In the heart of Osaka, a city that pulses with a vibrant, modern energy, there exists a world where wood and silk breathe, where stories of profound love and gut-wrenching sacrifice are told not by human actors, but by puppets. This is the world of Bunraku, a traditional Japanese puppet theater so artistically refined, so emotionally potent, that it has been designated a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. At the epicenter of this captivating art form stands the National Bunraku Theatre, a modern temple dedicated to a centuries-old tradition. To step inside is to leave the neon-lit streets of the Dotonbori district behind and enter a realm of high drama, exquisite craftsmanship, and resonant sound, a place where the soul of old Japan is given a voice and a body. Bunraku isn’t merely a puppet show; it is a complex, symphonic experience, a trinity of performance arts working in breathtaking unison to explore the deepest currents of human emotion. It is a journey into the heart of Japanese aesthetics, where subtlety carries immense weight and a single, silent gesture can convey a world of meaning. Here in Osaka, the birthplace and reigning capital of this art form, the National Bunraku Theatre offers a portal into this powerful narrative tradition, inviting you to witness a performance that will linger in your memory long after the final chord of the shamisen has faded.

While the National Bunraku Theatre offers a profound look into performing arts, you can also explore Osaka’s deep historical roots at the ancient Sumiyoshi Taisha shrine.

The Sacred Trinity: Voices, Strings, and the Unseen Hand

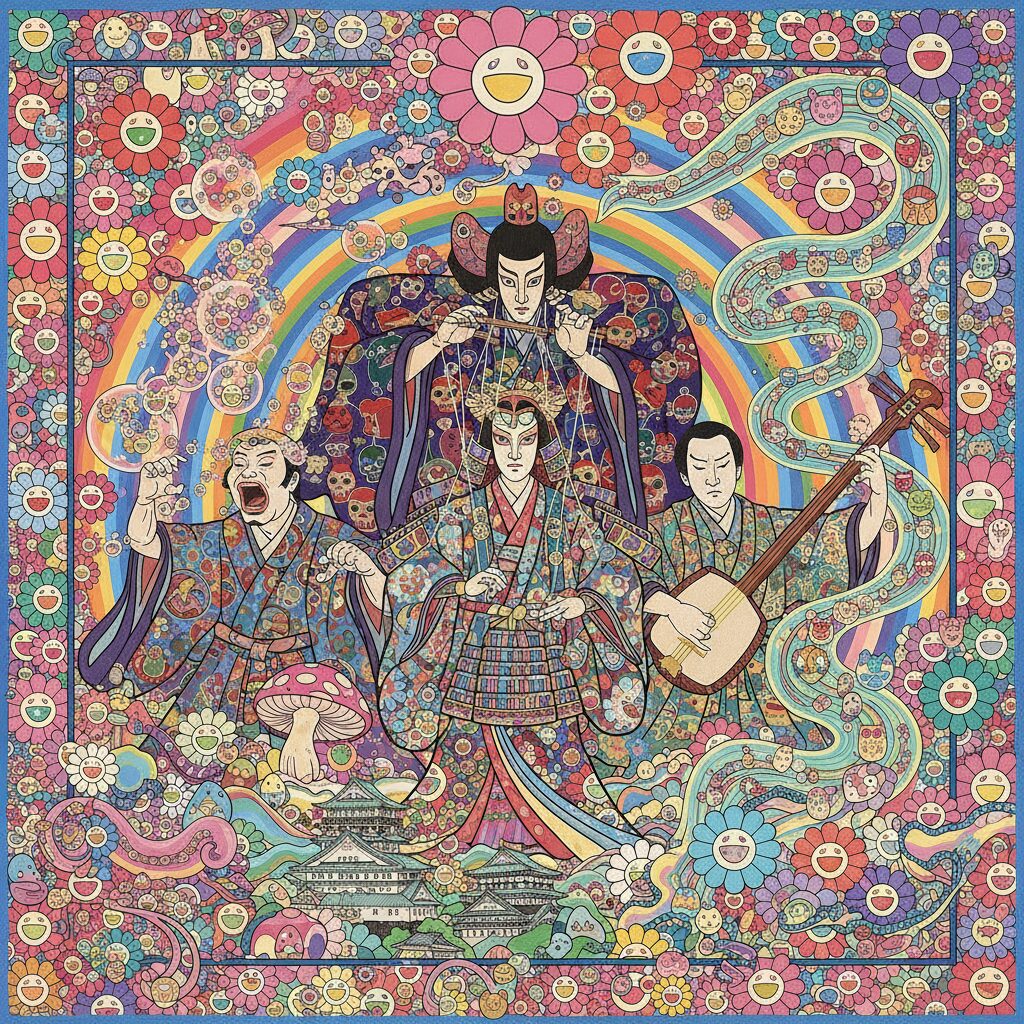

The magic of a Bunraku performance rests on a tripod of artistic disciplines, known as the san-gyo, or three professions. This collaboration is so seamless and deeply interconnected that separating them misses the essence entirely. They are the chanter (tayu), the shamisen player (shamisen-hiki), and the puppeteers (ningyozukai). Together, they create a single narrative voice, a unified force that breathes life into the inanimate. Watching them is witnessing a masterclass in collaboration, a testament to years of discipline sharpened to perfection.

First, there are the puppets, the ningyo, which serve as the visual heart of the drama. These are not the simple hand puppets of Western tradition. They are large, often two-thirds life-size, and astonishingly intricate. Each is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, with heads carved from cypress wood that, through ingenious mechanisms, can change expression instantly—a subtle frown, widened eyes of surprise, or a grimace of pain. Their costumes are exquisite, woven from rich brocades and silks, with each layer conveying the character’s status, personality, and emotional state. Yet the true genius lies in their manipulation. This is achieved through a unique three-person system called the sannin-zukai. Three puppeteers, dressed entirely in black (kurogo) to render them symbolically invisible, operate a single puppet. The lead puppeteer, the omozukai, is the master of this small troupe. This artist, often the only one whose face is visible, controls the head with their left hand and the puppet’s right arm with their right hand. The artistry required to express nuanced emotion through the tilt of a wooden head or the clenching of a small carved hand results from a lifetime of dedication. Traditionally, it takes ten years of training to master the feet, operated by the ashizukai, and another ten years as the hidarizukai, manipulating the puppet’s left arm. Only after two decades of near-anonymous work and learning to breathe and move as one with two other artists can a puppeteer earn the right to become an omozukai. This rigorous apprenticeship fosters an incredible, almost telepathic synergy. They don’t just move the puppet; they infuse it with a soul. They make it hesitate, sigh, and gaze with longing. In their hands, a doll becomes a being of profound emotional depth.

Next comes the voice of this world, the tayu. Positioned on a revolving platform to the side of the stage called the yuka, the tayu is the ultimate storyteller. This is not mere narration. The tayu performs every role, shifting from the delicate whisper of a young maiden to the thunderous roar of a vengeful samurai, from the sorrowful cries of a grieving mother to the objective voice of the narrator. This vocal style, known as gidayu-bushi, is a physically and emotionally demanding art form. It comes from the hara, the body’s center, a deep, guttural, and incredibly expressive form of chanting that conveys the raw essence of each character’s feelings. The tayu sits at a lectern, a thick script book before them, yet their performance is anything but a simple reading. They pour their entire being into the text, their face contorting with the characters’ emotions, their body tensing with the scene’s drama. It is a marathon of vocal and emotional endurance that leaves both performer and audience exhausted yet utterly spellbound.

Beside the tayu sits the third pillar of the trinity: the shamisen-hiki. The instrument used in Bunraku is the futozao shamisen, a larger, deeper-voiced version of the three-stringed lute. Its role goes beyond mere musical accompaniment. The shamisen is the heartbeat of the performance. It creates atmosphere—whether the tense silence before a duel, the gentle sound of falling snow, or the chaotic clamor of a bustling city street. Its sharp, percussive notes punctuate dramatic moments, while a lingering, mournful melody underscores scenes of tragedy. The shamisen player works in perfect harmony with the tayu, their music rising and falling with the chanter’s voice, anticipating emotional shifts and propelling the narrative forward. The sound is raw, powerful, and evocative, a character itself that speaks a language beyond words. This interplay between voice and string, between puppet and sound, is the foundational magic of Bunraku—an orchestra of emotion where every artist is a vital instrument.

The Stage: A Window into Another World

The National Bunraku Theatre in Osaka is unexpectedly modern, a sleek and elegant building that contrasts with the ancient art form performed inside. Opened in 1984, it serves as the official home and preservation center for Bunraku, underscoring the art form’s national significance and deep roots in this city. Within, the main hall is carefully designed to enhance the viewing experience and accommodate the unique demands of a Bunraku performance.

The stage itself is an intriguing blend of engineering and tradition. A notable feature is the set of partitions, or tesuri, that run along its length. More than mere decoration, these act as a functional barrier that conceals the puppeteers’ lower bodies, allowing them to move freely in a recessed area called the funazoko. This ingenious design ensures the audience’s full focus remains on the puppets, elevating them as the undeniable center of this dramatic world. The scenery, often beautifully painted—from the interior of a modest teahouse to a grand castle gate—is always crafted to support the puppets, never to overshadow them. Lighting is precisely executed to carve the puppets out of the darkness and emphasize the subtle flicker of emotion on their lacquered faces.

The atmosphere inside the theatre before a performance is one of quiet anticipation. The audience includes elderly longtime enthusiasts, students of Japanese culture, and curious international visitors. A shared respectful silence prevails, acknowledging the special experience about to unfold. Then, the sharp, percussive clap of the ki, or wooden clappers, signals the play’s start, and a profound stillness envelops the hall. The yuka turns, revealing the tayu and shamisen player, and with the first powerful shamisen note and resonant chant, the play’s world comes alive. For newcomers and especially non-Japanese speakers, the theatre provides an invaluable resource: an English earphone guide. This guide is far from a simple translation; it acts as a lifeline, offering real-time explanations of the plot, characters’ motivations, cultural context, and the symbolic meanings behind gestures or musical cues. It transforms what might be a visually stunning yet confusing spectacle into a deeply engaging and comprehensible drama. Using this guide is perhaps the most important advice for first-time visitors—it is the key to unlocking the complex narrative world of Bunraku.

Tales of Duty, Passion, and Fate

The stories of Bunraku are drawn from the rich fabric of Japanese history, literature, and folklore, mainly from the Edo period (1603–1868), when the art flourished. The repertoire is generally divided into two categories: jidaimono, or historical epics, and sewamono, domestic dramas focusing on the lives of ordinary townspeople. The former are grand narratives of samurai warriors, political intrigue, and legendary battles, filled with heroism and sacrifice. The latter, however, tend to be the most poignant and relatable for modern audiences, as they delve into the timeless conflicts of the human heart.

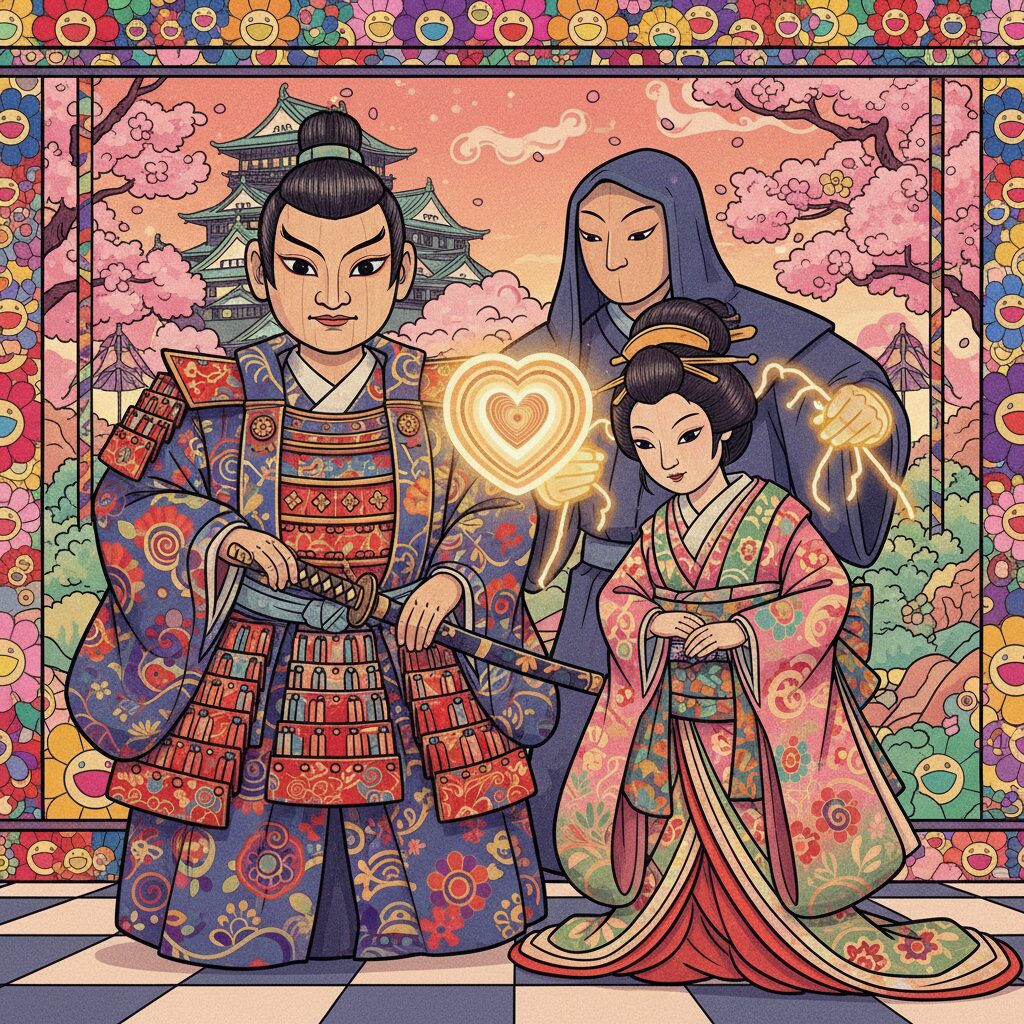

At the heart of many sewamono plays lies the tension between giri and ninjo. Giri can be understood as social obligation, duty, or the intricate web of responsibilities owed to family, society, and feudal superiors. Ninjo represents personal feelings, human emotion, love, and passion. In the rigidly structured society of feudal Japan, these two forces often clashed intensely, providing the fertile ground from which Bunraku’s most powerful dramas arise. Characters frequently find themselves torn between the desires of the heart and the demands of society, a struggle that often ends in tragedy.

Perhaps the most famous Bunraku play, closely connected to Osaka, is Sonezaki Shinju (The Love Suicides at Sonezaki), written by the renowned playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon. It tells the true story of Tokubei, an orphaned clerk, and Ohatsu, the courtesan he loves. Betrayed by a friend and publicly disgraced, Tokubei is unable to fulfill his obligations or restore his honor. Bound by circumstance and their profound love, the couple chooses to unite only in the afterlife. They make their way to the woods at the Sonezaki shrine and end their lives together. This story, with its raw portrayal of love and despair, caused a sensation when first performed in 1703. It struck such a chord with the public that it reportedly sparked a wave of real-life copycat suicides, prompting authorities to temporarily ban plays on the topic. Witnessing Sonezaki Shinju at the National Bunraku Theatre is to feel the heartbeat of old Osaka, grasp the social pressures and romantic ideals of a bygone era, and see how a tale told through puppetry can evoke an emotional depth as profound as any live-action tragedy.

These stories are far more than mere historical artifacts. They offer powerful explorations of universal themes—love, betrayal, honor, sacrifice, and the individual’s struggle against an inflexible society. The wooden puppets on stage become vessels for these grand emotions, and though their plight is centuries old, it still moves audiences to tears.

A Practical Guide to Your Bunraku Experience

Attending a performance at the National Bunraku Theatre is a highlight of any cultural trip to Osaka, and with a bit of planning, it becomes a very accessible experience. The theatre is conveniently situated in the Nippombashi district, just a short walk from Nippombashi Station, which is served by the Sennichimae and Sakaisuji subway lines. It is also within easy walking distance of the lively Namba area, making it easy to include in a day of sightseeing.

It is important to note that Bunraku performances are not held year-round. The theatre usually hosts performances for several weeks at a time, with intervals in between. The typical schedule includes runs in January, April, a summer season from late July to early August, and November. Therefore, checking the National Bunraku Theatre’s official website well ahead of your visit is crucial. There, you will find the performance calendar, program information, and links to book tickets online. Popular shows can sell out quickly, so booking in advance is highly advisable.

Full Bunraku performances can be quite lengthy, often lasting four hours or more with intermissions. While this offers an immersive experience in the art form, it can be a significant time commitment for first-time visitors. Luckily, the theatre offers a fantastic and highly recommended alternative: hitomaku-miseki, or single-act tickets. These tickets go on sale at the box office on the day of the performance and allow you to watch just one act of a longer play, usually lasting between 60 to 90 minutes. This serves as an excellent introduction to Bunraku, offering a concentrated dose of drama and artistry without being overwhelming, and it is also more affordable. It allows you to sample the experience and decide if you’d like to attend a full program in the future. Simply check the schedule for the timing of each act and arrive at the theatre a little before ticket sales begin for the act you want to see.

During the performance, standard Japanese theatre etiquette applies—silence is key, and photography or recording is strictly forbidden. Intermissions, however, are a lively part of the experience. This is the time to stretch your legs, browse the gift shop for souvenirs and books about the art form, or partake in a classic Japanese theatre tradition: the makunouchi bento. These beautifully arranged lunch boxes are sold at the theatre and are meant to be enjoyed during the main intermission. Savoring a bento in the theatre lobby is a culturally authentic way to complete your visit and engage with the experience like a local.

Bunraku’s Echoes Through Osaka

One of the most rewarding experiences of watching Bunraku in Osaka is how the world of the plays extends beyond the theatre into the city streets. Situated in Nippombashi, the theatre places you at the intersection of several captivating districts where the echoes of the stories you’ve just seen on stage linger in the air. A short walk away is Kuromon Ichiba Market, a vast, covered marketplace famously known as “Osaka’s Kitchen.” Here, you can fully immerse yourself in the lively, chaotic atmosphere of the merchant class, who were both the audience and subjects of many sewamono plays. The sights and sounds of fishmongers calling out their wares and vendors grilling fresh scallops forge a sensory connection to the vibrant urban scenes portrayed on the Bunraku stage.

For a deeper immersion, head to the nearby Namba district and explore Hozenji Yokocho. This narrow, stone-paved alley, adorned with traditional lanterns and the moss-covered statue of the deity Fudo Myo-o, resembles a perfectly preserved Edo-period movie set. It serves as an atmospheric time capsule, evoking the mood and setting of many Bunraku dramas. Taking a stroll here after a performance, especially in the evening when the lanterns emit a warm glow, feels like stepping directly into the world you just left behind at the theatre.

Yet, the most profound pilgrimage for any Bunraku fan is a visit to Tsuyunoten Shrine, better known as Ohatsu Tenjin. This modest, unassuming shrine, hidden among the modern buildings of the Umeda district, is the actual site of the tragic climax of Sonezaki Shinju. It is said to be where the real Tokubei and Ohatsu ended their lives. Today, the shrine is a place where lovers come to pray for eternal happiness, with statues of the doomed couple standing as a memorial. Standing here after witnessing their story unfold through the movements of puppets is an incredibly moving experience. It bridges the gap between art and life, between a 300-year-old tale and the present moment, forging a profound and tangible connection to the cultural heart of Osaka.

The Unbroken Thread: A Living Tradition

In a world dominated by fleeting digital entertainment, Bunraku stands as a testament to patience, discipline, and the enduring power of storytelling. Achieving mastery in any of its three disciplines demands a lifetime of steadfast dedication, a commitment that is increasingly uncommon in today’s world. The artists who practice this craft are more than performers; they are living links in an unbroken chain of tradition, passing down skills and stories from generation to generation. The Japanese government, through its support of the National Bunraku Theatre, acknowledges the art form as a vital part of the nation’s cultural identity and actively works to preserve it.

Continuous efforts are made to nurture new artists and attract younger, more diverse audiences. Collaborations with contemporary artists, detailed programs offered in multiple languages, and an accessible single-act ticket system are all components of a strategy designed to keep Bunraku vibrant and thriving rather than relegated to a museum artifact. It endures because the stories it tells—of love constrained by society, honor demanding the ultimate sacrifice, and the quiet suffering and defiant passions of ordinary people—are deeply human. While the medium is stylized and the language archaic, the emotions remain as raw and relevant today as they were three centuries ago.

The Resonance of a Wooden Heart

A visit to the National Bunraku Theatre is more than a mere cultural excursion; it is an act of attentive listening. It invites you to slow down, watch with focused concentration, and let a story unfold at its own deliberate, powerful rhythm. You might not catch every word, but you will sense the sorrow in a puppet’s bowed head, the fury in the sharp twang of a shamisen string, and the desperation in the chanter’s trembling voice. You will leave the theatre with these emotions etched in your memory. The performance ends, the lights brighten, and you step back into the electric pulse of modern Osaka, yet something from that other world lingers with you. It is the resonance of a wooden heart that, for a few hours, beat with fierce and undeniable vitality. It is the echo of a tradition that continues to speak, with profound eloquence, to the soul of anyone willing to listen.