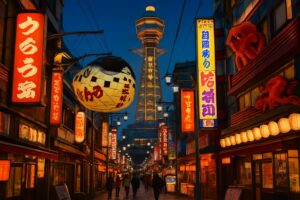

How do people manage to live in a city? It’s a question that echoes across the globe, from London to New York to Tokyo. You see the glittering skylines, the sleek trains, the endless options for food and entertainment, and the math just doesn’t seem to add up. You imagine a life of tiny, expensive apartments and a constant, draining anxiety about your bank balance. When you first look at Osaka, Japan’s third-largest city, you might feel that same familiar dread. It’s a sprawling metropolis, a concrete giant of commerce and culture. Surely, living here must mean a daily battle against exorbitant costs, right? This is where Osaka plays its first trick on you. The city, and its people, have a fundamentally different relationship with money than its eastern counterpart, Tokyo. And the secret, the living, breathing proof of this philosophy, isn’t hidden in a bank vault or an economic textbook. It’s laid bare for all to see, stretching 2.6 kilometers through the northern part of the city. It’s Tenjinbashisuji Shopping Street, the longest shotengai, or covered shopping arcade, in Japan. To a tourist, it’s a colorful novelty, a fun afternoon. To a resident, it is the entire operating system for a financially sustainable life. It’s the reason you can not only survive, but thrive, in Osaka on a budget that would be laughable in Tokyo. This street is more than a market; it’s a declaration of Osakan identity, a masterclass in pragmatic economics, and the pulsing, chaotic, unbelievably affordable heart of the city.

For a different perspective on how Osaka’s unique neighborhoods support a balanced lifestyle, consider exploring the quiet cafes perfect for remote work in Osaka’s Karahori district.

The Anatomy of a Bargain: Deconstructing the Shotengai Mentality

To truly understand Tenjinbashisuji, you first need to discard the modern, Westernized notion of shopping. It’s not about a calm, curated experience. It’s not about minimalist design, soft lighting, or convenience wrapped in packaging. The street is a vibrant, sensory overload, with every chaotic detail designed for one main objective: to showcase value. This is the essence of the Osaka shopper’s mindset. It’s not about just being cheap; it’s about being clever. It’s about getting the utmost utility from every single yen.

It’s More Than Cheap—It’s Value

The difference between cheapness and value is key. Anyone can offer a low price, but Osakan consumers are intensely focused on what they receive for that price. This is a city shaped by merchants, with a thousand-year legacy of trade embedded in every shopper. They are sharp, discerning, and have an almost uncanny sense of the market prices for everything from daikon radishes to toilet paper. A shopkeeper in Tenjinbashisuji can’t just cut prices to sell inferior goods—they’ll be exposed right away. Customers here can tell if fish is one day old or two days old. They can judge by the firmness of a tomato whether it’s worth 50 yen or 30 yen. This creates an atmosphere of fierce but honest competition. Shopkeepers rely on volume and reputation rather than high margins. They nurture loyal customers by consistently offering quality products at fair prices. In Tokyo, you might find a flawless peach displayed in a beautiful wooden box for 2,000 yen at a department store. It’s a symbol of beauty and status. In Tenjinbashisuji, you’ll see a cardboard box brimming with slightly bruised but delicious peaches, sold for 500 yen per bag. Osaka shoppers don’t care about packaging or perfect appearance—they care about flavor and being able to provide their family with dessert for a week at the cost of a cup of coffee. This philosophy applies across the board. Why pay extra for a brand-name t-shirt in a pristine boutique when you can get a perfectly serviceable one, stacked high with hundreds of others, for a third of the price? The value lies not in the brand but in the usefulness. This unwavering pursuit of value is the fundamental principle that keeps living costs low. It pushes vendors to cut overhead and inefficiencies, passing savings directly to consumers.

The Unspoken Language of Price Tags

The visual language of the street reflects this value-first mindset. Neatly printed, polished signs are rare. Instead, you encounter a jumble of handwritten signs, often on brightly colored paper, sometimes with crossed-out prices replaced by lower offers. This isn’t unprofessionalism; it’s a message. It says, “We’re not spending money on fancy marketing. We’re small, flexible, and offering you the best deal right now.” The prices can astonish outsiders: a freshly fried, perfectly tasty potato croquette for 30 yen; a small bag of tangerines for 100 yen; three pairs of socks for 500 yen. These are not just sale prices—they are everyday norms. Foreign visitors often see these as quaint novelties or fun treats to try. But for the thousands living in the apartments and small houses branching off the main arcade, these offerings are essential. That 30-yen croquette is a genuine part of tonight’s meal. The 100-yen fruit is tomorrow’s kids’ snack. People organize their daily routines and budgets around these prices. The street itself becomes an external pantry and fridge. The dense competition keeps prices low. If one butcher sells minced pork for 100 yen per 100 grams, another a mere twenty meters away will price it at 98 yen. This micro-competition across hundreds of storefronts drives prices downward, benefiting everyone.

The Daily Price Check: A Survival Ritual

This dynamic scene transforms how people shop. The idea of a large, once-a-week grocery haul at a hypermarket is largely foreign to the Tenjinbashisuji way. Instead, shopping is a daily—or almost daily—ritual. An elderly woman might stroll the street in the morning, not necessarily buying, but mentally taking stock. She checks prices on mackerel at three different fishmongers, compares vegetable stands for the best spinach deal, then returns in the afternoon with this knowledge to put together an affordable dinner. This method is fluid and adaptive. Dinner isn’t planned ahead but shaped by what’s fresh, plentiful, and inexpensive today. This close connection to the source of food and goods promotes resourcefulness and limits waste. People buy only what they need for the next day or two, confident they’ll return tomorrow to shop again. It’s a lifestyle that is not only more economical but also deeply in tune with the rhythms of the seasons and the market.

Beyond the Yen: The Social Currency of Tenjinbashisuji

If the street’s influence on living expenses stopped at merely offering low prices, it would be an impressive economic case study. However, its true significance to the community goes far beyond that. The arcade serves as a center of social interaction, generating a kind of wealth that cannot be quantified in yen. It fosters a sense of belonging and mutual support that is increasingly rare in modern urban life, creating a social fabric sharply contrasting with the polite anonymity often found in Tokyo.

“Maido!” – The Voice of Community Commerce

Step into any chain store or department store in Tokyo, and you’ll be met with a crisp, polite, and entirely impersonal “Irasshaimase!” (Welcome!). It’s a general broadcast aimed at everyone and no one in particular. Visit a family-run pickle shop in Tenjinbashisuji for the second time, and you’ll hear a warm, familiar “Maido!” This Osaka-ben phrase, roughly translating to “Thanks, as always,” is fundamentally different. It’s not a broadcast; it’s an acknowledgment. It means “I see you. I remember you. I appreciate your continued patronage.” It turns a simple purchase into a thread in an ongoing relationship. This one word unlocks the entire social dynamic of the shotengai. It lays the groundwork for mutual dependence: the shopkeeper relies on residents for their livelihood, and the residents depend on the shopkeeper for fair prices and quality products. This creates a space for human interaction that is both commercial and deeply personal. Vendors and customers can be seen bantering, joking, and sharing local news. A conversation about the price of bonito flakes might effortlessly shift to discussing a grandchild’s school exams. This is not pointless chatter; it’s essential community work. It’s how people maintain their connections. This sharply contrasts with the efficient, silent, and purely transactional atmosphere of Tokyo supermarkets, where the aim is to get in and out quickly with minimal social contact.

The Human Network: Your Neighborhood Safety Net

The bonds built through these daily interactions form a strong, informal social safety net. The tofu shop owner knows that Mrs. Sato buys a block of firm tofu every morning. If she doesn’t show up one day, he might notice. If she’s absent for two days, he might mention it to the butcher next door, who also hasn’t seen her. This isn’t idle gossip. In a country with a rapidly aging population, this informal neighborhood watch is an invaluable—and free—social service. It offers a layer of care and security that no government program could replicate. In Tokyo’s vast, anonymous apartment complexes, it’s possible for someone to become isolated without anyone noticing. But in the tightly-knit community around Tenjinbashisuji, your absence would be noticed. This feeling of being known, of belonging to a local ecosystem, offers profound psychological benefits. It alleviates the isolation that can be one of big-city living’s greatest challenges. This, too, has an economic dimension. It acts as a form of insurance. Knowing your neighbors and local shopkeepers means having a network to turn to in minor emergencies—whether borrowing soy sauce or asking someone to watch your apartment while you’re away. It’s a currency of trust and favors, built one “Maido!” at a time.

A Tale of Two Cities: Why This Doesn’t (Really) Exist in Tokyo

The existence of a place like Tenjinbashisuji is not merely a historical coincidence; it is a direct outcome of Osaka’s distinctive cultural and economic evolution. Understanding why such a place flourishes here—while being almost unimaginable in central Tokyo—gets to the core of the fundamental differences between Japan’s two major cities.

The Economics of Space and Style

The simplest explanation lies in the harsh economics of real estate. Land prices in central Tokyo are exorbitant, making it nearly impossible for small, low-margin, family-owned businesses to survive. Economic pressures thus favor upscale brands, large corporate chains, and businesses that can charge premium prices for their goods and services. A sprawling 2.6 km street devoted to selling 30-yen croquettes and 98-yen pork could not sustain itself on land in Ginza or Shinjuku. Beyond real estate, however, there is a deeper cultural divergence. Tokyo’s consumer culture largely values presentation, curation, and brand prestige. The shopping experience itself is part of the product—beautiful packaging, attentive and respectful service, and a pristine environment are all elements Tokyo consumers willingly pay extra for. Osaka’s culture, shaped by fierce mercantile competition, is far more pragmatic. Osakans are famously impatient with anything they see as pretentious fluff. They prioritize directness, honesty, and above all, a good deal. The raw, chaotic, and unapologetically functional atmosphere of Tenjinbashisuji perfectly reflects this mindset. It is a space stripped of all pretense, focused solely on transactions and relationships.

The Foreigner’s Misconception: Tourist Trap or Local Lifeline?

One of the biggest mistakes foreigners make is viewing Tenjinbashisuji through a tourist’s perspective. They may stroll a few blocks, snap photos of the colorful signs, try some takoyaki, and conclude it is simply a quirky attraction. But they miss the point entirely. While the street does attract tourists, especially near its southern end by Tenmangu Shrine, they are a secondary audience. The street’s primary role is to serve the daily needs of Kita-ku residents. As you walk north, away from the more tourist-oriented sections, the nature of the shops changes. You see fewer souvenir stalls and trendy cafes, and more hardware stores, clinics, traditional tea merchants, butchers, and shops selling practical household goods. This is the real street, the engine room of the local economy. It is a complete, self-contained ecosystem. A resident could, in theory, meet nearly all of their daily needs without leaving the arcade. They can get a haircut, see a dentist, buy groceries, have their shoes repaired, and buy clothes. This concentration of essential services operating under a competitive, high-value principle makes living in the area remarkably affordable.

The “Kechi” Myth: Frugal, Not Stingy

There’s a longstanding stereotype in Japan that people from Osaka are kechi, or stingy. Like most stereotypes, it oversimplifies a more complex and interesting reality. Osakans are not stingy; they are averse to waste. Paying more than something is worth is seen as foolish—a failure of judgment. Conversely, finding a good deal is a source of pride and a story to be shared. There is a performative aspect to it: people boast about the great bargain they found on fish or the discount they got on a coat. This isn’t about hoarding money; it’s about playing the commercial game and winning. This collective mindset creates a virtuous cycle. Because every consumer relentlessly seeks the best value, vendors are compelled to provide it. This culture of savvy consumerism, embodied by the shoppers of Tenjinbashisuji, acts as the city’s invisible hand, continually pushing down the cost of living for all.

Weaving the Shotengai into Your Osaka Life: A Practical Guide

For a foreigner relocating to Osaka, making Tenjinbashisuji part of your daily routine is the most effective way to reduce expenses and immerse yourself in the local culture. This requires shifting your mindset away from relying on a one-stop supermarket toward a more diverse, dynamic, and ultimately rewarding style of living.

Your New Grocery Store

The first step is to let go of the big weekly shopping habit. Your refrigerator will get smaller, and your shopping bag will become your daily essential. Begin by walking along the street and simply observing. Notice where the longest lines gather in the late afternoon—this usually signals a time sale with steep discounts on items that need to be sold by day’s end. Instead of buying all your produce from one stall, learn to mix and match. The stall at 2-chome might have the cheapest onions, while the one at 4-chome offers better carrots today. This might seem inefficient at first, but it soon becomes a natural and enjoyable routine. Embrace the specialists. Don’t buy your fish at a general grocery store; go to the fishmonger with ice piled high and a gruff but knowledgeable owner who can advise you exactly how to cook the sea bream that arrived that morning. Buy your tofu from a dedicated tofu shop, where it’s made fresh daily and priced far below packaged brands. This approach not only saves money but also greatly improves the quality of your food.

More Than Just Food: The A-to-Z of Daily Needs

Once you’ve mastered daily food shopping, broaden your scope. You’ll realize the street can supply almost everything. Need pharmacy items? There are several large, highly competitive drugstores along the arcade, often with sale bins near the entrance offering fantastic deals on soap, toothpaste, and laundry detergent. Looking for socks or a simple T-shirt? Skip the department store and explore one of the many clothing shops where items are stacked high and sold for a few hundred yen. Household goods? Choose from multiple 100-yen shops, hardware stores selling everything from lightbulbs to picture hooks, and traditional shops specializing in knives or pottery. Consolidating your purchases within this ecosystem will dramatically reduce your monthly miscellaneous expenses. Saving a few hundred yen here and there quickly adds up over time. It’s the difference between ending the month with a comfortable buffer and constantly feeling financially stretched.

Cracking the Code: How to Shop Like a Local

A few practical tips can smooth your experience. First, bring cash. While some larger stores accept cards, many smaller vendors are cash-only. It’s quicker and the local custom. Second, carry your own shopping bags—or several—since you’ll be making multiple small purchases and need sturdy bags. Third, don’t hesitate to engage. A simple “Konnichiwa” and a smile go a long way. If unsure about a price, just point and ask, “Kore, ikura?” (How much is this?). As your Japanese improves, try to build rapport with the vendors you visit regularly. Greet them, thank them, and become a familiar face. This is how you begin to develop the sought-after “Maido” relationship. It may not happen overnight, but once it does, you might find yourself receiving a little something extra in your bag—an extra croquette or a slightly bigger piece of fish. This omake, a small gift from the seller, is the ultimate sign you’ve been embraced by the community. It’s a reward far more valuable than the item itself.

The Future of the Shotengai and Osaka’s Identity

In an era dominated by online shopping and corporate megastores, places like Tenjinbashisuji can easily be seen as charming relics of a past time. Across Japan, thousands of smaller shotengai are struggling, with many storefronts closed and walkways deserted. Yet, Tenjinbashisuji persists, even flourishes. Its vast size, its association with a major shrine, and its location in a densely populated residential neighborhood have granted it a resilience that others lack. However, its greatest strength lies in its profound and unwavering connection to the core identity of Osaka itself. The street is the tangible expression of the city’s spirit: practical, unpretentious, community-oriented, and fiercely value-conscious. As long as the people of Osaka continue to value a good deal and friendly conversation over sterile convenience and brand prestige, Tenjinbashisuji will have its place. For any outsider seeking to understand what defines Osaka, and what makes it feel so distinct from the polished perfection of Tokyo, a stroll down this endless arcade offers more insight than any museum or guidebook. It is a living lesson in the city’s values. To truly understand this street is to realize that the real wealth of a city isn’t always found in its gleaming skyscrapers or Michelin-starred restaurants, but in its people’s ability to live well, connect with one another, and find joy and dignity in the simple, shrewd art of everyday bargaining.