Step off the train at Juso Station, and you’re immediately plunged into a different Osaka. This isn’t the polished, futuristic gleam of Umeda or the dazzling, tourist-thronged canals of Dotonbori. This is something else entirely. Juso is raw, a little rough around the edges, and pulsating with a vibrant, unapologetic local energy. The air hums with the rattle of the Hankyu trains overhead, the clatter of pachinko balls, and the low murmur of conversations spilling from countless tiny bars and eateries. It’s a district that lives and breathes for the night, a labyrinth of narrow streets and glowing neon that holds one of Osaka’s most cherished culinary treasures: authentic, no-frills, unbelievably delicious Kushi-katsu. For the traveler seeking to peel back the layers of this city and taste its true soul, the journey begins here. This isn’t just about finding a meal; it’s about finding a feeling, a memory of a Japan that exists just beyond the reach of the guidebooks, a place where food is not just sustenance, but the very fabric of community. In Juso, every crispy, golden-fried skewer tells a story of Osaka’s working-class spirit, its love for good, honest food, and its warm, welcoming heart. Forget what you think you know about Japanese cuisine and prepare to dive into the deep-fryer of local life. The real Osaka is waiting.

For a different perspective on Osaka’s retro charm, explore the nostalgic streets of Nakazakicho.

The Soul of Osaka on a Stick: Deconstructing Kushi-katsu

Before you can truly savor the quest for the perfect skewer in Juso, you first need to understand the art of Kushi-katsu. At its core, Kushi-katsu means “fried skewers.” However, this straightforward description masks a rich culinary tradition deeply embedded in Osaka’s identity. It’s more than just fast food; it’s a world of flavor and texture, exemplifying the Japanese philosophy of refining a simple idea to near perfection. The practice is believed to have begun in Osaka’s Shinsekai district in the late 1920s, created by a restaurateur aiming to provide a quick, affordable, and satisfying meal for local laborers. Skewering pieces of meat and vegetables, breading, and deep-frying them was an efficient way to serve hearty food that could be eaten standing up. What started as a humble worker’s meal evolved into a cherished culinary institution celebrated nationwide, though its true heart remains in Osaka’s bustling streets.

The Anatomy of a Perfect Skewer

What elevates a simple skewer into a Kushi-katsu masterpiece? It’s a harmony of four essential elements, each playing a vital role. First, the ingredients. The charm of Kushi-katsu lies in its versatility. Almost anything can be skewered and fried. Classics include juicy pork loin cubes (butabara), tender chicken thigh (momo), and lean beef (gyu-katsu). But the variety goes far beyond meat. Seafood shines with choices like succulent shrimp (ebi), plump scallops (hotate), and delicate white fish (kisu). Vegetables add contrast in texture and flavor. Thick onion slices (tamanegi) become sweet and tender when fried, while lotus root (renkon) keeps a pleasing, lace-like crunch. Shiitake mushrooms contribute earthiness, asparagus offers a fresh green note, and quail eggs (uzura no tamago) provide a creamy, comforting bite. Even cheese, mochi rice cakes, and small sausages feature on menus, demonstrating the cuisine’s playful, adaptable character.

Second is the batter and breading, the golden shell encasing each piece. This isn’t a heavy, dense batter like that on a corn dog. A proper Kushi-katsu batter is light and thin, designed simply to help the breadcrumbs stick. The real highlight is the panko, Japanese-style breadcrumbs. Unlike Western varieties made from toasted bread, panko uses bread baked without crusts and ground into large, airy flakes. When fried, these flakes absorb less oil, creating a coating that is incredibly light, crunchily shattering, and never greasy. Many chefs take pride in the fineness of their panko; some restaurants use a secret mix of flake sizes to achieve the ideal texture—a delicate crunch that yields to the tender ingredient inside.

Third is the oil, the medium where the magic unfolds. The type of oil, its temperature, and cleanliness are crucial. Many traditional shops use a blend of oils, often combining lard for richness with vegetable oil for a high smoke point. The oil must be kept meticulously clean, filtered daily to remove crumbs that could burn and produce bitterness. The temperature is managed with almost obsessive precision. Too low, and the skewers soak up excess oil, becoming greasy. Too high, and the panko burns before the ingredient cooks through. The perfect temperature rapidly seals the skewer, cooking the ingredient with steam from its moisture while crisping the panko to a flawless golden hue. A skilled chef constantly adjusts the heat, adding new skewers on one side of the fryer while moving others, interpreting the oil bubbles like a language.

Finally, there is the sauce, the lifeblood of the Kushi-katsu experience. It is a communal dipping sauce—typically a thin, dark, savory-sweet blend based on Worcestershire sauce, soy sauce, and other secret ingredients. Tangy, slightly fruity, and deeply umami, it cuts through the richness of the fried food without overwhelming it. The sauce sits in a stainless-steel tray on the counter, shared by all diners. This communal setup gives rise to the most important rule in Kushi-katsu culture, posted in every shop: “Nido-zuke Kinshi” (二度漬け禁止), meaning “No double-dipping.” Once you take a bite, your skewer must never go back into the shared sauce. This rule is one of hygiene and respect; violating it is the ultimate faux pas. It’s a simple code that unites everyone within the intimate space of a Kushi-katsu eatery.

Juso: A Portrait of an Unfiltered Entertainment District

To grasp why Juso is the ideal destination for this culinary journey, you first need to fully immerse yourself in its atmosphere. Above all, Juso is a transportation hub. Three distinct Hankyu railway lines—to Kobe, Kyoto, and Takarazuka—meet at its station, making it a vital junction for commuters throughout the Kansai region. This constant stream of people fuels the district’s relentless energy, creating a sense of perpetual motion. When you leave the station, you won’t find grand department stores or tourist information booths; instead, you encounter a dense, chaotic, yet oddly harmonious urban environment.

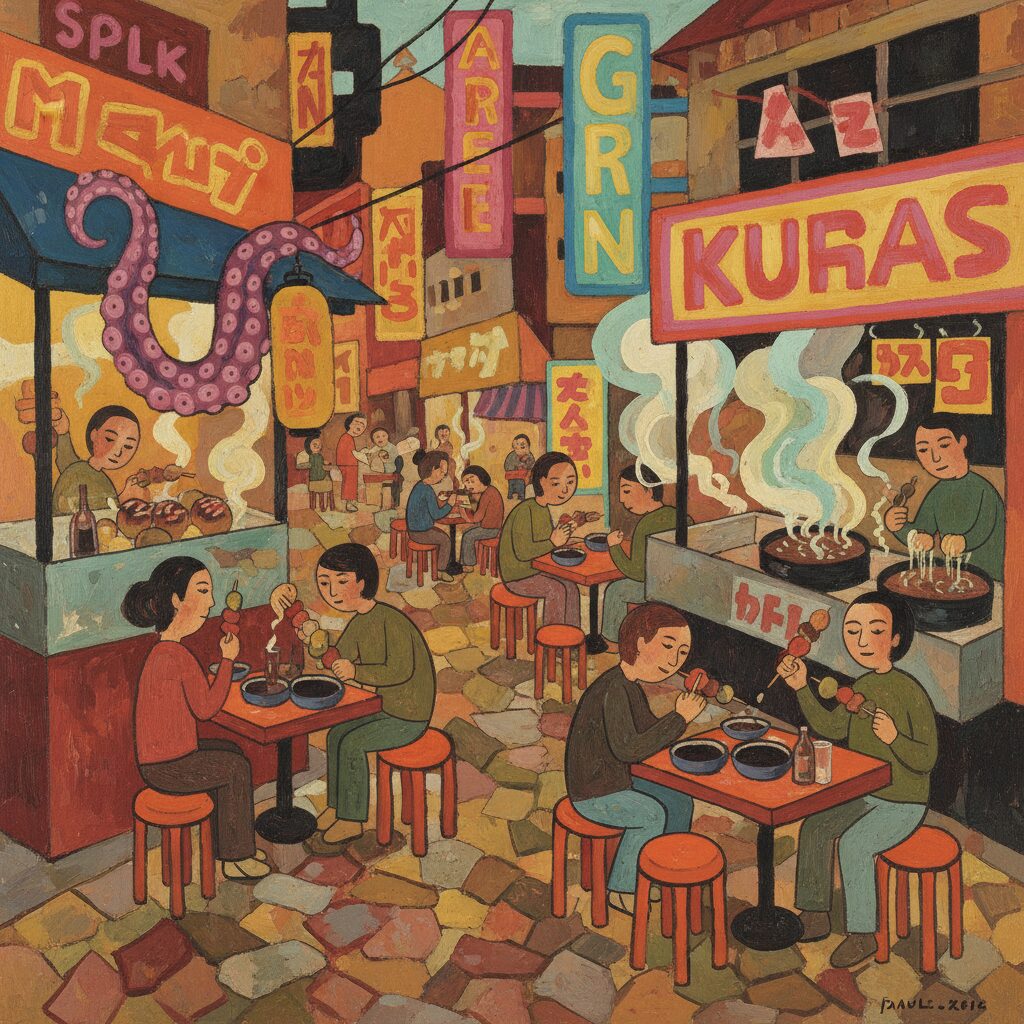

The area is split by elevated train tracks into east and west sides, each with its own unique character. The west side, often referred to as “Shonben Yokocho” or “Piss Alley” (a gritty yet affectionate nickname common in many old Japanese entertainment districts), is a maze of impossibly narrow alleys. Tiny tachinomi (standing bars) and kushi-katsu joints are packed shoulder-to-shoulder here, their red lanterns casting a warm glow on the street. The air is thick with the aromas of grilled meat, simmering dashi, and frying oil. It’s a spot where salarymen, still in their suits, relax with a cold beer and a few skewers before catching their last train home. The architecture is a hodgepodge of post-war buildings, many untouched for decades. The place feels genuine, lived-in, and completely free of pretense.

The east side is somewhat more spacious but equally vibrant. Here lies the Juso Fureai Shotengai, a covered shopping arcade at the district’s commercial core. Unlike the tourist-focused arcades in Namba, this one caters to locals. You’ll find small greengrocers, fishmongers, traditional Japanese sweet shops, and pharmacies. Intermixed among these are the staples of Juso’s entertainment scene: pachinko parlors with their noisy soundtracks and flashing lights, and a notable number of “love hotels,” discreet in entrance but revealing flamboyant facades. This blend of the everyday and the risqué is quintessential Juso. It doesn’t hide its identity; instead, it displays it proudly. This is an adult district, a space for release and leisure, where local eateries and bars fuel the nightlife nonstop.

Juso as a whole evokes a feeling of stepping back into the Showa Era (1926-1989). The neon signs possess a slightly faded, analog charm. Storefronts are typically small, family-run businesses. There’s a palpable sense of community and a daily rhythm that feels authentic and unpolished. You observe elderly residents doing their shopping, students grabbing affordable meals after school, and couples heading to old-fashioned movie theaters still thriving here, such as the Juso Nanagei, known for its eclectic mix of independent and classic films. Juso doesn’t cater to tourists; it simply exists as it is and invites you to experience it on its own terms. This genuine authenticity makes it an ideal place to discover true kushi-katsu. The restaurants rely not on gimmicks but on the quality of their food and the loyalty of their local patrons. To succeed in this tough, straightforward environment, they must be both excellent and affordable.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Finding Your Perfect Kushi-katsu Joint

Your adventure begins the moment you enter the maze of streets around Juso Station. There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of spots serving Kushi-katsu, ranging from dedicated specialty shops to general izakayas that feature it on their menus. The sheer abundance of choices can be overwhelming, but the search is part of the fun. This is not a time for online reviews or top-ten lists; it’s a moment for intuition and keen observation.

Your first encounter will likely be at a tachinomi Kushi-katsu-ya. These standing-only bars usually have just a simple counter separating customers from the chef and the deep-fryer. They are the epitome of cheap and cheerful. The atmosphere is loud, lively, and incredibly fast-paced. You squeeze into a spot at the counter, shout your order for a beer and a few skewers, eat quickly, and move on. These places are the domain of local workers—you’ll see men in construction uniforms, office workers with loosened ties, and shopkeepers from the nearby arcade. The Kushi-katsu here is straightforward and delicious, with skewers often priced as low as 100 or 120 yen each. The experience is exhilarating and deeply local, but the speed and lack of English can be intimidating for first-timers.

If you prefer a more relaxed pace, seek out the small, family-run establishments. These are often recognizable by their noren—traditional fabric dividers hanging at the entrance—and their warm, inviting glow. Peering inside, you’ll typically find a single wooden counter seating about eight to ten people. Behind it, an older couple or a single master chef works, with the husband frying skewers while his wife takes orders and serves drinks. This is where the true magic happens. The experience is intimate and personal. You are not just a customer; you are a guest in their home. The menu might be entirely in Japanese, handwritten on strips of paper pasted to the wall. It’s the perfect opportunity to use the traveler’s best phrase: “Omakase onegaishimasu,” meaning “Chef’s choice, please.” Entrusting your meal to the chef shows respect and trust, and you’ll be rewarded with a perfectly paced selection of the freshest, finest ingredients of the day.

Lastly, there are the larger izakaya-style restaurants specializing in Kushi-katsu. These offer table seating as well as a counter, making them a comfortable choice for groups or those who prefer not to stand. They typically have broader menus, featuring a wider variety of skewers, side dishes like doteyaki (slow-cooked beef sinew) and salads, and an extensive drink selection. Though they might feel slightly less traditional than the tiny counter-only spots, they remain authentically Osakan and provide an excellent, accessible introduction to Kushi-katsu. The quality can be just as high, and the more spacious setting allows for a more leisurely dining experience.

When picking your spot, rely on your senses. Look for places crowded with locals; a full house is always a good sign. Listen for the sizzle of the fryer and the cheerful chatter of patrons. Smell the air for the fresh, inviting aroma of hot oil and savory sauce—not the stale odor of old grease. Observe the chef: do they move with confident, practiced efficiency? Does the space appear clean and well-maintained? Trusting these instincts will almost always guide you to a memorable meal and a place that feels just right.

The Ritual of Eating: A Step-by-Step Guide to the Juso Kushi-katsu Experience

Once you’ve selected your sanctuary, the true ritual commences. This is a performance where you are both observer and participant—a culinary ceremony with its own distinct etiquette and rhythm.

Entering and Ordering

Push aside the noren curtain and step inside. You’ll be greeted with a warm “Irasshaimase!” (“Welcome!”). Find an available spot at the counter. The chef will likely ask for your drink order first. The classic, unbeatable pairing for Kushi-katsu is a cold, draft beer (“nama biru”). As your beer is poured, you’ll receive a small wet towel (oshibori) to clean your hands. In front of you will be the holy trinity of the Kushi-katsu experience: the communal dipping sauce pot, a small dish for your used skewers, and a bowl of fresh, crisp cabbage leaves. The cabbage serves a dual purpose: it refreshes your palate, cutting through the richness of the fried food with its crunch, and it acts as a tool, which we’ll explain shortly.

Now, it’s time to order your skewers. If there’s a menu you can read, feel free to point. If not, this is the moment to go “omakase.” Alternatively, you can start with the basics. “Buta” (pork), “ebi” (shrimp), “renkon” (lotus root), and “tamanegi” (onion) make excellent first picks. Usually, you order a few at once. The chef will nod in acknowledgment, then turn to his ingredients, skillfully battering and breading your selections before gently lowering them into the hot oil.

The Golden Rule in Action

Within minutes, the skewers will arrive, served on a metal tray before you. They’ll be radiant, golden, and piping hot. The chef will gesture toward the sauce container. This is the moment of truth. Take your first skewer, hold it by the end, and dip it deeply into the dark, savory sauce. Swirl it around to coat evenly. Lift it out, let any excess drip off, and bring it to your mouth. This is your one and only opportunity to dunk that skewer into the communal sauce. The rule of “Nido-zuke Kinshi” is strict: once your mouth has touched that skewer, it must not re-enter the pot.

But what if you want more sauce halfway through a large piece of onion or pork? This is where the cabbage comes into play. The cabbage leaves serve as your personal, edible ladles. You can dip a clean piece of cabbage into the sauce, then use it to drizzle more sauce onto your skewer. It’s a clever system that preserves hygiene while ensuring your flavors never fall short. Watching the locals do this with effortless grace is part of the learning experience.

Savoring the Flavors: A Journey Through the Menu

Now, the feast truly begins. Each skewer is a tiny universe of flavor and texture.

The Butabara (pork belly) is essential. The fat melts down, rendering the meat tender, while the panko forms a crispy shell—it’s the perfect blend of savory and rich.

The Gyu-katsu (beef) is hearty and satisfying, its robust flavor pairing perfectly with the tangy sauce.

The Ebi (shrimp) is a classic. The shrimp’s natural sweetness contrasts beautifully with the savory crust, feeling like a celebration on a stick.

The Kisu (sillago fish) offers a more delicate experience. The flaky white fish is light and clean-tasting, a lovely counterpoint to the richer meat options.

The Tamanegi (onion) is a revelation. Thick-cut rounds become meltingly soft and incredibly sweet when fried—a testament to how deep-frying transforms a humble vegetable.

The Renkon (lotus root) emphasizes texture. It stays delightfully crunchy and fibrous, its earthy flavor a joy. The lace-like holes also make it visually striking.

The Nasu (eggplant) soaks up the oil like a sponge, becoming creamy and decadent with a deep, savory taste.

The Shiitake mushroom is an umami powerhouse, its earthy, meaty texture a wonderful surprise.

The Uzura no Tamago (quail egg) delights with a crisp exterior giving way to a perfectly cooked, creamy yolk.

The Asparagus skewer, often a whole spear, brings a fresh, green, slightly bitter note that cuts through the richness beautifully.

Don’t hesitate to be adventurous. Try the cheese, which melts into a gooey, stringy treat inside its crispy shell. Or the mochi, which turns wonderfully soft and chewy. Some shops offer more exotic items like kujira (whale) or seasonal delights such as kaki (oyster) in winter or ginnan (ginkgo nuts) in autumn. As you enjoy, place your used bamboo skewers into the provided container. This is how the staff will tally your bill at the end—a simple, honest, analog system.

Beyond the Skewer: Exploring Juso’s Other Charms

While Kushi-katsu may be the main attraction, Juso has much more to offer the curious traveler willing to stay a while. A short walk from the station leads you to the banks of the Yodogawa River. This wide, open river provides a refreshing escape and a beautiful natural contrast to the dense urban surroundings of the district. The riverbanks are popular spots for jogging, cycling, and relaxing, with stunning views of the Umeda skyline in the distance. In early August, this area hosts the Naniwa Yodogawa Fireworks Festival, one of Japan’s largest and most spectacular fireworks events, attracting huge crowds to the riverbanks.

Juso is also an excellent place to explore other aspects of Osaka’s “konamon” or “flour-based food” culture. The district is especially known for Negiyaki, a savory pancake related to the more famous Okonomiyaki. Unlike Okonomiyaki, which is heavy on cabbage, Negiyaki is filled with plenty of green onions (negi), giving it a sharper, fresher taste. It’s usually thinner and served with soy sauce instead of the sweet Okonomiyaki sauce. Visiting a small Negiyaki shop, like the renowned “Yamamoto,” and watching it prepared on a large teppan grill is a quintessential Juso experience.

For a dose of culture, the well-known Juso Nanagei theater is a local landmark. It’s a throwback to an era before multiplex cinemas, a place that celebrates film as an art form. Watching a movie here, even without understanding the language, means taking part in a piece of living local history. The shopping arcades are also worth a leisurely stroll. They offer a glimpse of daily life that’s becoming increasingly rare in Japan’s major cities. You can find tiny shops selling handmade senbei rice crackers, local sake, or traditional kitchenware, all while soaking in the relaxed pace of the neighborhood.

Practicalities for the Intrepid Traveler

Navigating Juso is surprisingly straightforward, but a few tips can help ensure your visit goes smoothly.

Access

Juso Station is not served by JR or subway lines. Instead, it is a key hub solely for the private Hankyu Railway. This makes it very convenient to reach from Osaka-Umeda Station (the main Hankyu terminal). The express train takes only three minutes, making it one of the most accessible yet distinct neighborhoods away from the city center. This brief travel time means you can easily enjoy an evening meal and return to your hotel quickly.

Best Time to Visit

Juso truly comes alive as the sun sets. Although the shopping arcades operate during the day, the real charm emerges from late afternoon onward. Plan to arrive around 5 or 6 PM to witness the neighborhood’s transformation from its daytime atmosphere to a lively nightlife scene. Lanterns begin to glow, salarymen start filling the bars, and the sound of Kushi-katsu fryers sizzling seems to intensify. By this time, most of the top eateries are in full operation.

Language and Etiquette

Don’t be discouraged by the limited English. Juso is a local-focused area, and English menus are uncommon. However, the language of food is universal. A smile, a simple gesture, and a polite “arigato gozaimasu” (thank you very much) will take you far. Locals are typically friendly and appreciate visitors who venture off the usual tourist path. Keep in mind the important rule of no double-dipping. Also, in small izakayas, it’s customary to order at least one drink per person. When ready to leave, say “Okanjo onegaishimasu” (“The bill, please”), and the staff will total your skewers.

Money

Cash reigns supreme in Juso. While some larger establishments may accept credit cards, most of the small, cozy spots that provide the best experience operate on a cash-only basis. Make sure to bring enough yen before indulging in the neighborhood’s culinary treats. The good news is that a truly satisfying Kushi-katsu meal with a couple of beers is very affordable, often costing just a fraction of what a similar meal would in a more tourist-heavy area.

A Taste of the Real Osaka

Leaving Juso, with the lingering taste of savory sauce and crispy panko on your palate, you feel as if you’ve been let in on a secret. This isn’t an experience crafted for tourists; it’s one you have to seek out and actively participate in. A visit to Juso is more than a culinary adventure; it’s a cultural immersion. It’s an opportunity to connect with the raw, working-class spirit of Osaka, a city proud of its delicious food culture (known as “kuidaore,” meaning to eat until you drop) and its warm, down-to-earth people.

In the neon-lit alleys of this lively district, you realize that the heart of a city isn’t always found in grand monuments or famous landmarks. Sometimes, it’s discovered at a crowded counter, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers, sharing a pot of sauce, and delighting in the simple, profound joy of a perfectly fried skewer. It serves as a reminder that the most memorable travel experiences are often the most genuine, authentic, and deliciously human. Juso offers just that, one golden, crispy, unforgettable bite at a time.