushikatsu

At the culinary heart of Shinsekai lies kushikatsu, a dish that appears simple but delivers endless satisfaction. The name is a direct combination of “kushi,” meaning skewer (usually bamboo), and “katsu,” a shortened form of “katsuretsu,” the Japanese adaptation of “cutlet.” Essentially, it consists of an ingredient—whether meat, seafood, or vegetable—threaded onto a skewer, dipped in a light batter, coated with fine panko breadcrumbs, and deep-fried to a perfect golden crisp. However, describing it merely this way overlooks the artistry and cultural significance embedded in every bite. Kushikatsu is a people’s dish, born from the need for affordable, quick, and filling meals for the laborers who built and frequented Shinsekai in its early days. It’s an unpretentious cuisine, meant to be eaten standing, often accompanied by a beer, offering a brief, delicious escape from the daily grind.

The Holy Trinity: Skewer, Batter, and Sauce

The true magic of excellent kushikatsu lies in the ideal harmony of three essential components. First is the ingredient on the skewer. Timeless favorites remain popular: beef (gyu-katsu), fatty pork belly (buta-bara), chicken thigh (momo), and plump shrimp (ebi). Yet the real joy comes from exploring a wide and sometimes unexpected range. Quail eggs (uzura) become creamy bites inside a crunchy shell. Slices of lotus root (renkon) bring an earthy sweetness and delightful texture. Fried onion chunks (tamanegi) turn incredibly sweet and soft. More adventurous picks might include gooey Camembert cheese, chewy rice cakes (mochi), or even deep-fried ginger (beni shoga), which offers a sharp, palate-cleansing zing. The ingredient’s quality is crucial; it must be fresh enough to shine through its fried coating.

Next is the batter and panko. Each shop fiercely guards its secrets here. The batter is typically a thin mixture of flour, egg, and water, designed to act as a light adhesive rather than a heavy, doughy layer. The panko, or Japanese breadcrumbs, are vital for the signature texture. They are flakier and lighter than Western breadcrumbs, absorbing less oil and creating a shatteringly crisp crust that never feels greasy. The frying oil is usually a blend of vegetable and animal fats, kept meticulously clean and maintained at the ideal temperature to ensure each skewer cooks quickly and evenly, sealing in the ingredient’s moisture and flavor.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, comes the sauce. This is not the thick, sweet tonkatsu sauce found elsewhere. Shinsekai’s kushikatsu sauce is thinner, darker, and more savory, often featuring a complex blend of soy sauce, Worcestershire sauce, fruit purees, and spices. It is tangy, slightly sweet, and deeply umami, crafted to cut through the richness of the fried food without overpowering it. The sauce embodies the soul of the experience and is governed by the most important rule in the kushikatsu world.

The Unspoken Law: No Double Dipping

If there is one piece of etiquette to learn before entering a kushikatsu joint, it is this: `二度漬け禁止` (nidozuke kinshi), meaning “No double-dipping.” This rule is absolute and universally respected. Kushikatsu restaurants in Shinsekai traditionally serve their sauce in large, stainless-steel communal trays placed on the counter or table. Each diner dips a freshly fried skewer into the sauce once—only once—before taking the first bite. Once your lips have touched the skewer, it must never, under any circumstances, return to the shared sauce pot. This is a fundamental hygiene practice, a social contract that ensures everyone can safely enjoy the communal experience. The rule is prominently posted, and breaking it is considered a serious faux pas, inviting stern looks from staff and fellow diners. But what if you want more sauce midway through your skewer? Here, the third element of the kushikatsu ritual comes into play.

Cabbage: More Than Just a Garnish

Alongside the skewers and sauce pot, you will always receive a small bowl or plate of raw, crunchy cabbage wedges. This is not just a side or palate cleanser, though it serves those purposes well. The cabbage is your tool, your secret weapon for adding more sauce. If your skewer needs an extra splash of flavor after the first bite, simply take a clean piece of cabbage, dip it into the sauce, and use it as an edible spoon to drizzle the sauce onto your kushikatsu. This clever method respects the no-double-dipping rule while ensuring your food is perfectly sauced to your taste. The crisp, refreshing cabbage also provides a wonderful textural contrast to the fried skewers, cutting through the richness and preparing your palate for the next delicious bite.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Janjan Yokocho and Beyond

Dobutsuen-mae Station serves as a gateway, and just a short walk from its exit is Janjan Yokocho, the most famous and atmospheric covered shopping arcade in Shinsekai. The name itself is onomatopoeic, said to originate from the constant “janjan” strumming of shamisen that once attracted customers to the area’s many eateries and game parlors. Today, the sound of shamisen has been replaced by the sizzle of fryers, cheerful vendor shouts, and patrons’ chatter, but the vibrant, bustling energy remains. This narrow, 180-meter-long alley is the pulsating heart of Shinsekai’s kushikatsu scene, offering a sensory overload in the best possible way. The air is a heady blend of frying oil, savory sauce, and stale beer. On both sides, the lane is lined with a dense patchwork of tiny restaurants, standing bars (tachi-nomi), and shogi (Japanese chess) clubs where elderly men hunch over their boards in deep concentration.

Walking down Janjan Yokocho feels like stepping back in time. The establishments are small and cramped, often with just a single counter separating customers from the chef. Many have no seats at all, requiring diners to stand shoulder-to-shoulder, fostering a convivial, communal atmosphere. The decor is simple and unadorned: handwritten menus pasted on walls, well-worn wooden counters, and aged beer brand posters yellowed by time. Here, you’ll find some of the oldest and most beloved kushikatsu joints, places that have honed their craft for generations. Names like Daruma, often credited as one of the originators, have become institutions with multiple branches and lines of eager tourists stretching out the door. Yet, for every famous name, dozens of smaller family-run spots offer an equally, if not more, authentic experience.

Choosing where to eat can be overwhelming. A good strategy for first-timers is to simply wander and observe. Look for places busy with locals. A queue is often a positive sign, but don’t overlook smaller, quieter spots where you might enjoy a more personal interaction with the chef. Peek inside; if the atmosphere looks welcoming, give it a try. Most places display plastic food models or have picture menus, making ordering relatively easy even without speaking Japanese. A typical order begins with a beer (nama biru) and a plate of doteyaki, a slow-cooked beef tendon stew in a rich miso and soy broth, perfect as an appetizer while you wait for your first batch of freshly fried skewers. Don’t hesitate to try a standing bar. Though it may seem intimidating, the experience is quintessentially Osakan. Simply find a spot at the counter, order a drink and a few skewers, and enjoy the lively ambiance. The turnover is quick, making it a great way to sample several places in one evening.

The Sentinel of Naniwa: Tsutenkaku Tower’s Enduring Gaze

Dominating the entire district and visible from nearly every street corner is the Tsutenkaku Tower, the unmistakable emblem of Shinsekai. Its name means “Tower Reaching Heaven,” and although its current height of 103 meters is modest compared to modern skyscrapers, its cultural significance is immense. The present tower is actually the second version. The original, built in 1912 and inspired by the Eiffel Tower, was a source of great local pride. After it was dismantled during World War II, the community, eager to restore their cherished landmark, successfully advocated for its reconstruction. The new tower, designed by the same architect involved with Tokyo Tower, was completed in 1956 and swiftly regained its place as the neighborhood’s centerpiece.

Riding the elevator up to the observation decks is a must-do for any visitor. The ride itself feels like a performance, with elevators dimming and displaying celestial light shows during the ascent. From the top, you are treated to a 360-degree panoramic view of Osaka. In the distance, you can spot the modern skyscrapers of Umeda, the sprawling Tennoji Park and Zoo nearby, and directly below, the lively, colorful grid of Shinsekai. This vantage point offers a unique perspective, allowing you to appreciate the district’s compact, human scale in contrast to the vast urban sprawl around it.

The tower’s best-known resident stands on the main observation floor: a golden, grinning statue of Billiken. This quirky, elf-like figure is not a traditional Japanese god. It was created by American art teacher Florence Pretz, who said the image came to her in a dream. A version of the statue was installed in the original Luna Park and became an instant favorite. When the park closed, the statue vanished, but its memory endured. A new wooden Billiken was carved and placed in the rebuilt Tsutenkaku, where it has remained ever since, known as “The God of Things as They Ought to Be.” Legend has it that rubbing the soles of his feet brings good luck, and visitors are constantly doing so, leaving his feet smooth and shiny from decades of hopeful touch. Billiken perfectly captures the spirit of Shinsekai: a bit quirky, somewhat out of place, yet beloved and deeply rooted in the local culture.

Beyond the Fryer: Soaking in the Shinsekai Experience

While kushikatsu is undoubtedly the highlight, the Shinsekai experience encompasses much more than just food. The entire neighborhood serves as a playground of retro charm and distinctive attractions that can easily occupy an entire afternoon and evening. The streets resemble a living museum of mid-20th century Japanese pop culture. Enormous, three-dimensional fugu (pufferfish) lanterns hang above restaurants, their paper skins glowing eerily. Traditional arcades, with names such as “Kasuga Gorakujo,” invite you in with the clatter of pachinko balls and the tinny tunes of vintage video games. Unlike the modern, brightly lit arcades of Shinjuku or Akihabara, these are darker, smokier spaces filled with games of skill and chance that have entertained generations of Osakans.

For a different form of entertainment, small independent movie theaters screen classic Japanese films or niche B-movies, their hand-painted posters enhancing the nostalgic atmosphere. The shops are equally varied, offering everything from inexpensive souvenirs to old-fashioned snacks and vibrant Osakan-themed apparel. The area is also conveniently located next to two major attractions. As its name implies, Dobutsuen-mae Station sits directly in front of Tennoji Zoo, one of Japan’s oldest and most respected zoological parks, providing a peaceful, green retreat from Shinsekai’s urban buzz.

For a truly Japanese and quintessentially Osakan experience, a visit to Spa World is essential. This vast bathhouse complex, located just beside Shinsekai, spans multiple floors of relaxation. It features themed onsen (hot spring baths) separated by gender and rotated monthly. One floor is dedicated to a European zone, with baths inspired by ancient Rome, Greece, and Finland, while the other is an Asian zone offering baths that evoke the atmospheres of Persia, Bali, and Japan. Beyond the baths, the complex includes saunas, massage services, restaurants, and relaxation rooms, providing a surreal and deeply satisfying way to unwind after a day of exploring and enjoying kushikatsu.

A Traveler’s Guide to Shinsekai’s Rhythms

Approaching Shinsekai for the first time can feel somewhat overwhelming, but with a few practical tips, you can navigate its vibrant chaos like a local.

Getting There

Access is incredibly straightforward. The easiest way is via the Osaka Metro. Dobutsuen-mae Station is served by two major lines: the Midosuji Line (the primary north-south route connecting Umeda, Namba, and Tennoji) and the Sakaisuji Line. Alternatively, you can take the JR West lines. Shin-Imamiya Station on the Osaka Loop Line and the Yamatoji Line is just a short walk from the center of the district. This makes the area easily reachable from anywhere in Osaka and even nearby cities such as Kyoto and Nara.

When to Go

Shinsekai shows two distinct sides. By day, it’s quieter with a more local, neighborhood vibe. Residents go about their daily routines, and shogi clubs are active. Visiting Tsutenkaku Tower during daylight hours is ideal to avoid large crowds and enjoy clear views of the city. However, the district truly comes alive after sunset. As dusk approaches, hundreds of neon signs and paper lanterns light up, casting a warm, electric glow over the streets. The kushikatsu restaurants fill quickly, and the mood becomes lively and festive. For the full Shinsekai experience, plan to arrive in the late afternoon, visit the tower, and then immerse yourself in the evening’s culinary delights.

Local Etiquette and Practicalities

Aside from the cardinal rule of no double-dipping, there are a few other customs to keep in mind. Many of the smaller, older eateries only accept cash, so it’s advisable to carry enough yen. When you finish eating, the bill is typically calculated at your seat. Simply signal the staff by saying “Okanjo, onegaishimasu” (Check, please). At standing bars, it’s considered polite to order at least one drink per person. Although the atmosphere is relaxed, these venues have a high turnover, so lingering for long periods after you’ve finished eating and drinking, especially during busy times, is generally discouraged. Tipping is not customary in Japan.

Ordering Like a Pro

For your first round of kushikatsu, it’s best to start with a mix of familiar items to get a sense of the flavors. A typical starter set, or “moriawase,” may be offered, presenting a chef’s selection. If ordering a la carte, opt for a balanced variety: one or two meat skewers like beef and pork, a seafood choice such as shrimp or squid, and several vegetable skewers like onion, shiitake mushroom, and asparagus. This variety lets you appreciate different textures and tastes. Once you feel comfortable, try something new. Staff are usually happy to recommend dishes if you ask for the “osusume.”

Shinsekai is more than just a dining destination. It is a vibrant, living piece of history, a bold celebration of a past that refuses to fade away. This district overwhelms the senses with its bright lights, savory aromas, and lively sounds. Visiting there connects you with an authentic, unpolished side of Osaka, full of heart. It’s a reminder that the most memorable travel experiences are often found not in pristine, polished environments, but in places with grit, character, and stories to tell. So come hungry and open-minded, find a spot at a well-worn counter, and get ready to dive—just once—into the delicious world of Shinsekai.