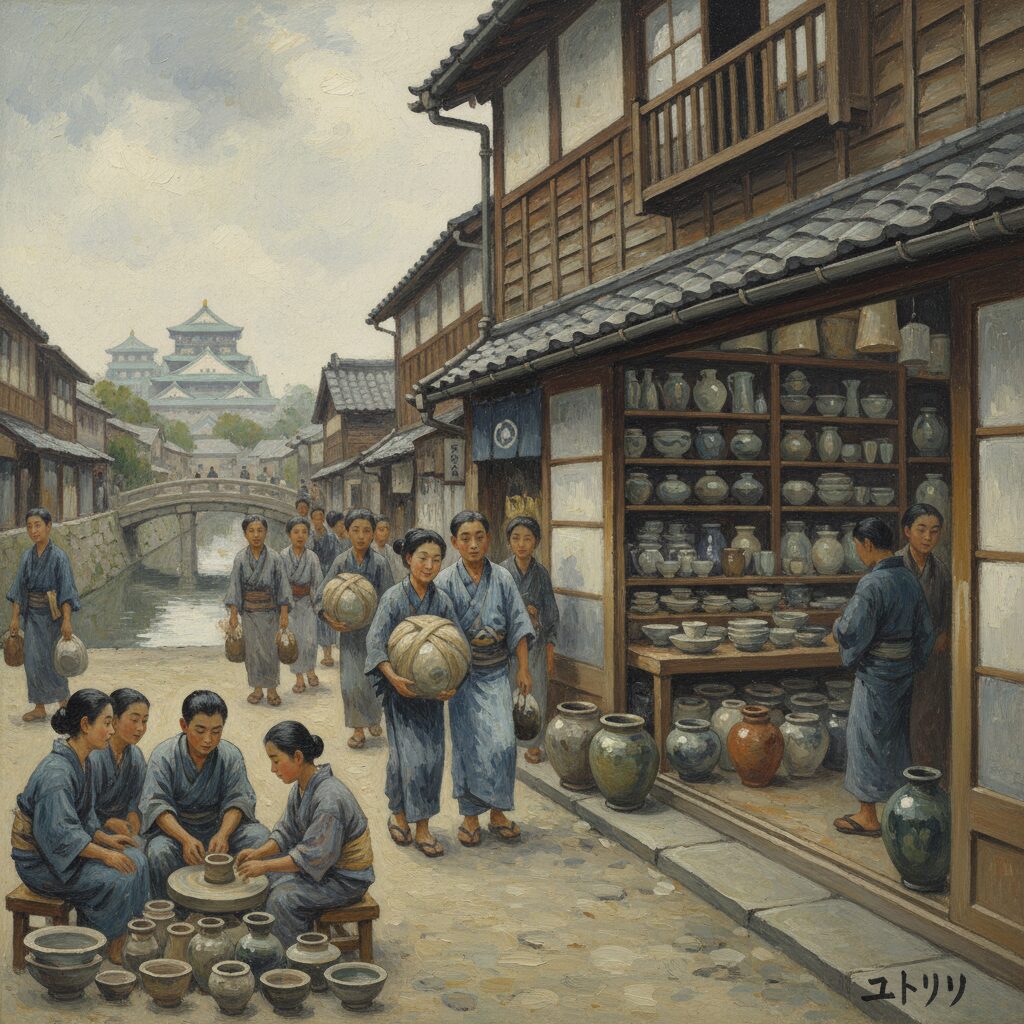

In the heart of Osaka, a city that pulses with electric energy, there lies a sanctuary of profound tranquility. It’s a place where time slows, where the clamor of the streets fades into a reverent hush, and where light itself seems to pay homage to the beauty it illuminates. This is The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, an institution nestled on the verdant island of Nakanoshima, floating between the Dojima and Tosabori rivers. It’s more than just a museum; it’s the permanent home of a story, a drama of passion, collapse, and miraculous rescue. At its core is the Ataka Collection, a trove of Chinese and Korean ceramics so exquisite, so perfect in its curation, that it is considered one of the most important of its kind anywhere on the globe. To step inside is to step into the mind of a master collector and to witness a legacy saved for the world by the spirit of Osaka. This isn’t just about viewing pottery; it’s about feeling the soul of the clay, understanding the vision of the artist, and appreciating the centuries-long journey these objects have taken to arrive in this peaceful haven. It’s a place for quiet reflection, a counterpoint to the city’s vibrant rhythm, offering a deep, resonant beauty that stays with you long after you’ve left.

After experiencing the profound tranquility of the Ataka Collection, you might find yourself drawn to explore the vibrant energy of Osaka’s nightlife, starting with the hidden cocktail bars in Kitashinchi.

A Passion Forged in Fire: The Vision of Eiichi Ataka

To grasp the essence of The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, one must first understand the man whose unique passion created its central collection: Eiichi Ataka. He was not merely a wealthy industrialist purchasing art; he was a genuine connoisseur, whose life was closely tied to the pursuit of ceramic beauty. Born into the family that managed a major trading company, Ataka & Co., Ltd., he rose to become its chairman, a key figure in Japan’s post-war economic boom. Yet beneath the polished exterior of a corporate leader lay the heart of a poet and ceramic scholar.

Ataka’s journey into collecting was far from a casual pastime. It was a profound intellectual and emotional endeavor. He began collecting in the 1950s, a period when Japan was rebuilding and reshaping its cultural identity. While many focused on traditionally celebrated Japanese arts, Ataka’s attention turned to Asia, especially the masterworks of China and Korea. He possessed what is often described as a “collector’s eye”—an almost mystical talent for discerning not only authenticity and technical excellence but also the life force and inner spirit of a piece. He sought ceramics that resonated with him, works that conveyed warmth, quiet dignity, or dynamic energy. He would spend hours studying a single bowl or vase, reflecting on its shape, the texture of its glaze, and the history it narrated through time.

His approach was unconventional. He did not simply aim to acquire famous or representative works from every major kiln or dynasty, as if ticking off a checklist. Rather, he built his collection organically, guided by his own aesthetic sensibility. Ataka believed that the finest ceramics possessed a beauty that transcended cultural and historical divides. He once said he wanted to create a collection where each piece could stand alone as a world-class masterpiece. This uncompromising vision drove him to pursue pieces with relentless passion, collaborating with top art dealers both in Japan and abroad. He fostered close ties with scholars and experts, continually expanding and refining his knowledge. The Ataka Collection was not an accumulation but a carefully, lovingly, and meticulously curated treasure shaped by one man’s steadfast vision over twenty-five years.

This endeavor was financed both by his personal wealth and, importantly, by his company’s resources. In the era of rapid economic growth, it was common for large corporations to assemble art collections as assets and symbols of prestige. Yet, the scale and personal devotion behind Ataka’s collecting were exceptional. He invested vast sums to acquire nearly a thousand pieces, each meeting his rigorous standards. This collection became his life’s work—a tribute to a deep love for the potter’s wheel and the transformative magic of the kiln.

The Precipice and the Pledge: A Legacy in Peril

The story of the Ataka Collection took a dramatic turn in the mid-1970s. The global oil crisis sent shockwaves through the world economy, and Japan was severely affected. Ataka & Co., once a symbol of Japan’s industrial strength, found itself in serious financial trouble and, in 1977, collapsed in one of the largest corporate bankruptcies in post-war Japanese history. The company’s assets were slated for liquidation to cover its enormous debts, including the priceless ceramic collection that Eiichi Ataka had spent his life assembling.

The news sent shockwaves through Japan’s cultural community. The collection was in immediate danger of being broken apart. Individual pieces were likely to be sold to the highest bidders, scattered among private collectors worldwide, and lost to the public forever. This would have been an irreplaceable cultural loss. The possibility of masterpieces like the famed Yohen Tenmoku tea bowl leaving Japan sparked widespread public and media outrage. Scholars, art critics, and ordinary citizens appealed for a solution to keep the collection intact and in Japan.

This crisis became a defining moment for Osaka’s civic and corporate identity. The City of Osaka wanted to preserve this cultural treasure but lacked the funds to acquire it outright. At that point, another corporate giant entered the story. A consortium of 21 companies from the Sumitomo Group, a conglomerate with deep historical ties to Osaka, united in an unprecedented act of cultural philanthropy. Led by Sumitomo Bank, the group negotiated to purchase the entire Ataka Collection for a substantial sum.

Their motivation was not financial gain but a profound sense of civic responsibility and recognition of the collection’s immense cultural significance. They understood this was more than a corporate asset; it was part of Japan’s, and indeed the world’s, cultural heritage. They pledged to donate the entire collection to the City of Osaka on one condition: that the city build a museum worthy of housing it, a place where it could be preserved, studied, and shared with the public for generations to come. This was the miracle. From the ruins of a corporate collapse, a public treasure was born. The city accepted, and plans for The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, were set in motion—a testament to the collective belief that art and culture are vital to the life of a city.

A Vessel of Light: The Museum’s Revolutionary Design

True to its commitment, the City of Osaka built a museum that stands as a masterpiece of design itself, crafted specifically to enhance the appreciation of its ceramic collection. Opened in 1982, the museum’s architecture exemplifies understated elegance and innovative vision. The building does not demand attention; instead, it gently guides focus towards the treasures it houses. Architect Kiyonori Kikutake and his team created a viewing experience that was groundbreaking at the time and remains a standard in museum design today.

The most striking feature is the ingenious use of natural light. As someone who spends considerable time outdoors, I deeply appreciate how sunlight reveals the true essence of a landscape. The museum’s designers embraced this concept fully, knowing that the subtle hues, deep luster, and delicate textures of ceramic glazes are best showcased not by harsh artificial spotlights but by the soft, diffused radiance of natural light. The main exhibition galleries feature large windows overlooking the park and river, yet the light is filtered and softened to eliminate harmful ultraviolet rays and direct glare. This ambient light fills the space, allowing the ceramics to breathe. The ethereal blue-green glaze of a celadon vase appears to shift and shimmer with passing clouds, while the deep, dark glaze of a Tenmoku bowl reveals its hidden depths, fostering an intimate, almost spiritual bond between viewer and object.

Inside the galleries, the atmosphere is calm and serene. Muted walls, soaring ceilings, and spacious layouts encourage unhurried reflection. Another clever innovation is the design of the display cases. Many key pieces are housed in slowly rotating vitrines, allowing visitors to stand still and watch an object complete a 360-degree turn, revealing every curve and detail without needing to walk around it. This simple, elegant solution enables a thorough and immersive appreciation of the object’s three-dimensional form.

Benches are thoughtfully positioned throughout the galleries, inviting visitors to sit and linger with a specific piece. This is not a museum designed for swift walkthroughs but for slow, mindful observation. The quiet hum of the climate control system is the only sound, creating a meditative environment where one can truly lose themselves in the art. The entire building serves as a vessel, meticulously crafted to hold and present these delicate objects in the most beautiful and respectful manner possible.

The Crown Jewels: Timeless Masterpieces of Clay and Glaze

While the entire Ataka Collection is stunning, a few standout pieces represent the pinnacle of ceramic artistry, attracting visitors from around the world. To stand before them is to experience the weight of history and the pinnacle of human creativity.

At the forefront is the “Yohen Tenmoku” Tea Bowl, designated a National Treasure of Japan. Viewing it is an unforgettable experience. The bowl is modest in size, fitting comfortably in cupped hands. Its shape is simple, rustic, yet flawless. But its interior is nothing short of a universe. The term “Yohen,” meaning “kiln change” or “glowing embers,” refers to the unpredictable and almost miraculous patterns formed during firing. Against a deep, glossy black glaze, iridescent spots of varying sizes shimmer with cosmic hues of blue, purple, and silver, resembling a star-filled galaxy—a celestial phenomenon captured in clay. Created during China’s Southern Song dynasty (12th-13th century), the exact method of its creation remains a mystery, enhancing its allure. Only a few genuine Yohen Tenmoku bowls exist worldwide, all housed in Japan. This single piece embodies Eiichi Ataka’s entire philosophy: an object of profound, unique beauty that transcends function to become pure art.

Equally captivating is the Celadon Vase with Inlaid Cranes and Clouds from Korea’s Goryeo dynasty (12th century). This piece exudes pure elegance and serenity. Its form is graceful, with a gently swelling body and a long, slender neck. It is coated in a calm, jade-like blue-green glaze, a hue so treasured it is often called “Goryeo celadon green.” Yet the delicate inlaid decoration truly distinguishes it. Using the sophisticated “sanggam” technique, the potter carved fine lines into the clay body, filled them with white and black slip, then applied the celadon glaze over the top. The result is a design of ethereal white cranes flying among stylized clouds, appearing to float just beneath the glaze’s glassy surface. The cranes, symbols of longevity and good fortune, are rendered with exquisite delicacy. The piece reflects the refined aesthetics of the Goryeo aristocracy and a profound connection to nature and Buddhist ideals of peace.

Providing a striking contrast is the large Blue-and-White Jar with Fish and Algae Design from China’s Yuan dynasty (14th century). Where the celadon vase is quiet and contemplative, this jar bursts with life and energy. It marks a pivotal moment in ceramic history—the perfection of cobalt blue painting under a clear glaze. The painting is masterful and dynamic; four different species of fish swim vigorously among lotus pads and waving waterweeds. The artist’s brushwork is confident and fluid, capturing the movement and teeming life of a pond. The vibrant cobalt blue against the pristine white porcelain heralded a revolutionary aesthetic that would dominate the global ceramic market for centuries. This jar is a powerful statement of artistic innovation and vitality.

Exploring the Island Oasis of Nakanoshima

The experience of visiting the museum is wonderfully enhanced by its location. Nakanoshima is a narrow island, about 3 kilometers long, that serves as Osaka’s cultural and administrative center. It is an urban park and a green oasis, providing a welcome break from the dense cityscape. Before or after your visit, take some time to explore this charming area.

A short walk east of the museum leads you to the Nakanoshima Rose Garden. In spring (mid-May) and autumn (mid-October), the garden bursts with color and fragrance, as thousands of rose bushes bloom. It’s an ideal spot to sit on a bench and take in views of the river along with the mix of modern and historic architecture. The contrast between the flowers’ natural beauty and the urban skyline is truly emblematic of Osaka.

At the eastern end of the island stands the Osaka City Central Public Hall, a magnificent Neo-Renaissance building featuring a striking red-brick facade and a bronze dome. Completed in 1918, it is a cherished city landmark and a beautiful example of architectural history. It sits beside the Osaka Prefectural Nakanoshima Library, another grand stone building from the early 20th century. Walking around here feels like stepping back into a different era of the city’s history.

The riverside promenades are perfect for a leisurely walk. You can watch tourist boats glide past and enjoy the refreshing breeze from the water. Along the river, several stylish cafes and restaurants, many with outdoor terraces, offer excellent places to relax with coffee or a meal. As someone who loves the outdoors, I find Nakanoshima to be the perfect urban equivalent of a gentle trail—a well-defined path with beautiful scenery, fresh air, and moments of quiet discovery.

A First-Timer’s Guide to a Perfect Visit

Planning your trip to The Museum of Oriental Ceramics is straightforward, but a few tips can help make your visit even more memorable.

Getting there is convenient. The museum is just a short walk from multiple train and subway stations. Yodoyabashi Station (Midosuji Line) and Kitahama Station (Sakaisuji Line) lie to the south, across the Tosabori River, while Oebashi Station on the Keihan Nakanoshima Line is even nearer. The walk from any of these stations is enjoyable, taking you over a bridge with beautiful views of the island.

The museum generally opens from 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM, with the last admission at 4:30 PM. It is typically closed on Mondays and during the New Year holidays, but it’s always best to check the official website for updated hours, exhibition details, and admission fees before your visit.

My most important advice is to allow enough time. This is not a place to be rushed. Set aside at least two hours to fully appreciate the main collection. If possible, visit on a weekday morning when crowds are smaller, providing a more intimate and reflective experience. Find a bench in front of a piece that draws your attention and spend some time with it. Observe the details, the way light plays on its surface, and the emotions it stirs.

Don’t forget to explore beyond the renowned Ataka Collection. The museum also features the exquisite Rhee Byung-chang collection of Korean ceramics and hosts special exhibitions showcasing both historical and contemporary works, offering a wider perspective on ceramic arts. The museum shop is excellent as well, with beautiful books, postcards, and unique ceramic-inspired gifts.

Lastly, embrace the calmness of the space. Let the peaceful atmosphere envelop you. In a bustling city like Osaka, the museum provides a rare and valuable chance to slow down, look closely, and connect with objects that represent centuries of human creativity and timeless, universal beauty.

A Confluence of Passion and Place

A visit to The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, is an immersion into a remarkable narrative. It tells the story of Eiichi Ataka’s unique and passionate vision. It recounts how a city and its corporate citizens united to rescue a cultural legacy from the verge of disappearance. It also illustrates how expert design can craft the ideal setting to experience art. The collection itself stands as a silent tribute to the lasting power of beauty, a dialogue spanning centuries between the potter, the collector, and the viewer. Here, on this tranquil island amid one of Japan’s most vibrant cities, you will discover a profound sense of calm and a deep appreciation for the quiet masterpieces that, against all odds, have found their permanent home. This is a place that will deepen your understanding of art and leave you with enduring inspiration.