Step out of the sleek, subterranean labyrinth of Umeda Station, and you emerge into a world of polished chrome, soaring glass towers, and relentless, forward-marching energy. This is Osaka’s commercial heart, a dazzling nexus of capital and consumerism. But take a ten-minute walk—a mere handful of city blocks northeast—and the symphony of the metropolis fades. The air changes. The rhythm slows to a gentle, shuffling beat. You’ve crossed an invisible threshold into Nakazakicho, a neighborhood that feels less like a place and more like a beautifully preserved memory. Here, time hasn’t stopped, but it certainly has taken a deep, contemplative breath. This is Osaka’s bohemian soul, a living museum of Showa-era charm and a vibrant canvas for modern creativity, where a rich life of style and culture doesn’t demand a wealthy patron. It’s a pocket of resistance against the city’s relentless modernization, a place where the past is not just remembered but worn, sipped, and lived in every day. For the foreigner seeking the true pulse of Osaka’s counter-culture, for the resident tired of the high-street hustle, Nakazakicho offers an invitation to get wonderfully, blissfully lost in a labyrinth of stories, all waiting to be discovered on a dime.

To fully immerse yourself in this retro atmosphere, consider exploring more about Nakazakicho’s hidden retro paradise.

The Whispering Alleys: A Symphony of Imperfection

To truly understand Nakazakicho, you must first grasp its architecture, which is fundamentally an architecture of survival. While World War II bombs devastated the surrounding areas, this small enclave was miraculously preserved. The result is a dense maze of narrow, winding alleys flanked by two-story wooden townhouses called nagaya. These are not grand edifices; rather, they are modest, human-scale homes designed for practicality and community. Their wooden exteriors have been weathered and etched by decades of sun and rain, their tiled roofs slightly uneven, and their sliding doors gently rattling in the breeze. This forms the backdrop against which the neighborhood’s identity is drawn. Walking here is a sensory experience. Your shoulder might brush against a wall cloaked in tangled ivy, its green tendrils creeping over a faded advertisement from days long gone. Your path may be diverted by a cluster of mismatched potted plants—a miniature jungle of aloe, ferns, and tiny bonsai thriving on a concrete stoop. The air carries the scent of damp earth after a light rain, the faint aroma of roasting coffee beans from a hidden café, and the fresh smell of laundry hanging from a second-story balcony. There is a profound sense of wabi-sabi here, the Japanese aesthetic valuing beauty in imperfection and impermanence. Nothing is immaculate, and that is precisely the point. The chipped paint, rusted mailboxes, crooked window frames—they all narrate a story of resilience and continuity. This atmosphere stands in stark, almost defiant contrast to the sterile perfection of the Umeda skyscrapers looming on the horizon, a constant reminder of the differing worlds coexisting just meters apart. The silence in these alleys is deep, broken only by the chime of a bicycle bell, the distant rumble of the elevated train line, or the soft murmur of conversation drifting from an open doorway. It is a place that invites you to slow down and notice the small details: a ceramic cat peeking from a windowsill, a tiny, hand-painted sign for a shop that feels more like a secret clubhouse, the intricate patterns of light and shadow cast by overhead electrical wires. This is the essence of the place, a quiet rebellion spoken in the language of wood, tile, and time.

The Thrill of the Hunt: Diving into Nakazakicho’s Vintage Universe

At the heart of Nakazakicho’s bohemian economy lies its myriad furugi-ya, or second-hand clothing shops. This experience is more than just shopping; it’s urban archaeology—a treasure hunt through the wardrobes of bygone generations. The astonishing variety is overwhelming, and each store exudes a distinct personality, often mirroring the passion of its owner. Forget the sterile, brightly lit chain stores downtown. Here, retail becomes an art form, an intimate exchange of stories woven into fabric. You might stumble upon a place like ‘Yesterday’s Parade’ (a name I’ve imagined to capture its essence), a tiny shop brimming with American vintage from the 1960s and 70s. The air inside carries the scent of aged denim and leather. Racks overflow with perfectly faded Levi’s, psychedelic rock band tees as delicate as whispers, and suede jackets adorned with impossibly long fringe. The owner, a man with greying ponytail and encyclopedic rock history knowledge, might share the story behind a jacket—who wore it, which concert it accompanied. Prices are reasonable, but the true value lies in authenticity—the feeling of connecting with a specific cultural moment.

Turn a corner, and you could find yourself in ‘Showa Romance,’ a space celebrating the delicate, feminine fashions of mid-century Japan. The atmosphere changes completely. Soft light filters through paper screen windows, illuminating mannequins dressed in elegant A-line dresses with floral prints and Peter Pan collars. Racks hold silk blouses, wool coats with classic tailoring, and tiny beaded handbags evoking a more formal, graceful era. The proprietress, moving with quiet elegance, meticulously restores each piece, mending loose seams and polishing buttons. She views herself not as a mere shopkeeper but as a guardian of history, preserving the sartorial dreams of post-war Japanese women. For a few thousand yen, you can own a piece of that history—a garment crafted with a level of artistry nearly impossible to find in today’s fast-fashion world.

Then there are the more eclectic, chaotic shops, those that feel like a rummager’s paradise. Imagine ‘The Magpie’s Nest,’ where clothes are heaped in bins and sold by weight. The thrill lies in the hunt. You might spend an hour sifting through mountains of fabric, your hands brushing wool, cotton, silk, and polyester. Your patience could be rewarded with anything: a forgotten designer piece from the 80s, a quirky hand-knitted sweater, a perfectly worn flannel shirt. Prices are minimal, often just a few hundred yen. This is the ultimate democratization of style, proving that a sharp eye and some effort outweigh a fat wallet. These shops embody the Japanese concept of mottainai, a profound aversion to waste—nothing is discarded; everything has a chance at a second life, a new story. Budgeting here isn’t about limits; it’s about the joy of discovery, crafting a wardrobe that’s unique, sustainable, and deeply personal. You leave not just with clothes, but with artifacts, each carrying its own silent history. This is the true currency of Nakazakicho’s bohemian lifestyle—individuality over mass production, story over status.

The Art of the Find: A Closer Look at Vintage Culture

Delving deeper into Nakazakicho’s furugi subculture reveals layers of specialization that are utterly captivating. It’s a world that rewards curiosity. Beyond general vintage stores, you’ll find hyper-focused boutiques catering to highly specific tastes. Picture a shop devoted solely to military surplus. The interior is stark and utilitarian, filled with the scent of canvas and oil. The owner, likely a history enthusiast, might spend an hour explaining the origins of a French M-47 field jacket, highlighting subtle differences in fabric and stitching across production years. Here, you’re not just buying a coat; you’re investing in functional design history—a garment built to endure, its durability a statement in itself. Prices may be a bit higher than average vintage, but you’re paying for timeless quality.

Elsewhere, an entire store might focus on remade or upcycled clothing. This is where Nakazakicho’s creativity truly shines. Local designers repurpose forgotten garments—kimono with minor flaws, oversized men’s suits, old work uniforms—deconstructing them into entirely new, avant-garde pieces. A bolt of vivid silk from a Showa-era kimono might become the back panel of a modern denim jacket. Two distinct flannel shirts could be merged to create an asymmetrical design. These one-of-a-kind creations represent sustainable fashion at its peak, blending traditional Japanese textiles with contemporary silhouettes. They are wearable art, and while pricier, they directly support the neighborhood’s vibrant creative community.

For the truly budget-conscious, timing and observation are key. Many shops have seasonal sales or unannounced clear-outs. Following favorite stores on social media is essential for modern thrifters. A sudden post might announce a ‘tsumehodai’ event, where you can fill a bag for a flat rate. These events are lively, fun, and an excellent way to build a versatile wardrobe without overspending. It’s a game of speed, strategy, and luck. The best advice for first-timers is to come without a specific goal. Don’t hunt for a “blue coat.” Instead, stay open—let a color, texture, or pattern catch your eye. Try on pieces you’d never normally choose. Nakazakicho’s vintage scene works its magic by helping you uncover new sides of your style, piecing together your identity from beautiful fragments of the past.

The Cafe as Sanctuary: Sipping Slowly in a Fast World

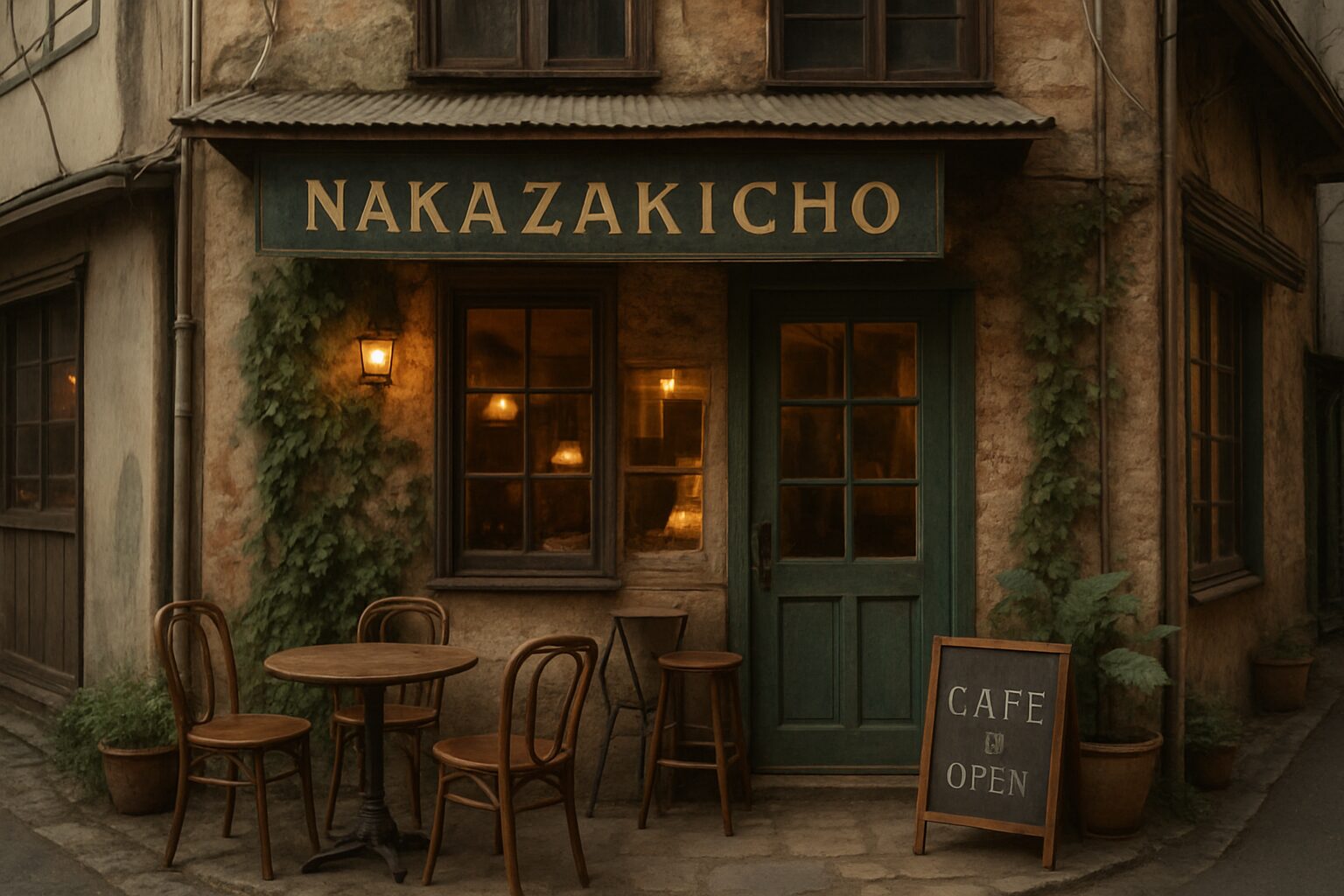

If vintage shops are Nakazakicho’s beating heart, then its cafes are its soul. These are not the sterile, efficient coffee chains of the business district, designed for a quick caffeine fix and a swift exit. Nakazakicho’s cafes serve as destinations in their own right—sanctuaries meant for lingering, reading, dreaming, and connecting. Many reside within the same nagaya as the shops, their interiors lovingly renovated by their owners. Stepping inside feels like being invited into someone’s home. The floors might be worn tatami mats or dark, polished wood. The furniture is a carefully curated mix of mismatched vintage pieces: a comfortable, slightly sagging velvet armchair in one corner, a sturdy wooden school desk in another. Soft, warm lighting casts a gentle glow on walls that often double as gallery space for local artists.

Picture a place like ‘Cafe Salon,’ tucked away down an alley so narrow you might miss it if you blink. You slide open a creaky wooden door and are greeted by the rich, complex aroma of freshly ground coffee and old books. The owner, a quiet woman in her fifties, runs the entire café on her own. She uses a siphon coffee maker—a beautiful, theatrical brewing method involving glass globes, open flames, and a bit of chemistry. The process is slow and deliberate, a small performance that encourages you to pause and appreciate the craft. Your coffee arrives in a delicate, patterned porcelain cup that doesn’t match its saucer. Alongside, you might order a slice of her homemade cheesecake—dense, creamy, and not overly sweet. The only soundtrack is the gentle hiss of the siphon and soft jazz from a vintage record player. Patrons sit alone, absorbed in novels, or whisper quietly in pairs, their conversations swallowed by the wooden beams and paper screens. An hour here feels like a miniature retreat, a mental reset, and the price for such profound peace is little more than a few hundred yen for a cup of coffee.

Then there are the more quirky spots. You might discover a ‘Cat Cafe,’ but one that feels less like a theme park and more like a cozy living room inhabited by a dozen rescued felines. The entrance fee helps support their care, and you can spend an afternoon with a purring cat on your lap and a warm mug of tea in your hands. Or perhaps you’ll find a ‘Gallery Cafe,’ where the entire space is transformed monthly to showcase a new photographer, painter, or sculptor. The menu is simple—a few teas, coffees, and perhaps some cookies—because the focus is on the art. It’s a place for quiet contemplation and conversation, a hub where artists and art lovers connect in an unpretentious setting. The business model is not about rapid turnover; it’s about fostering community. This embodies the bohemian budget. You’re not just paying for a product; you’re contributing to the cultural fabric of the neighborhood. You pay for the privilege of occupying a beautiful, inspiring space for a while. These cafes offer a powerful antidote to the loneliness of city life. They are ‘third places,’ somewhere between home and work, where belonging comes without pressure or expectation. They prove that the most valuable things—comfort, community, and a moment of peace—often come with the smallest price tags.

A Menu of Moments: The Diversity of Cafe Experiences

Nakazakicho’s cafe culture is a rich tapestry, and exploring its nuances is one of the area’s greatest joys. The variety extends far beyond the usual coffee and tea offerings. One cafe may specialize in traditional Japanese sweets, or wagashi. Here, you might sample a delicate nerikiri shaped like a seasonal flower, its sweet bean paste filling a subtle counterpart to the bitter, frothy matcha it accompanies. This experience exemplifies Japanese aesthetics, where taste, texture, and visual presentation intertwine. It’s an affordable luxury, a refined moment that connects you to centuries of Japanese culinary tradition.

Another spot might focus on health and wellness, offering organic herbal teas, freshly squeezed juices, and vegan baked goods. The atmosphere is bright and airy, filled with plants and natural light. It’s a place to nourish both body and soul, a quiet venue for a healthy lunch set featuring brown rice, miso soup, and a variety of seasonal vegetable dishes. These lunch sets often rank among the best deals in the neighborhood, providing a full, nutritious meal for about a thousand yen. It’s a way to eat well while supporting small, independent businesses that emphasize quality ingredients and mindful preparation.

Don’t forget the classic kissaten. These traditional Japanese coffee shops, precursors to the modern cafe, exude a distinct retro, Showa-era vibe. Their decor typically includes dark wood paneling, velvet banquettes, and Tiffany-style lamps. The owners are often an older couple who have run the place for decades. The menu offers a nostalgic journey: thick slices of toast with butter and jam, “pizza toast” topped with cheese and green peppers, a creamy ‘melon soda’ float with a scoop of vanilla ice cream, and rich, dark-roast coffee. A kissaten is more than just a cafe; it’s a time capsule. It’s a place to read a newspaper, enjoy a quiet smoke (in designated areas), and watch the world leisurely pass by. The experience is deeply comforting and uniquely Japanese—a glimpse into the daily life of a previous generation. The cost is modest, but the cultural immersion is invaluable.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Practical Advice for the Urban Explorer

Reaching Nakazakicho is surprisingly straightforward. From the expansive, sprawling Osaka-Umeda Station complex, it’s only a 10-to-15-minute walk. The walk itself offers a striking contrast: you pass towering department stores and busy intersections, then almost suddenly turn a corner into a quiet residential street. The city noise fades away, and a journey into the past begins. Alternatively, for a quicker option, take the Osaka Metro Tanimachi Line one stop from Higashi-Umeda to Nakazakicho Station. Exiting through Exit 2 or 4 places you right in the midst of the action—or rather, the calm.

The best tip for your first visit is to ditch your map, or at least tuck it away for emergencies. The true charm of Nakazakicho lies in aimless wandering. Let curiosity lead you. Follow the alley that catches your eye. Peek into the shop with the quirky mannequin displayed in the window. The neighborhood is a compact, walkable grid, so getting lost isn’t really possible. Every mistaken turn offers a new discovery—a tiny shrine between two houses, a wall decorated with whimsical street art, a hidden café with just three tables. This is not a place to conquer with a checklist; it’s a place to soak in slowly.

A few local tips can help your exploration go smoothly. Though many places now accept credit cards, cash is still preferred, especially in smaller, owner-run shops and cafés. It’s smart to carry some yen. Also, pay attention to opening hours. Nakazakicho’s rhythm isn’t the typical 9-to-5 corporate schedule. Many shops open around noon or later and may close unpredictably on certain days. If there’s a must-visit store, check their Instagram or website ahead for the latest info. Finally, remember you’re walking through a living, breathing residential area. Be respectful to the residents in these charming homes. Keep your voice low, avoid blocking walkways, and be considerate when taking photos. The unique atmosphere you enjoy depends on maintaining this delicate balance between commerce and community.

The Soul of a City on a Shoestring

In a world that often feels increasingly uniform and costly, Nakazakicho stands as a powerful testament to the lasting value of authenticity, community, and creativity. It’s a neighborhood that demonstrates a fulfilling, stylish, and culturally rich lifestyle doesn’t have to be a luxury. It can be crafted from second-hand treasures, nurtured by simple cups of coffee, and supported by a community of passionate individuals who have chosen to build their own world in the shadows of the city. This is more than just a place to shop or dine; it’s a living philosophy. It reminds us that the most beautiful things in life often carry a bit of history, a touch of imperfection, and a great deal of soul. So come with an open mind and comfortable shoes. Come with a few yen in your pocket and some time to spare. Come and lose yourself in the whispering alleys of Nakazakicho. You might discover that the most precious thing you take away is a renewed sense of inspiration, the feeling that a beautiful life isn’t something you buy, but something you create, one vintage find and one quiet cup of coffee at a time.