Step off the humming tram in southern Osaka, and the air changes. The urban clamor softens, replaced by a stillness that feels ancient, carrying the faint, briny scent of a sea that once lapped much closer to these sacred grounds. This is the entrance to Sumiyoshi Taisha, a place that is not merely a destination but a passage through time. Before you stands a breathtaking vermilion bridge, its arch so steep it seems to touch the heavens, mirrored perfectly in the tranquil pond below. This is the Sorihashi, the iconic drum bridge, and to cross it is to leave the modern world behind and step into a narrative that predates Buddhism in Japan, a story woven from sea spray, imperial ambition, and the very essence of Shinto belief. Sumiyoshi Taisha is more than one of Japan’s oldest and most important shrines; it is a living monument to the nation’s profound and enduring connection to the ocean, a sanctuary where the gods of the sea have been worshipped for nearly two millennia. It is here, among primeval camphor trees and halls built in a starkly beautiful, purely Japanese style, that you can feel the rhythmic pulse of a history that shaped not just Osaka, but the entire archipelago. This is a journey to the spiritual bedrock of Japan, a place where every stone lantern and wooden beam tells a tale of epic voyages and heartfelt prayers for safe return.

この古代の聖域を訪れた後は、大阪の豊かな文化のもう一つの層である伝統的な文楽人形劇の世界を探索してみるのも良いでしょう。

A Voyage Back in Time: The Genesis of a Maritime Sanctuary

The story of Sumiyoshi Taisha begins not with stone and wood, but with legend and water. Its origins trace back to the 3rd century, a time shrouded in the mists of mythohistory, entwined with the formidable figure of Empress Jingū. According to ancient chronicles, the Empress was preparing for a military expedition to the Korean peninsula when she received a divine oracle. Three powerful kami, the gods of the sea, appeared to her, promising protection and victory for her fleet in exchange for their proper enshrinement upon her return. These deities were the Sumiyoshi Ōkami: Sokotsutsu no O no Mikoto, the god of the seabed; Nakatsutsu no O no Mikoto, the god of the middle waters; and Uwatsutsu no O no Mikoto, the god of the sea’s surface. True to their word, the Empress’s campaign was victorious. Upon her triumphant return, guided by another divine sign, she established this very shrine to honor their pact. The fourth main sanctuary was later dedicated to the Empress herself, Okinagatarashihime no Mikoto, elevating her to the status of a guardian deity alongside the powerful sea gods she revered. This founding narrative anchors Sumiyoshi Taisha’s identity, forever linking it to divine protection, safe passage, and the immense power of the ocean.

The shrine’s strategic location was no coincidence. In ancient times, the coastline of Osaka Bay extended further inland, bringing the sea almost to the shrine’s doorstep. It sat at the mouth of the Hosoe-gawa, a river flowing into the bay, making it a natural harbor and vital departure point. For centuries, Sumiyoshi Taisha served as the spiritual gateway to the world beyond Japan’s shores. It was from here that the imperial court dispatched its most important missions, the Kentōshi, official embassies to Tang Dynasty China. Picture the scene: fleets of wooden ships, laden with scholars, monks, diplomats, and precious goods, gathering in the bay. Before venturing into the treacherous waters of the East China Sea, the entire delegation would visit Sumiyoshi Taisha to perform elaborate rituals, praying to the Sumiyoshi Ōkami for favorable winds and a safe return. The shrine became a nexus of international exchange and cultural transmission, a place where the fate of diplomacy and the lives of sailors were entrusted to the sea gods. This imperial patronage secured its status as a first-rank shrine, a protector of the state itself. Its influence permeated Japanese culture, with the Sumiyoshi deities also revered as gods of waka poetry, their raw, elemental power inspiring creative spirit. Throughout history, from Heian-period aristocrats to the powerful samurai warlords of the medieval era and the wealthy merchants of Edo-period Osaka, people whose lives and fortunes were tied to the sea have made pilgrimages to these grounds, their prayers echoing through the centuries.

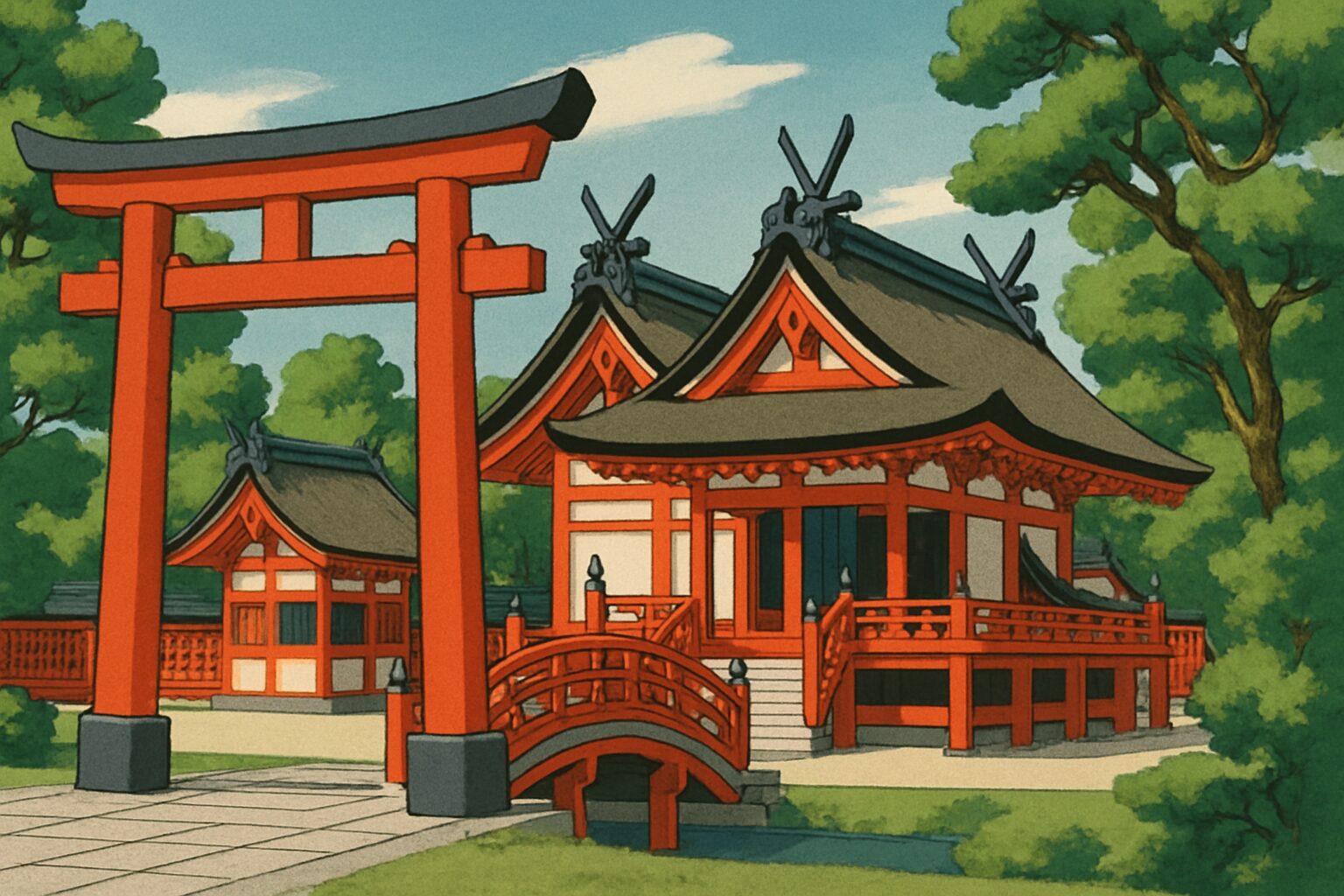

Echoes of the Divine: The Sumiyoshi-zukuri Architectural Style

Strolling through the grounds of Sumiyoshi Taisha is like witnessing an architectural language spoken in a dialect that has nearly disappeared from the rest of Japan. The four main sanctuaries, or Honden, are designated National Treasures, not only because of their age but for being the purest examples of a style known as Sumiyoshi-zukuri. This architectural form is entirely Japanese, conceived before the significant cultural influence from the Asian mainland introduced the sweeping, ornate roofs and intricate bracket systems of Buddhist temple architecture. What you encounter here is a powerful, primeval aesthetic—a direct dialogue between humanity, nature, and the divine.

The most distinctive aspect of Sumiyoshi-zukuri is its profound simplicity and linearity. The roofs are gabled and perfectly straight (kirizuma-zukuri), slicing through the sky with clean lines, completely lacking the elegant upward curves that later became a hallmark of Japanese design. This straightness is thought to represent the shape of ancient fishing boats turned upside down, a subtle tribute to the shrine’s maritime roots. Rising from the roof’s peak are two prominent decorative elements. The first are the chigi, forked finials that extend sharply outward and upward from the gable’s bargeboards. At Sumiyoshi, these are pointed sharply, projecting an impression of masculine strength and power. Lying horizontally across the roof’s ridge are the katsuogi, short cylindrical billets resembling logs. While now primarily decorative, these elements are believed to be remnants of ancient construction techniques, retained for their symbolic significance and sacred authority.

Another key feature is the entrance. Unlike most shrine styles where the entry is on the long, non-gabled side, in a Sumiyoshi-zukuri building the entrance is on the gabled end (tsumairi), meaning you approach directly toward the roof’s peak. This creates a more direct and commanding approach, focusing the worshipper’s attention. The main building is enclosed by a simple inner fence, and the entire structure is painted in vibrant contrasting colors: the walls coated with white gofun (a powder made from crushed seashells), while the pillars, roof beams, and fences are a brilliant vermilion. This striking combination, set against the dark, unpainted cypress wood of the roof, creates a visual rhythm that is at once earthy and ethereal. The four main halls are arranged uniquely in a straight line, one behind the other, like a fleet of ships sailing toward the sea. This layout exists nowhere else in Japan and serves as a powerful spatial expression of the shrine’s purpose. Standing before these structures, you are beholding a three-dimensional piece of history—a blueprint of a belief system that recognized divinity in the raw, unadorned forms of nature itself.

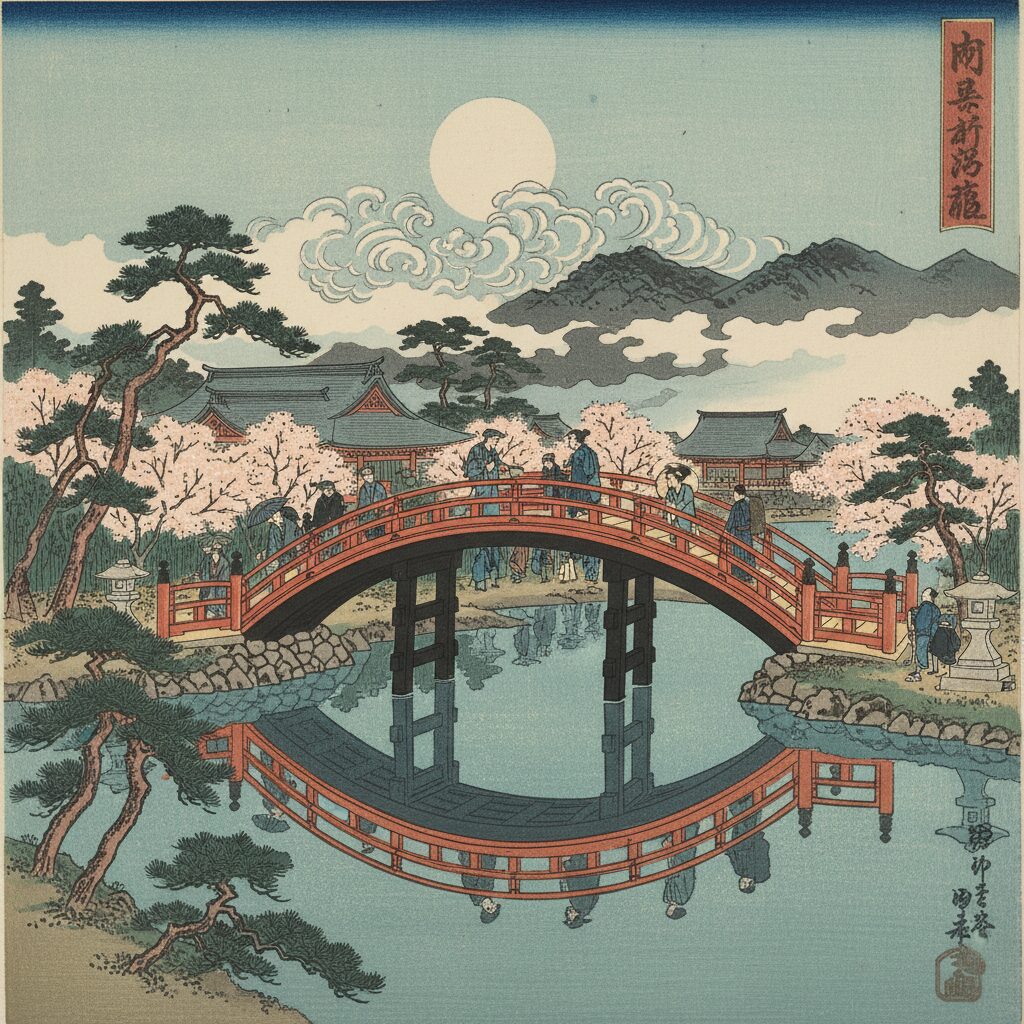

Crossing the Threshold: The Iconic Sorihashi Bridge

Before one can even approach the sacred sanctuaries, a rite of passage must be undertaken. This takes the form of the Sorihashi Bridge, often known as the Taiko-bashi or Drum Bridge, named for its deeply rounded shape. This structure is more than just infrastructure; it serves as the spiritual and aesthetic centerpiece of Sumiyoshi Taisha, an unforgettable emblem that prepares visitors for the sacred space beyond. Its vibrant vermilion lacquer shines brilliantly against the green foliage of the surrounding trees and the blue sky above, while its reflection in the calm waters of the pond below creates a perfect, mesmerizing circle. The bridge’s arch is exceptionally steep, reaching a gradient of about 48 degrees at its highest point—an entirely deliberate design.

Crossing the Sorihashi is a physical act of purification. The steep incline compels you to slow down, watch your step, and remain present in the moment. As you climb up, your view is the sky; as you descend, your gaze falls to your own feet and the weathered stone steps beneath you. This prompts a moment of introspection, separating you from the ordinary world you are leaving behind. Symbolically, the bridge represents a rainbow—a celestial path linking the earthly realm of humanity with the sacred realm of the kami. By crossing it, you are not merely walking over water but symbolically cleansing yourself of impurities and ascending to a higher spiritual plane. The experience is both demanding and profoundly rewarding. Standing at its apex, you are granted a breathtaking view of the shrine grounds spread out before you, with ancient halls waiting in the distance. The bridge is a favored spot for photography, and justifiably so, but its true power lies in the emotion it evokes. It is a moment of transition—a tangible boundary between the profane and the sacred. To visit Sumiyoshi Taisha without crossing this bridge is to miss the very essence of the pilgrimage. Whether illuminated by the soft light of early morning or glowing under festival lanterns at night, the Sorihashi Bridge remains an enduring symbol of passage, purification, and the beautiful journey into the heart of faith.

The Four Sanctuaries: A Unique Formation on the Sacred Grounds

After crossing the Sorihashi Bridge and passing through the main gate, you enter the central precinct, where the four main sanctuaries stand in solemn, silent majesty. Their arrangement is among the most unique and significant features of Sumiyoshi Taisha. Rather than being clustered together or placed around a central courtyard, the four Honden are aligned in a straight line, all facing west. This orientation is highly unusual for Shinto shrines, which typically face south or east in accordance with ancient cosmological principles. At Sumiyoshi, however, the direction is deliberate and meaningful: they face the sea. Positioned as eternal guardians, they forever watch over the waters they command, maintaining a constant vigil for the sailors, explorers, and travelers who have prayed at their altars for millennia. This formation both visually and spiritually reinforces the shrine’s identity as the premier sanctuary of the ocean gods.

The procession of worship follows this linear path. The first three halls honor the three sea gods who comprise the Sumiyoshi Ōkami. The first, Dai-ichi Hongū, enshrines Sokotsutsu no O no Mikoto, god of the depths. The second, Dai-ni Hongū, is dedicated to Nakatsutsu no O no Mikoto, god of the middle seas. The third, Dai-san Hongū, honors Uwatsutsu no O no Mikoto, god of the surface waters. Together, they embody the ocean’s full might—from its mysterious floor to its storm-tossed waves. Each hall exemplifies Sumiyoshi-zukuri, a powerful repetition of this ancient architectural style. As you proceed from one to the next, walking on the crisp white gravel that carpets the sacred grounds, a sense of rhythmic reverence builds. The air remains still, infused with the scent of aged cypress and the faint aroma of incense. The final sanctuary, Dai-yon Hongū, stands slightly apart from the first three and is dedicated to Empress Jingū. Her presence completes the pantheon, honoring the human figure through whom the will of the gods was manifested.

To stand in this space is to feel the weight of history. The current buildings date from 1810, yet they are exact replicas of their predecessors, meticulously rebuilt according to ancient plans every few decades in a ritual of renewal. This means the structures you see today faithfully represent a design that has occupied this site for over a thousand years. The experience is deeply atmospheric. A profound, quiet power radiates from these simple wooden structures. They are not grand or ornate like a European cathedral; their majesty arises from their purity, antiquity, and steadfast dedication to a singular, profound purpose.

Whispers and Wishes: Exploring the Wider Shrine Precincts

Beyond the four principal sanctuaries, the extensive grounds of Sumiyoshi Taisha are scattered with numerous other spiritually significant sites, each adding depth to the shrine’s rich tapestry of belief. A short walk from the main halls leads to a particularly sacred area called Goshogozen. This stone-enclosed space is believed to be the exact spot where the Sumiyoshi Ōkami first descended to earth to be enshrined. It is a powerful spiritual location, and visitors partake in a unique ritual here. They carefully search among the smooth, grey stones for three special pebbles: one inscribed with the character for ‘Go’ (五, five), another with ‘Dai’ (大, big), and a third with ‘Riki’ (力, power). Finding and keeping these three stones as an amulet is said to grant the bearer physical strength, wisdom, and financial fortune. This interactive tradition creates a direct connection between visitors and the shrine’s foundational myth.

Along the main paths and throughout the wooded areas stand over 600 stone lanterns, or ishidōrō. Each lantern is a testament to the faith of past worshippers. Many were donated centuries ago by shipping magnates, maritime merchants, and entire seafaring communities from all over Japan. These offerings express gratitude for safe voyages, successful trade, and protection from the dangers of the sea. As you walk among them, reading the weathered inscriptions, you move through a library of prayers. They stand as silent, moss-covered witnesses to the shrine’s enduring role as the ultimate guardian for those whose livelihoods depend on the water.

The shrine grounds also serve as a refuge for nature. Giant camphor trees (kusunoki) tower over the buildings, their gnarled branches stretching out like ancient arms. Several of these are regarded as goshinboku, or sacred trees, believed to be inhabited by kami. Some are said to be more than 1,000 years old, with immense trunks and sprawling canopies that inspire awe and a sense of timelessness. To stand beneath one of these giants is to feel a profound connection to the natural forces revered in Shintoism. In addition to these features, the precincts contain dozens of smaller sub-shrines, known as sessha and massha. Each is dedicated to a different deity, from gods of commerce and matchmaking to gods of poetry and the performing arts. Exploring these smaller, often quieter corners of the shrine offers a richer understanding of the multifaceted and layered nature of Shinto belief, where the divine is found in every aspect of life and nature.

The Rhythm of the Seasons: Festivals and Rituals

Sumiyoshi Taisha is not merely a static museum; it is a vibrant, living center of worship, where its spiritual energy is most strongly felt during its annual festivals. These occasions showcase spectacular displays of tradition, community, and faith, offering visitors an opportunity to witness the shrine’s ancient customs come alive. The grandest among them is the Sumiyoshi Matsuri, held from July 30th to August 1st. It is the final major summer festival in Osaka and a magnificent event. The festival culminates with a procession in which the spirit of the main deity is transferred to a lavishly decorated portable shrine, or mikoshi. This mikoshi is carried through the streets by numerous energetic participants dressed in traditional attire. The highlight is the Mikoshi Arai Shinji, a purification ritual where the mikoshi is carried across the Yamato River. This act reenacts the shrine’s connection to water in a powerful and dramatic cleansing ritual that draws large crowds.

Another must-see event is the Otaue Shinji, or rice-planting festival, held on June 14th. This ancient ceremony, designated as an Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property of Japan, is one of the most elaborate of its kind. The festival takes place in the shrine’s sacred rice paddy and begins with a solemn ritual to purify the field and seedlings. Following this, a spectacular performance unfolds. Women dressed in colorful traditional costumes plant rice seedlings in precise rows while singing ancient songs. On a stage at the field’s center, costumed dancers perform various traditional dances, including the energetic Sumiyoshi Odori, all to pray for a bountiful harvest. It is a mesmerizing and beautiful ritual that connects the shrine to another vital aspect of Japanese life: rice cultivation. The event is a vibrant tapestry of color, music, and movement—a living prayer for fertility and abundance.

As with all major shrines in Japan, Sumiyoshi Taisha also serves as a focal point for Hatsumōde, the first shrine visit of the New Year. During the first few days of January, the shrine’s normally peaceful atmosphere transforms into a lively, festive energy. Millions of people come to offer their first prayers of the year, purchase amulets (omamori) for good fortune, and draw their fortunes (omikuji) for the year ahead. Food stalls line the pathways, offering traditional festival snacks, and the air is filled with a tangible sense of hope and renewal. Experiencing Sumiyoshi Taisha during one of these festivals reveals its spirit in full expression—a timeless connection between ancient ritual and the contemporary lives of the Japanese people.

Practical Guidance for the Modern Voyager

Reaching this ancient sanctuary is surprisingly easy and provides an opportunity to experience a distinctive aspect of Osaka life. The most straightforward way is to take the Nankai Main Line from Namba Station, a key hub in downtown Osaka. A brief local train ride will bring you to Sumiyoshi Taisha Station, situated right next to the shrine’s main entrance. For a more picturesque and memorable journey, however, consider riding the Hankai Tramway, affectionately called the ‘Chin-Chin Densha’ after the sound of its bell. As one of Japan’s few remaining streetcar lines, riding its quaint single-car trams feels like a gentle step back in time. Disembark at the Sumiyoshi Torii-mae stop, which, true to its name, brings you right in front of one of the shrine’s massive stone torii gates.

To fully savor the serene and sacred atmosphere of Sumiyoshi Taisha, it’s best to visit early in the morning. Before tour groups and larger crowds arrive, you can stroll the gravel paths in near solitude, hear the priests’ morning chants, and watch the soft light filtering through ancient camphor trees. The grounds are expansive, so wear comfortable shoes suitable for walking on uneven surfaces and climbing the steep Sorihashi Bridge. Upon entering the shrine grounds, you’ll find a water pavilion called a temizuya, used for a simple purification ritual: take the ladle with your right hand and pour water over your left hand, switch hands and pour water over your right. Then, pour a little water into your cupped left hand, rinse your mouth (do not swallow or drink directly from the ladle), and discreetly spit the water onto the ground. Finally, hold the ladle upright to let any remaining water run down and cleanse the handle. When praying at one of the main halls, the customary practice is ‘two bows, two claps, one bow.’ Toss a coin into the offering box, bow deeply twice, clap your hands twice, silently offer your prayer, and finish with one final deep bow. While these rituals are not obligatory, following them is a meaningful way to show respect and engage more deeply with the cultural experience. Don’t forget to look for a protective charm, or omamori, for safe travels (kōtsū anzen), a perfect keepsake from the guardian shrine of travelers.

An Enduring Legacy: The Soul of Maritime Osaka

Sumiyoshi Taisha is more than a historical landmark; it serves as an anchor, tethering the expansive, futuristic city of Osaka to its ancient, sea-shaped heritage. In a city renowned for its vibrant neon lights, exceptional culinary delights, and lively commercial atmosphere, this shrine presents a powerful contrast—a sanctuary of profound calm, natural beauty, and steadfast spiritual tradition. Visiting Sumiyoshi Taisha means peeling back the layers of contemporary Japan to uncover a cultural foundation that is elemental and pure. Here, in the crisp lines of its architecture, the westward orientation of its sanctuaries, and the timeless rituals conducted on its grounds, the nation’s deep, age-old connection with the sea is revealed. It reminds us that before Japan turned inward to refine the aesthetics of the tea ceremony or the samurai code, it looked outward across the vast, unpredictable ocean with reverence, ambition, and hope. Crossing the Sorihashi Bridge, you sense that history beneath your feet, walking the same path as imperial envoys, medieval shoguns, and countless sailors who placed their trust in the kami enshrined here. Sumiyoshi Taisha is not just a site to observe; it is a place to experience—the whisper of the sea breeze through ancient trees, the solemn strength of architecture born from the Japanese spirit, and the enduring pulse of a faith that continues to guide and protect. It is a journey into the very heart of maritime Japan, an experience that remains with you long after you return to the bustling city streets.