You see it before you even arrive. A tower, not quite Eiffel, not quite anything else, piercing the sky above a low-slung neighborhood of weathered concrete and tangled wires. This is the Tsutenkaku, the unblinking eye of Shinsekai. As you get closer, the smells hit you—the sweet, heavy scent of frying batter from a hundred kushikatsu shops, the faint but persistent aroma of stale beer and old tobacco clinging to the pavement, the metallic tang of pachinko parlors exhaling clouds of manufactured excitement. Then the sounds: the cheerful, looping jingles from claw machine arcades, the aggressive invitations from restaurant barkers, the low rumble of conversations from men huddled in shogi clubs, a world away from the tourists snapping pictures of the giant fugu lantern. This is Shinsekai, Osaka’s “New World,” an area that feels paradoxically, stubbornly, stuck in the past. For the tourist, it’s a vibrant, retro theme park, a colorful dive into the Showa Era’s cheerful excess. It’s a place for cheap eats, quirky photos, and a taste of “old” Japan.

But for those of us who live in Osaka, who navigate its daily rhythms and understand its unspoken codes, Shinsekai presents a different, more complex question. What happens when the last train pulls away, taking the sightseers back to their hotels in Umeda or Namba? What is the lifeblood of this neighborhood when the performance of nostalgia ends for the day? The truth is, Shinsekai isn’t a museum. It’s a living, breathing, and often struggling organism. Its nostalgic facade is a thin veneer stretched over a reality of economic hardship, deep-seated community, and a raw, unfiltered humanity that is quintessentially Osaka. It’s a place that rejects the polish of Tokyo and wears its scars with a defiant pride. To understand Shinsekai is to understand the soul of Osaka itself—not the sanitized version sold in guidebooks, but the city as it truly is: pragmatic, resilient, and unapologetically messy. This isn’t a guide on what to see in Shinsekai. This is an exploration of what Shinsekai is, and what it tells us about the city we call home.

To truly grasp the city’s pragmatic soul beyond Shinsekai, one must also explore the authentic daily life found in Osaka’s Kuromon Market.

The Two Faces of Tsutenkaku Tower

The Tsutenkaku Tower stands as both the literal and symbolic heart of Shinsekai. It shapes the skyline, attracts the crowds, and its presence defines the neighborhood’s character. Yet, the tower holds two very different meanings depending on your viewpoint—whether you’re looking out from its observation deck or gazing up from the streets below.

The Beacon of Dreams, The Shadow of Reality

When the original Tsutenkaku was erected in 1912, it was an awe-inspiring emblem of ambition. Its name, meaning “Tower Reaching Heaven,” briefly lived up to that promise. Part of an expansive amusement complex called Luna Park, inspired by Coney Island, it reflected a modern, industrial, forward-thinking Osaka that saw itself as Japan’s rival to the great Western cities. The tower’s design combined elements of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe, making a bold statement of cultural fusion and technological innovation. It symbolized a future that was bright, exciting, and full of endless possibilities.

That envisioned future, however, never fully materialized. The park deteriorated, the original tower was dismantled for the war effort, and the neighborhood gradually changed. The tower standing today, rebuilt in 1956, serves as a monument to that initial dream but casts a long shadow over a very different reality. Now, when you pay the fee and ascend in the elevator, you’re entering a carefully crafted experience. You look out over the vast Osaka metropolis, rub the feet of the Billiken statue—a quirky, grinning deity imported from America who became the area’s guardian—and make a wish for “things as they ought to be.” It’s a tidy, safe, and somewhat surreal tourist attraction.

Yet, when you return to street level, you step into the world under the tower’s shadow. Here, things are not “as they ought to be,” but simply “as they are.” The streets are a hectic mix of gaudy signs, peeling paint, and the faint scent of desperation masked by frying oil. The grand vision of the original Luna Park has given way to the gritty reality of survival. The irony of the Billiken, a deity of manufactured happiness, overseeing a neighborhood characterized by its raw and often harsh reality is striking. The tower sells a dream of Osaka, but the streets below reveal its unfiltered truth.

Day vs. Night: The Shifting Atmosphere

Shinsekai’s dual nature is most evident in the shift from day to night. During the day, especially on weekends, the neighborhood puts on its liveliest face. The main streets are crowded with tourists from Japan and abroad, couples on dates, and families with children. The atmosphere buzzes with carnival-like energy. Kushikatsu restaurants, with their bright signs and playful mascots, thrive. The rules are clear and repeated: “No double-dipping the sauce!” Arcades blast J-pop as visitors try to win oversized stuffed animals from claw machines.

This daytime Shinsekai feels like a performance, an interactive stage where everyone plays a role. Shopkeepers act as cheerful hosts, tourists engage as eager consumers, and the neighborhood itself seems like a living theme park dedicated to a romanticized past.

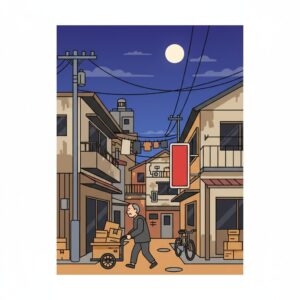

But as the sun sets, a profound transformation takes place. Tourist buses leave, the crowds thin, and a different cast of characters appear. The glow of the neon signs takes on a more somber, melancholic tone. Shadows lengthen in the narrow side streets. This is when the real Shinsekai comes alive. The regulars, the old-timers, the neighborhood’s longtime residents, reclaim their space. The quiet, dimly lit tachinomi (standing bars) and horumon (grilled offal) joints—largely ignored by daytime visitors—fill with familiar faces.

The soundscape shifts entirely. Cheerful pop music gives way to the relentless clatter of pachinko balls, rough laughter and slurred arguments spill from cheap izakayas, and a focused silence descends in the shogi and go parlors. Night reveals Shinsekai not as a tourist destination, but as a home—a sanctuary for those on the margins, where the performance ends and the unscripted reality of everyday life begins.

A Living Museum of Faded Glory: The Showa Myth

Much of Shinsekai’s contemporary charm is rooted in the idea of “Showa Retro.” The Showa Era (1926-1989) is often remembered with a golden-tinted nostalgia, a period of post-war recovery, rapid economic growth, and an innocent, optimistic spirit. Shinsekai is promoted as the ultimate Showa experience, a place to step back in time. However, this nostalgia is a complex and often manufactured product.

The Appeal of Manufactured Nostalgia

Walking through Shinsekai, you are immersed in the aesthetics of the past. Hand-painted movie posters from the 1950s and 60s decorate the walls of a closed theater. Faded tin signs advertising long-discontinued beer and medicine brands remain deliberately in place. The fonts on restaurant signs are blocky and old-fashioned. Even the famous pufferfish lantern of the Zuboraya restaurant (now sadly closed, a casualty of the pandemic) felt like a relic from another era.

This curated decay holds a strong attraction. For younger Japanese, it offers a link to a past they never lived through, a time seen as more authentic and human-scaled than today’s digital world. For foreign tourists, it satisfies the desire for an “authentic” Japan, something that feels more genuine than Tokyo’s gleaming skyscrapers. But this raises an important question: whose nostalgia is it?

For the people who live and work in Shinsekai, especially the older generation, this isn’t “retro.” It’s just life. Peeling paint on a building isn’t an aesthetic choice; it’s a sign of a lack of funds for repairs. The worn-out furniture in a small bar isn’t a curated vintage piece; it’s the same furniture that has been there for forty years. The neighborhood’s appearance is less a celebration of the past and more a direct result of decades of economic stagnation. The “Showa Retro” that tourists pay to experience is the lived, ongoing reality of a community largely left behind by the economic boom the era is meant to symbolize.

The Unspoken Economics of Kushikatsu

Kushikatsu, deep-fried skewers of meat and vegetables, is Shinsekai’s official fuel. The well-known rule against double-dipping into the communal sauce pot is repeated constantly, a fun and quirky aspect of local culture for visitors. But behind this simple culinary tradition lies a story of class and economic necessity.

Kushikatsu is fundamentally laborers’ food. It originated here to serve the thousands of day laborers working at nearby docks and construction sites. It had to be cheap, quick, and calorie-dense. A few skewers and a glass of inexpensive beer was a fast, affordable way to end a long day of physical labor. That essence remains today. Despite many restaurants’ tourist-friendly makeovers, kushikatsu is still one of the cheapest hot meals available in the area.

Competition among the dozens of kushikatsu shops is fierce. Standing on the main street, you are approached by barkers from every direction, each claiming the best flavor, crispiest batter, or lowest prices. This isn’t a friendly food festival rivalry; it’s a daily fight for economic survival. The divide is clear between the large, polished chains with English menus and bright lighting aimed at tourists, and the smaller, older establishments tucked into side streets. These places are often grimy, the air thick with meal smoke, and their clientele almost entirely local. The regulars who have visited for decades, the old men sitting at the counter nursing a single drink for an hour. Dining in one of these spots reveals a different kind of commerce — one based on loyalty and routine rather than novelty and volume.

Janjan Yokocho: The Pulse of Old Osaka

If Shinsekai’s main streets are its public face, Janjan Yokocho is its heart. This narrow, covered shopping arcade runs along the neighborhood’s eastern edge, linking it to the Dobutsuen-mae area. Its name comes from the shamisen’s sound that once enticed customers. Today, the soundtrack has changed, but the atmosphere remains just as strong.

A walk through Janjan Yokocho is a full sensory immersion. The alley is so narrow you can almost touch both sides at once. The air carries a dense mix of aromas: the sweet and savory scent of doteyaki (beef sinew stewed in miso) bubbling in large pots, the sharp tang of pickled vegetables, pervasive cigarette smoke, and the faint sweetness of spilled beer. The alley hosts a unique ecosystem of businesses catering to a distinct local clientele.

Here are shogi and go parlors — not tourist attractions. Peering inside, you see rows of older men, bent over their boards in intense, almost reverential silence. The only sounds are the sharp clicks of pieces on wood and occasional groans of frustration or sighs of defeat. These clubs serve as vital social centers for a demographic often isolated, representing one of the last bastions of a particular kind of male public life that has almost vanished from modern Japan. Alongside them are tachinomi bars, some so small they hold only five or six people standing shoulder-to-shoulder, and horumon-yaki restaurants serving grilled offal, a cheap and nutritious working-class staple. Janjan Yokocho is Shinsekai distilled: a place of simple pleasures, deep-rooted community, and complete lack of pretense.

The People of the New World: Beyond the Stereotypes

A neighborhood means nothing without its people, and the residents of Shinsekai are as integral to its identity as the Tsutenkaku Tower. They challenge simplistic stereotypes and embody the multifaceted character of Osaka.

The “Oっちゃん” (Ossan): Guardians of Tradition

The most prominent and audible figures in Shinsekai are the Osaka “ossan”—middle-aged or elderly men. To outsiders, they may appear intimidating. Often loud, speaking in a thick, guttural Kansai-ben dialect, their faces bear the marks of a tough life. You’ll find them gathered outside pachinko parlors in the morning, waiting for the doors to open, or sitting on park benches with a can of chu-hi at ten in the morning, or holding court at a standing bar counter in the afternoon.

The common stereotype portrays them as gruff, drunk, and somewhat uncouth. However, dismissing them as such overlooks the real essence. These men are the living history of the neighborhood. Many were day laborers for whom Shinsekai’s affordable food and entertainment were designed. Their lives are deeply tied to the economic highs and lows of this part of the city. Pachinko parlors and tachinomi (standing bars) are not just leisure spots; they serve as community centers, living rooms, and support networks. In a society that often prizes quiet conformity, the Shinsekai ossan stands out as a symbol of unapologetic individuality.

Engaging with them offers a lesson in a different form of Japanese social etiquette. The polite, indirect communication common in Tokyo is absent here. An ossan might address you, even a foreigner, with a boldly direct question: “Anata doko kara kitan?” (“Where are you from?”). This isn’t meant to be intrusive but is a straightforward attempt at connection. They might offer unsolicited advice, share long, rambling stories, or invite you to buy a drink. This social code thrives on immediate, unfiltered human connection. It can be surprising but seldom malicious. This is the spirit of Osaka—direct, practical, and harboring a strong belief that every stranger is just a friend yet to share a drink.

The Invisible Residents: Life on the Margins

It’s impossible to discuss Shinsekai honestly without recognizing its immediate southern neighbor: Nishinari, especially the area called Airin-chiku (formerly known as Kamagasaki). This is Japan’s largest hub for day laborers and consequently hosts its greatest concentration of homeless people. For decades, men from across Japan have come here seeking temporary construction work. The area is dotted with doya, cheap flophouses renting rooms by the night or week.

Though tourist maps neatly outline Shinsekai, the two neighborhoods actually blend into one another. The socio-economic realities of Airin-chiku quietly drive Shinsekai’s economy. The 100-yen vending machines selling lukewarm coffee, the extremely cheap bento boxes, the low-cost entertainment—all cater to this demographic. Walking through Shinsekai, you witness the public face of a community struggling with entrenched poverty, aging, and social isolation. The men sleeping on park benches or sifting through trash for recyclables are not anomalies; they are part of the neighborhood’s ecosystem.

For many Japanese, and certainly for many foreigners, such visible poverty can be shocking. Japan projects an image of prosperity, orderliness, and a largely middle-class society. Shinsekai and Nishinari shatter that illusion. They exemplify the Japanese concepts of “tatemae” (public facade) and “honne” (true feelings). Most of Japan operates under strict tatemae. Shinsekai displays raw, unavoidable honne. It refuses to hide its problems and instead forces a confrontation with a side of Japan many prefer to overlook.

The Shopkeepers: Daily Struggles to Survive

The small, family-run businesses form the backbone of the neighborhood. They act as a bridge between old Shinsekai and the new, tourist-driven economy. Picture an elderly woman running a tiny udon shop tucked away in a narrow alley for fifty years. Her hands are rough from decades of kneading dough and washing dishes. Her shop holds just a few stools, and its walls are stained dark brown from years of cooking steam and cigarette smoke.

Her feelings about the changes are likely mixed. The influx of tourists brings much-needed business for survival. Yet, it also brings a very different kind of customer. Tourists don’t understand the unwritten rules; they endlessly photograph their food and don’t engage in the easy banter she shares with regulars, like the ossan who orders the same bowl of kitsune udon daily. Her true loyalty lies with those regulars, the community that has supported her for decades.

These shopkeepers wage a battle on two fronts: against large, well-funded chain restaurants slowly encroaching on their territory, and against the march of time itself. Many are aging with no successors to take over. Each small, independent shop closing is a tear in the neighborhood’s social fabric. Their resilience, quiet strength, and commitment to their craft amid immense pressure embody a subtle form of heroism. They are preserving a piece of Osaka’s soul, one bowl of noodles or one skewer of kushikatsu at a time.

The Unspoken Rules of a Neighborhood on the Edge

Navigating Shinsekai means grasping a set of unspoken social norms that differ markedly from those in other parts of Japan. Here, typical etiquette is often set aside, replaced by a more direct and sometimes volatile local code.

Navigating the Social Code

Across most of Japan, unsolicited interaction with strangers is uncommon, and making direct eye contact on the subway is generally considered a social misstep. In Shinsekai, however, these boundaries are more flexible. Eye contact can serve as an invitation, a nod might spark a conversation, and a shared laugh at something absurd on the street can forge a brief connection. Yet, this openness carries a certain unpredictability. A friendly gesture may be warmly received or met with a curt dismissal or suspicious glare. The key is to read the situation carefully, remain open but cautious, and know how to politely disengage if the interaction turns uncomfortable.

Personal space is also more fluid here. The streets and shops are crowded, bringing you into close contact with many different people. Don’t be surprised if someone strikes up a conversation while you’re waiting in line or at a tachinomi counter. This is rarely an intrusion; rather, it is often the local way of passing the time and acknowledging shared space—a sharp contrast to the invisible barriers people maintain in cities like Tokyo.

Additionally, Shinsekai largely operates on a cash-only economy. While sleek, modern kushikatsu chains might accept credit cards, the small, decades-old establishments that define the area almost never do. This isn’t merely technological lag; it reflects a mindset. Business here is tangible, immediate, and personal—transactions involve exchanging physical currency, usually accompanied by a gruff “ookini” (thank you in Osaka dialect). Prices are already very low, reflecting the economic reality of the clientele. This is not a place for haggling; the price is final, representing an honest, if narrow, margin for the server.

“Dangerous” Osaka: Deconstructing the Myth

Shinsekai, along with neighboring Nishinari, has long held a reputation across Japan as “dangerous” (abunai). This notion deserves careful unpacking, especially for foreign residents. When a Japanese person calls an area “dangerous,” they often do not mean violent crime in the Western sense.

Is Shinsekai dangerous? If you’re concerned about being randomly mugged or assaulted, the answer is overwhelmingly no. Such street crime remains exceedingly rare here. The “danger” of Shinsekai is more about social tension and unpredictability—it involves encounters that disrupt Japan’s carefully maintained social harmony.

You’ll see people visibly intoxicated at any hour, overhear loud, heated street arguments, and encounter individuals with untreated mental health issues. You’ll face a level of poverty and homelessness rarely seen in most other parts of Japan. This raw, unfiltered human struggle can be deeply unsettling. For someone used to the pristine order of Kyoto or the corporate polish of Tokyo, this atmosphere can feel jarring and easily mistaken for direct physical threat.

The real skill in navigating Shinsekai lies not in self-defense, but in situational awareness and empathy. It’s about recognizing that the gruffness and chaos stem from hardship, not malice. It means moving through the area with respect and without judgment. This is a crucial distinction from places like Tokyo’s Kabukicho, where edginess often feels commercialized—a crafted danger maintained by organized groups for profit. Shinsekai’s grit is authentic: the grit of lives lived on the economic edge, marked equally by desperation and resilience.

What Shinsekai Teaches Us About Osaka

Ultimately, Shinsekai is more than just a neighborhood; it is a microcosm of Osaka’s character—a living testament to the city’s history, mindset, and its fundamental resistance to the dominant culture of Tokyo.

The Spirit of “Naniwa”: Resilience and Pragmatism

“Naniwa,” the ancient name for Osaka, is often used to describe the city’s distinctive spirit. It embodies the spirit of merchants rather than samurai; pragmatism instead of protocol; resilience over refinement. Shinsekai represents perhaps the purest modern expression of the Naniwa spirit. It began as a grand and ambitious dream—the Luna Park and the Tsutenkaku—that ultimately did not succeed. But rather than being demolished and forgotten, it adapted. Piece by piece, it transformed into something new: a hub for the working class, a place offering inexpensive entertainment and simple comforts. It endured.

This captures the essence of Osaka’s pragmatism. When the recent tourist boom arrived, the neighborhood did not undergo wholesale gentrification that erased its identity. Instead, it adapted pragmatically once again. New, shiny restaurants opened alongside the old, weathered establishments. Souvenir shops appeared next to 100-yen stores. Shinsekai welcomes tourist money, but largely on its own terms, without sacrificing its core identity. It bends, but does not break. This capacity to absorb setbacks, adapt to changing fortunes, and continue with a stubborn, unsentimental determination to survive is at the heart of the Naniwa spirit.

A Rejection of Tokyo’s Polish

To truly grasp Osaka, one must understand its relationship with Tokyo—a rivalry stretching back centuries, though now mostly aesthetic and cultural. Tokyo is the city of “tatemae”: sleek surfaces, constant renewal, and corporate perfection. Old buildings are consistently torn down to make way for the new. Neighborhoods are curated and branded. The city relentlessly pursues a kind of flawless, impersonal modernity.

Shinsekai stands as a monumental, defiant rejection of this philosophy. It is a neighborhood deeply and openly flawed, making no effort to conceal it. The rust, grime, chaos, and visible social problems are not viewed as failures to be cleaned away but as part of life’s texture. It is messy, human, and unapologetically so. This reflects a broader Osaka mindset that often regards Tokyo as sterile, cold, and superficial. Osakans value “honne” over “tatemae,” substance over style, and lively, messy, good-natured debate over polite, sterile silence. Shinsekai is the city’s id—a place where its most fundamental traits are fully displayed.

The Foreigner’s Place in the “New World”

So where does a foreign resident fit into this complex tapestry? In Shinsekai, invisibility is impossible. Unlike in the more cosmopolitan districts like Umeda or Shinsaibashi, here you clearly stand out as an outsider. Tourists are treated as commodities, temporary sources of income, but a foreign resident becomes a curiosity. Your presence unsettles the local equilibrium.

Yet, this visibility can be a chance. If you approach the neighborhood with humility, respect, and a genuine desire to understand, you may find a rare kind of acceptance uncommon in more reserved parts of Japan. The key is to shed the role of passive observer. Don’t merely photograph the intriguing old men; if the moment feels right, try striking up a conversation. The best way to understand Shinsekai is to join its rhythm. Find a small, cramped tachinomi bar, squeeze into a counter spot, and order a beer and some doteyaki. Put your phone away. Listen to the conversations around you. Watch the interactions between shopkeeper and regulars. This simple act—being fully present without the shield of a camera or guidebook—is how you begin to see beyond the gritty exterior and glimpse the resilient, fiercely human heart of Shinsekai, and by extension, the true soul of Osaka.