There’s a certain kind of magic that settles over Osaka as dusk begins to bleed into the neon-soaked sky. The frantic energy of the day, the clatter of commerce, the rush of trains—it all starts to soften at the edges. It’s in these moments, when you peel away from the main thoroughfares and duck into the quiet, labyrinthine side streets, that you can find the true, steaming heart of the city. It’s a heart that beats behind a simple sliding door, under a gently swaying noren curtain, in a place known as the sentō, the neighborhood public bath. This isn’t just a place to get clean. In a city as wonderfully complex and layered as Osaka, the sentō is a living museum, a community center, and a sanctuary all rolled into one. It’s where generations collide, where the day’s worries are washed away in clouds of steam, and where the subtle, unwritten rules of Japanese society play out in a ritual of communal vulnerability. For anyone looking to connect with the genuine spirit of this city, to understand the rhythm of daily life beyond the tourist trails, taking the plunge into the world of the sentō is an essential, beautiful, and profoundly human experience. It’s a journey into the warm embrace of the neighborhood itself.

To fully appreciate this communal warmth, it helps to understand the famously open and friendly character of the city, which is often highlighted in discussions about Osaka’s unique friendliness compared to Tokyo.

The Heartbeat of the Neighborhood: More Than Just a Bath

Calling a sentō simply a bathhouse is like referring to a pub as just a place to drink—it completely misses the point. The sentō serves as the neighborhood’s living room, embodying the Japanese idea of hadaka no tsukiai, or “naked communion.” This intriguing concept implies that once you shed your clothes, uniforms, and markers of status or profession, what remains are just people—neighbors. In this shared space, a unique, more genuine form of communication flourishes. You notice it immediately upon entering the changing room, the datsuijo. An elderly woman could be chatting with a young mother as her toddler runs about, a group of university students might be laughing over their day, and a salaryman may quietly stretch after a long shift. There’s a warm, well-worn hum to the place. The air is dense not only with steam but also with the easy rhythm of local conversation, the Osaka-ben dialect singing in a melodic flow.

The atmosphere is an orchestra of simple, grounding sensations: the clatter of plastic washbowls on the tiled floor, the steady rush of water from the showers, and the deep, resonant voices echoing through the high-ceilinged bathing hall. The sweet, clean scent of soap blends with the mineral tang of hot water and, if you’re fortunate, the subtle, woody aroma of a cypress bath. Visually, the scene is a patchwork of details: rows of identical yellow kerorin buckets, named after a classic pain reliever brand; slightly faded posters on the walls promoting local businesses or cautioning against slips; and hefty, old-fashioned massage chairs tucked into a corner of the changing room that look as if they could launch you into orbit. It’s worlds apart from the polished perfection of a modern spa. It’s authentic, practical, and profoundly comforting. Here, you don’t just observe local life—you engage with it. You might receive a friendly, unsolicited tip from an obaachan (grandmother) on the proper way to scrub your back or share a silent, knowing nod with someone as you both soak in the blissfully hot water. These simple moments of connection are the true treasures of the sentō experience.

A Journey Through Time: The Soul and Story of Osaka’s Sentō

Every sentō is rich in history, reflecting a time when private bathrooms were a luxury rather than a standard feature. Their golden era flourished in the post-war decades, when these bathhouses played a crucial role, providing hygiene and a warm sanctuary for entire communities. They became neighborhood pillars, places where information was shared, friendships formed, and a collective identity strengthened. Many of Osaka’s older sentō still showcase the architectural features of that period. You might encounter one with a stunning karahafu gabled entrance and intricate carvings, a style called miyazukuri, which echoes the grandeur of a traditional Shinto shrine. This was intentional; the bathhouse was viewed as a sacred, temple-like space for the community—a palace of cleanliness and relaxation.

Inside, the most iconic element is often the mural, or penki-e, that dominates the wall above the main tubs. Traditionally, and somewhat intriguingly, the subject is almost always a majestic, snow-capped Mount Fuji. Why depict Fuji, a mountain hundreds of kilometers away, in the heart of Osaka? The tradition is believed to have originated in Tokyo, but Fuji became a symbol of classic Japanese beauty and grandeur, offering a calming, aspirational view for bathers. These magnificent murals are a fading art, with only a few master artists remaining in Japan who can create them. Gazing up at that vast, idealized landscape from the steamy water is a meditative experience, connecting you to generations of bathers who have done the same. The artistic detail extends to the floors and walls as well. Watch for beautiful kutani-yaki or arita-yaki tiles, often featuring colorful koi, flowers, or scenes from folklore. These details are more than decoration; they form part of a carefully designed environment meant to transport you away from the everyday. Although many sentō have sadly closed over the years, there is a hopeful revival underway. A new generation is rediscovering their appeal, with some older bathhouses being reimagined as “designer sentō,” blending retro charm with modern features like craft beer on tap or contemporary art installations, ensuring that this essential part of Osaka’s cultural heritage continues to grow and thrive.

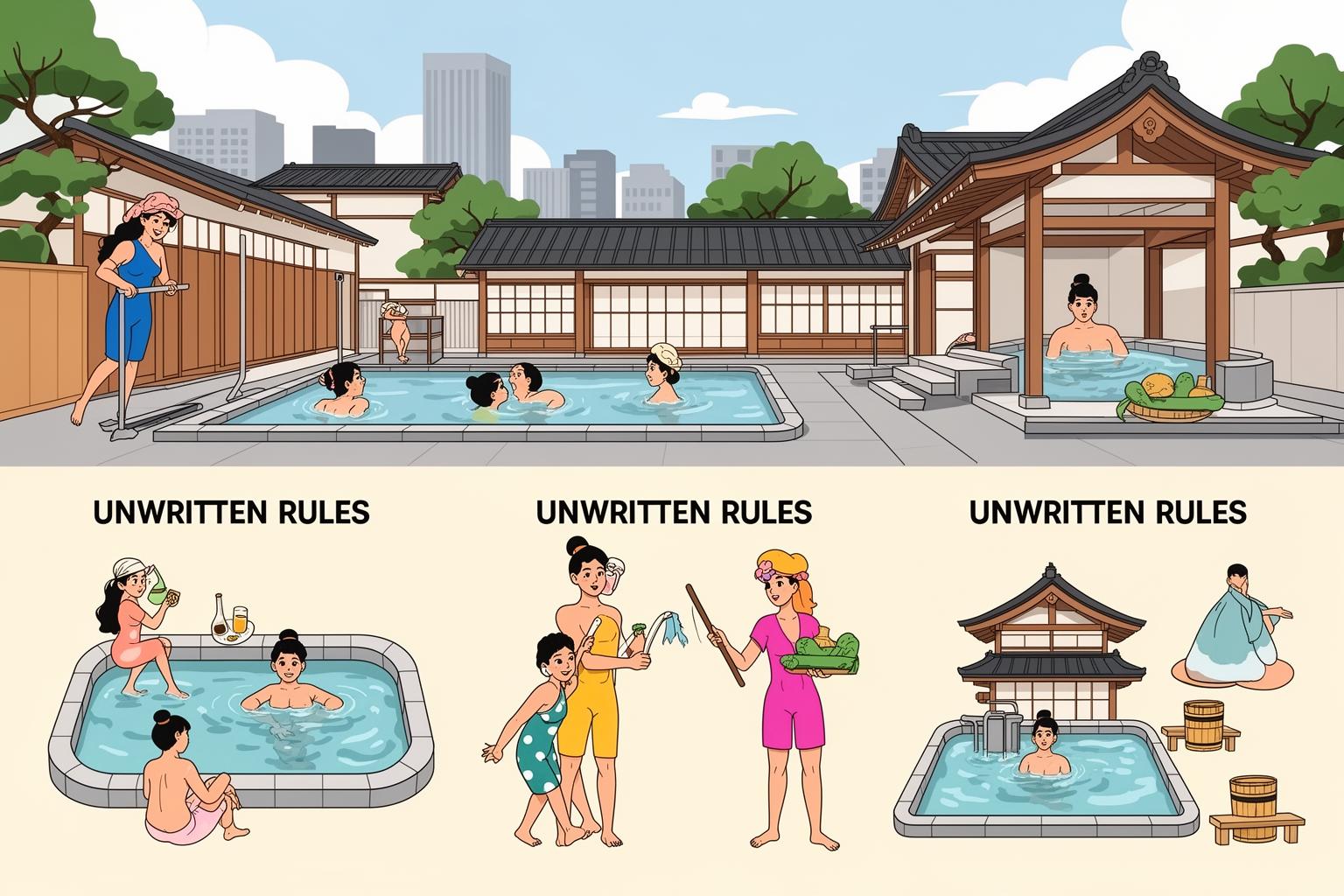

The Unwritten Rules: A Step-by-Step Guide to Sentō Etiquette

For a first-timer, the idea of navigating a sentō can seem somewhat intimidating. The rules are unspoken, and the customs deeply ingrained. But don’t worry; the process is logical, respectful, and once you understand it, becomes a reassuring routine. Think of it as a gentle dance, with steps you’re about to learn.

Your journey starts at the entrance. You’ll slide open the door and step into the genkan, a small entryway where you must take off your shoes. Locate an empty shoe locker, the getabako, place your shoes inside, and take the wooden key. This key is your initial pass into this world. Next, approach the reception desk, which might be a modern counter or a traditional raised platform known as a bandai. Here, you pay the bathing fee, usually a modest few hundred yen. If you haven’t brought your own supplies, this is the place to buy a small towel, soap, and shampoo. You’ll be directed to the appropriate changing room—typically indicated by a blue curtain with the character for man (男) or a red one with the character for woman (女).

Inside the datsuijo, or changing room, find an empty locker or a wicker basket. This is where you’ll store your clothes and belongings. Now comes the moment of truth: you must completely undress. There’s no need to feel shy; everyone is in the same situation, and nudity here is entirely non-sexual and matter-of-fact. You will require two towels: a large one for drying off at the end, which remains in your locker, and a small one, often called a “modesty towel,” that you take with you into the bathing area.

Before entering those inviting tubs, you must follow the cardinal rule of the sentō: wash yourself thoroughly. This is non-negotiable. Enter the main bathing hall and find an open washing station. Each station is equipped with a low stool, a bucket or washbowl, and a faucet with a shower hose. Sit on the stool—it’s considered rude to shower standing up, as you might splash others—and scrub your entire body with soap and shampoo. Use the shower to rinse off all the suds. You must be completely clean before entering the communal water. This ritual is the heart of the experience, a gesture of respect for the shared space and your fellow bathers.

Now, you’re ready to soak. This is the reward. As you approach the tubs, be mindful of your small towel. It must never touch the bath water. You can place it on the side of the tub or, as regulars do, fold it neatly on top of your head. Ease yourself into the water slowly—no jumping or splashing. The first tub, usually quite hot, is the atsuyu. Let your body adjust, feel the heat seep into your muscles, and allow yourself a gentle, contented sigh. This is perfectly normal and part of the experience. Explore the various baths. There might be a cooler one (nuruyu), a bath with powerful jets for massaging your back (jetto basu), or even a denki-buro, an electric bath. A word of caution about the denki-buro: it sends a low-voltage current through the water creating a tingling, buzzing sensation in your muscles. It’s an acquired taste and can be surprising if you’re not prepared! Approach it carefully and don’t stay too long. Some sentō also offer herbal baths (yakuyu) with seasonal infusions, or an outdoor section called a rotenburo, where you can soak under the open sky.

Regarding tattoos, the situation can be complicated. Historically linked to the yakuza, tattoos are often banned in more formal hot spring resorts, or onsen. However, neighborhood sentō in cities like Osaka are often much more lenient. Many have no restrictions at all, while some might ask that you cover small tattoos with a patch. It’s always wise to check the sentō’s policy online if possible, or simply heed the signs at the entrance. If uncertain, discretion is advised. The relaxed, local atmosphere of a sentō generally makes it a more welcoming environment for tattooed visitors than a high-end onsen.

Once you’ve soaked to your heart’s content, the final steps are equally important. Before returning to the changing room, use your small towel to wipe off as much excess water from your body as possible. The aim is to avoid dripping all over the datsuijo floor, another simple act of communal respect. Back at your locker, you can finally use your large, dry towel. This moment is pure bliss—feeling completely clean, warm, and relaxed.

Beyond the Bath: The Art of Post-Sentō Relaxation

The sentō experience doesn’t conclude the moment you step out of the water. The post-bath ritual is a vital part of the culture, serving as a gentle transition back into the world. In the changing room, there’s no hurry. People take their time, using the hair dryers provided or standing before a large, powerful fan. You might notice regulars weighing themselves on an old-fashioned analogue scale or enjoying an energetic session on a noisy massage chair.

Arguably, the most cherished element of this ritual is the post-bath drink. Almost every sentō features a vending machine or fridge stocked with small glass bottles of milk—plain, coffee-flavored, and various fruit flavors. There is something indescribably perfect about drinking a cold, sweet beverage after being warmed to your core. For many Japanese, it’s a tradition that evokes childhood memories—a simple, nostalgic delight. For adults, a cold beer is an equally favored option. The classic image is one hand resting on the hip, the other lifting the bottle, accompanied by a look of complete satisfaction.

Many sentō also include a small relaxation lounge, the kyukeishitsu, adjacent to the changing area. This space might have tatami mats, a few tables, and a television that’s always tuned to a baseball game or variety show. Here, you’ll find people lounging, reading manga or newspapers, and continuing the conversations sparked in the bath. This is the closing chapter of the sentō as a community hub—a place to linger and allow the feeling of yu-agari—that post-bath glow—to fully settle. Walking home afterward, your skin tingling and your body feeling light as a feather, especially on a cool Osaka night, is a simple yet profound pleasure. You leave feeling refreshed, not only physically but socially and spiritually as well.

Finding Your Neighborhood Gem: A Few Osaka Sentō Styles

Although they share a common purpose, not all sentō are alike. Osaka offers a rich diversity, each with its own distinct character. You can discover the perfect bath to suit your mood.

First, there is the Classic Showa-Era Sentō, the quintessential neighborhood institution. It might be hidden down a quiet residential street or located at the end of a covered shotengai shopping arcade. Its exterior will be modest, while the interior feels like a time capsule. Picture vintage tile work, the iconic Mount Fuji mural, and a loyal clientele of elderly locals who have frequented it for decades. The water will be steaming hot, the conversation lively, and the experience entirely authentic. This represents the sentō in its purest, most traditional form.

Next, there is the Super Sentō. These are larger, more contemporary establishments focused less on daily routine and more on providing a comprehensive relaxation experience. They often feature a broad selection of baths and saunas, including carbonated springs, saunas with “löyly” steam rituals, and extensive outdoor bathing areas. Examples like Naniwa no Yu, perched atop a building with city views, fit this category. They usually include restaurants, massage services, and spacious lounges, making them ideal for a half-day or full-day retreat. They also serve as an excellent, less intimidating introduction for beginners.

Lastly, there’s the emerging category of the Designer Sentō. These are often older bathhouses rescued from closure and lovingly refurbished by a younger generation of owners. They achieve a brilliant balance between preserving the nostalgic charm of the original structure and adding a touch of modern style. The decor might be minimalist and stylish, the music cool jazz instead of television, and you might find a craft beer bar or a small café in the lobby. These venues attract a new, diverse crowd and revitalize the ancient culture of public bathing, demonstrating that the sentō is not merely a relic of the past but a vibrant part of Osaka’s future.

Practical Pointers for Your First Plunge

Ready to take the plunge? A few final tips will help make your first sentō visit smooth and enjoyable. While some regular bathers bring their own personalized soaps and shampoos, you don’t actually need to bring anything. Nearly every sentō offers a tebura setto, or “empty-handed set,” for a small additional fee. This usually includes rentals of a small and large towel, plus single-use packets of body soap, shampoo, and conditioner. It’s very convenient.

The price for a basic sentō in Osaka is standardized and quite affordable, typically around 500 yen for adults. Super sentō tend to be pricier, generally ranging from 800 to over 2,000 yen depending on the amenities and day of the week. Most sentō open in the mid-afternoon, around 2 or 3 PM, and remain open late, often until midnight or 1 AM. Visiting on a weekday afternoon is a great way to enjoy a quieter, more spacious atmosphere, often shared with retirees. The evenings, from after work until closing, are usually the busiest, with a lively, social vibe.

Don’t worry if your Japanese is limited. The experience is very visual, and staff are accustomed to newcomers. A smile and a simple arigatou gozaimasu (thank you very much) will be warmly appreciated. The key is to observe what the locals do and follow their example. The etiquette centers on mutual respect and keeping a clean, peaceful environment for everyone. Relax, go with the flow, and enjoy the experience without overthinking it.

A Warm Embrace in the Heart of the City

In a world that often feels increasingly fragmented, the Osaka sentō remains a powerful and beautiful anachronism. It is a place where the simple, ancient act of bathing transforms into a meaningful ritual of community and connection. This space breaks down social barriers, inviting you to shed not only your clothes but also the stresses and pretensions of everyday life. To enter a sentō is to step into the warmth of a shared history, to sense the heartbeat of a neighborhood, and to engage in a daily practice that has comforted and cleansed the people of this city for generations. It is more than just a bath; it is an immersion into the very essence of Osaka. So, bring a small towel, leave your inhibitions behind, and experience the unique pleasure of this local tradition. It offers a chance to wash away the weariness of your travels and soak in the genuine, unfiltered warmth of Osaka, one neighborhood bath at a time.