There’s a rhythm to Osaka that is undeniably electric. The city pulses with a vibrant, relentless energy, a symphony of neon signs, sizzling street food, and the cheerful cacophony of crowds navigating its famous districts. Yet, just a few subway stops from the brilliant chaos of Namba or Umeda, the city’s heartbeat slows to a gentle, meditative hum. Step out of Tanimachi 6-chome Station, and you emerge into a different current of time. Here, the air feels softer, the light seems to filter through a historical lens, and the narrow streets whisper stories of a past that has been carefully, lovingly preserved. This is the Karabori district, a rare pocket of pre-war Osaka, and it is here, amidst the weathered wooden facades and winding alleyways, that one can discover one of Japan’s most profound culinary traditions: Shojin Ryori.

Shojin Ryori is often translated as “Japanese vegetarian cuisine,” but this simple label barely scratches the surface of its depth and meaning. It is more accurately described as devotion cuisine, a spiritual practice rooted in the principles of Zen Buddhism. This is food as meditation, a way of eating that seeks to nourish not only the body but also the spirit, fostering a sense of balance, gratitude, and connection to the earth. It is a quiet rebellion against excess, a celebration of subtlety, and a testament to the extraordinary flavors that can be coaxed from the simplest of ingredients. To experience Shojin Ryori in a neighborhood like Tanimachi 6-chome is to embark on a journey that transcends mere dining. It is an immersion into a philosophy, an art form, and the very soul of a more contemplative Japan, hidden in plain sight within the bustling metropolis of Osaka.

For a different taste of Osaka’s culinary soul, consider exploring the city’s legendary standing sushi bars in Kyobashi.

The Soul of Shojin Ryori: A Philosophy on a Plate

Before even sitting down to eat, it is helpful to understand the quiet philosophy guiding every element of Shojin Ryori. The term “shojin” means devotion, the focused pursuit of a path, while “ryori” simply means cuisine. This food is not born of trends or fleeting culinary fads; its origins lie deep in Zen Buddhist monasteries, where monks developed a way of eating that aligned with their spiritual teachings. The core principle is ahimsa, or non-violence, which calls for the exclusion of all meat and fish. Yet, the philosophy goes far beyond a mere plant-based diet.

Traditionally, Shojin Ryori also avoids pungent alliums like garlic, onions, and scallions. In Buddhist beliefs, these ingredients are considered overly stimulating, disrupting the calm, focused mind needed for meditation. The challenge, then, is to create profound and satisfying flavors without relying on these common staples of global cuisine. This limitation is not a constraint but an inspiration, compelling the chef to explore the subtle, intrinsic tastes of vegetables, grains, and seaweeds with remarkable creativity and skill. The result is a cuisine that speaks softly rather than loudly, revealing its complexity gradually and rewarding a mindful palate.

At the heart of this culinary art is the “rule of five,” a principle that ensures every meal is a harmonious balance for both body and senses. This rule requires the inclusion of five distinct colors (green, red, yellow, black, and white), five essential flavors (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami), and five traditional cooking methods (simmering, grilling, steaming, frying, and raw). It is not just an aesthetic guideline but a holistic approach to nutrition, ensuring balanced nutrient intake and an engaging dining experience. Every element on the plate serves a purpose, contributing to a larger, interconnected whole. This mindfulness extends to preparation as well. The chef embraces the philosophy of “mottainai,” a deep cultural sense of regret over waste. Every part of an ingredient is utilized, from the peel of a daikon radish, finely sliced for pickles, to the water used to rehydrate shiitake mushrooms, which becomes an essential component of the dashi broth. This respect for ingredients is a form of gratitude, acknowledging the life force of the plant and the earth that nurtured it.

Tanimachi 6-chome: A Neighborhood Wrapped in Time

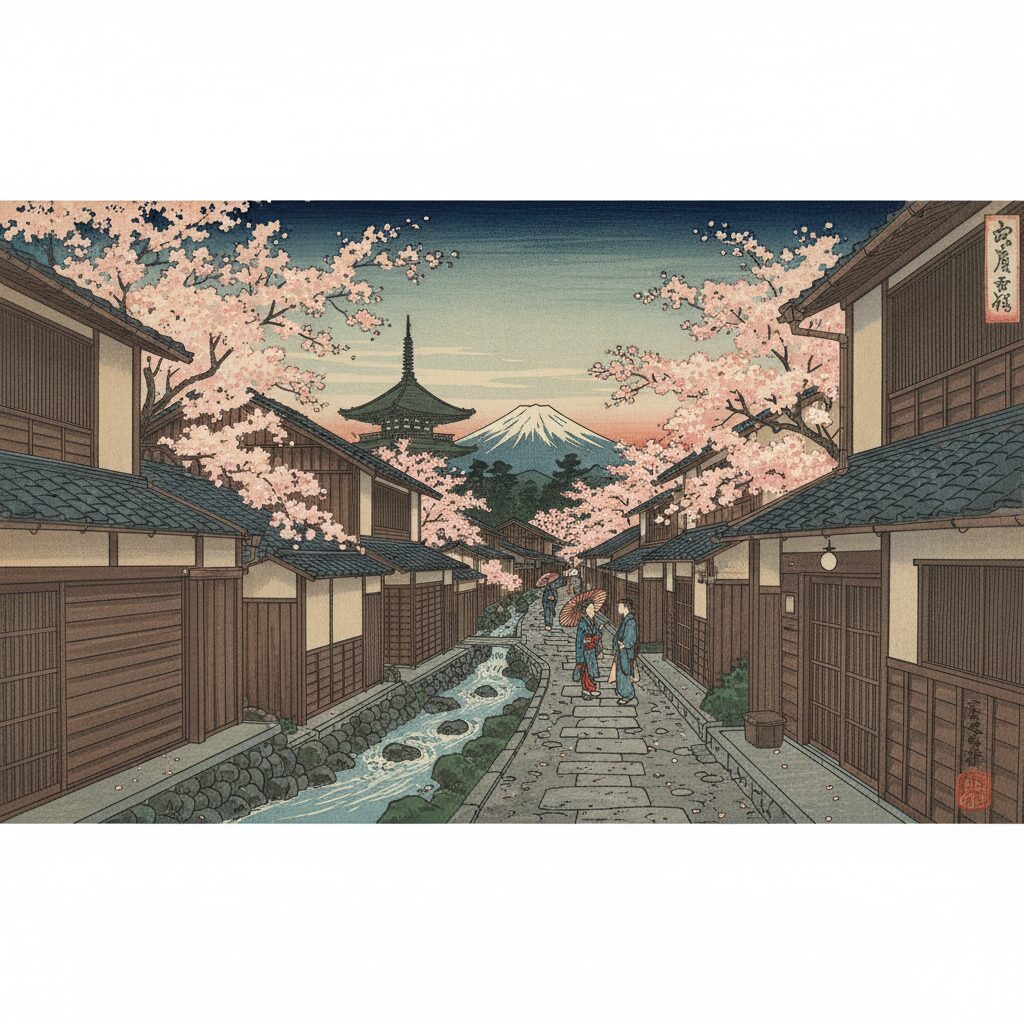

Choosing to seek Shojin Ryori in the Tanimachi 6-chome area is intentional. The neighborhood itself serves as the perfect introduction to the meal, embodying the values the cuisine represents: history, simplicity, and a quiet, resilient beauty. While much of Osaka was devastated during World War II, this district miraculously remained intact, preserving a labyrinthine network of narrow alleyways and traditional wooden townhouses known as `machiya`. Walking here feels like stepping through a portal. The noise of the city’s main streets fades away, replaced by the soft rumble of a bicycle on a stone path, the chime of a shopkeeper’s door, and the distant laughter of children.

At the heart of the neighborhood is the Karabori Shopping Arcade, or `shotengai`. Unlike the polished, brightly lit arcades in more central city areas, Karabori feels authentically lived-in. Its covered street is lined not with big-name brands, but with small, family-run businesses that have thrived for generations. There’s a tofu maker who has honed their craft over decades, a shop selling fragrant teas from across Japan, a potter shaping the very bowls you might later use, and a vendor of traditional Japanese sweets, whose delicate creations change with the seasons. The atmosphere is warm and unhurried. Shop owners greet passersby, neighbors stop to chat, and the entire arcade hums with a gentle, communal energy. It’s a place that encourages you to slow down, look closer, and appreciate the small details.

Veering off the main arcade, you’ll enter the `roji`, the impossibly narrow alleys winding between the old houses. Here, the sense of history is tangible. The dark, weathered wood of the `machiya` rises on either side, their latticed windows and tiled roofs forming a beautiful tapestry of texture and shadow. Potted plants line the walkways, adding touches of green to the muted palette. You might catch a glimpse of a hidden courtyard garden, a `tsuboniwa`, a miniature landscape designed to capture the essence of nature in a small enclosed space. These are the very views a Shojin Ryori meal might evoke. The neighborhood is not a museum; it is a living, breathing community that has chosen to preserve its character rather than surrender to modernity. This deep respect for heritage and embrace of a slower pace of life create the ideal mental and emotional space to fully appreciate the mindful meal that awaits you.

A Symphony of the Earth: The Shojin Ryori Experience

To dine on Shojin Ryori is to engage in a carefully choreographed ritual, a sequence of courses that unfolds with the grace and precision of a formal ceremony. The experience begins as soon as you slide open the door to one of the region’s hidden treasures, often a small restaurant nestled within a renovated `machiya`.

The Setting

You will be invited to remove your shoes at the `genkan`, or entryway, a simple gesture that signifies the shift from the outside world to a serene space. The interior typically embodies minimalist elegance. The floor is covered with tatami mats, whose fresh, grassy scent serves as a subtle form of aromatherapy. Low wooden tables are arranged with `zabuton` cushions for seating. The walls may be finished with a soft, earthen plaster and decorated with a single piece of calligraphy or a simple flower arrangement, `ikebana`, reflecting the current season. Light gently filters through `shoji`, paper screens that diffuse sunlight into a soft, ethereal glow. Often, your table overlooks a small, meticulously maintained garden. This connection to nature, even in miniature form, is essential. It serves as a constant reminder of the source of the food you are about to enjoy.

The Unfolding Courses

A Shojin Ryori meal is usually served as a multi-course `kaiseki`, with each dish presented in sequence. The meal begins not with a bold statement, but with a gentle whisper. A typical first course is `goma-dofu`, or sesame tofu. This is different from the soy-based tofu you might know. It is made by painstakingly grinding sesame seeds into a paste, then combining it with water and a natural thickener like `kuzu` starch. The result is a small, pristine cube with a texture that is incredibly creamy and smooth, melting on the tongue with a deep, nutty, and slightly earthy flavor. It is often served chilled, with a tiny dot of freshly grated wasabi and a drop of light soy sauce, providing a delicate contrast that awakens the palate.

Following this might be the `suimono`, a clear soup that embodies the soul of Japanese cuisine. The broth, or `dashi`, in Shojin Ryori is a masterpiece of subtlety. Without the use of bonito flakes found in conventional dashi, it draws its profound umami from high-quality `kombu` (kelp) and dried shiitake mushrooms, often soaked overnight to gently extract their essence. Floating in this crystal-clear, fragrant broth might be a handcrafted ball of mashed tofu and vegetables, a carved carrot in the shape of a maple leaf for autumn, or a sprig of yuzu peel releasing a burst of citrus aroma as you lift the bowl. To sip this soup is to grasp the Japanese aesthetic of purity and refinement.

Subsequent courses display a variety of cooking techniques. You might be served `nimono`, a simmered dish. Perhaps a piece of tender daikon radish, slowly cooked in kombu dashi until translucent and fully infused with savory flavors, served alongside a piece of `kabocha` pumpkin whose natural sweetness has been enhanced by gentle simmering. Then, a grilled dish, `yakimono`, may arrive. A classic example is `dengaku`, featuring a slice of firm tofu or a piece of eggplant scored, grilled until tender, and brushed with a sweet and savory miso glaze that caramelizes under heat, creating a pleasing contrast of textures and flavors.

Shojin-style tempura offers a delightful crunch. The batter is light and delicate, used to fry an exquisite array of seasonal vegetables and `sansai`, or wild mountain vegetables. In spring, you might find fiddlehead ferns and bamboo shoots, their slightly bitter notes a welcome taste of the mountains. The skill lies in frying them just enough to create a crisp shell while perfectly steaming the vegetable inside, preserving its natural flavor and color. The meal is completed by perfectly cooked rice, a bowl of rich miso soup, and a small selection of `tsukemono`, or Japanese pickles. These pickles are not merely condiments; they are an essential part of the meal, providing a sharp, salty, or sweet counterpoint that cleanses the palate and aids digestion. They represent the art of preservation and the wisdom of utilizing every part of the harvest.

The Art of Presentation

Throughout the meal, you will notice the profound attention given to visual aesthetics. The food is not simply placed on a plate; it is arranged on a carefully chosen collection of ceramics. Each bowl, dish, and platter is selected for its color, texture, and shape to complement the food it holds. A deep green, mossy glaze might be chosen to highlight a vibrant red vegetable, while a rustic, earthy clay dish may cradle a pale, delicate piece of tofu. The principles of asymmetry and the use of negative space are paramount. The arrangement is never crowded, allowing each element to be appreciated individually while contributing to the overall composition. It is, in every sense, edible art—a feast for the eyes that invites contemplation before the first bite is taken.

Practical Guidance for Your Culinary Pilgrimage

Embarking on a Shojin Ryori experience is simple, but a bit of preparation can make the journey smoother and more fulfilling, especially for first-time visitors.

Getting There

Tanimachi 6-chome Station is your starting point. It’s conveniently served by two subway lines: the purple Tanimachi Line and the light green Nagahori Tsurumi-ryokuchi Line, making it easily reachable from major hubs like Umeda, Tennoji, and Shinsaibashi. After arriving, follow signs toward the Karabori Shopping Arcade. Exits 3 and 4 are generally the best entry points for exploring the historic core of the district. The area is very walkable; take your time to wander and get lost in its charming side streets.

Making Reservations

This is perhaps the most important advice. Shojin Ryori restaurants, particularly the authentic, high-quality ones in areas like Tanimachi, are often small, with only a few tables. Many operate strictly by reservation. This is because preparation is highly labor-intensive, and chefs source and prepare ingredients according to the exact number of guests expected. Arriving without a reservation will likely result in disappointment. It’s strongly recommended to book at least several days or even weeks in advance, especially during peak seasons. If you’re not comfortable making a call in Japanese, your hotel concierge can be very helpful. Some restaurants also accept reservations through online platforms.

Dining Etiquette

Though the atmosphere is welcoming, following a few etiquette points will enrich your experience and show respect for the culture. After removing your shoes, place them neatly together, pointing toward the door. When sitting on the tatami floor, the formal posture is `seiza` (kneeling), but foreigners may sit cross-legged or with legs to one side if more comfortable. Before eating, it’s customary to cleanse your hands with the provided hot towel, or `oshibori`. When eating, hold your rice and soup bowls with one hand while using chopsticks with the other. Most importantly, try to finish all the food served—this shows the highest respect for the chef and the ingredients themselves, reflecting the `mottainai` spirit.

Seasonal Considerations

One of the most enchanting features of Shojin Ryori is its strong connection to the seasons. The menu reflects what is at its peak natural bounty at that time. Spring celebrates new growth with tender bamboo shoots (`takenoko`), bitter but tasty mountain vegetables (`sansai`), and delicate cherry blossoms as garnish. Summer features cooling ingredients like cucumber, eggplant, and juicy tomatoes, often served in jellied broths (`nikogori`) to refresh the body. Autumn highlights a rich harvest, with chestnuts (`kuri`), sweet potatoes, an abundance of mushrooms, and vibrant persimmons. Winter focuses on warming, nourishing root vegetables such as daikon radish, burdock root (`gobo`), and taro, often served in hearty, slow-simmered dishes. Appreciating this seasonal rhythm adds depth to your meal, connecting your dining to the broader cycles of nature.

Beyond the Meal: Exploring the Karabori District

Your journey into the world of Shojin Ryori shouldn’t end once you’ve settled the bill. The whole Karabori district extends the experience—a place to stroll, observe, and soak in the atmosphere of old Osaka. After your meal, take a leisurely walk through Karabori Shotengai again. With the flavors still lingering on your palate, you may find yourself appreciating the produce at the greengrocer in a new way. Stop by a traditional confectionery to sample `wagashi`, seasonal sweets whose designs reflect the same philosophy as your meal.

Don’t hesitate to explore the `roji`. These narrow alleys hold the neighborhood’s true secrets. You might discover a beautifully preserved `machiya` transformed into a creative space like `Ren-So-Ro`, featuring small art galleries, artisan workshops, and quirky cafes. These venues showcase the community’s commitment to revitalizing its historic buildings. You may also come across a small, quiet neighborhood shrine where locals pay their respects—a peaceful spot for reflection away from even the gentle bustle of the arcade.

If you have more time, a longer walk or a short subway ride can take you to Shitennoji Temple, one of Japan’s oldest Buddhist temples. Though not directly in the neighborhood, a visit offers deep historical context for the spiritual roots of the Shojin Ryori you just experienced. Exploring the temple grounds, observing rituals, and sensing the profound history can help connect the dots between the food, its philosophy, and the faith that inspired it.

A Photographer’s Perspective: Capturing the Essence

Through the lens, Tanimachi 6-chome and the world of Shojin Ryori unfold as a dream of textures, light, and tranquil moments. The aim is not merely to document but to convey the feeling—the `wabi-sabi` aesthetic of imperfect, fleeting beauty that saturates everything. In the alleys, morning light illuminates the dark, oiled wood of the `machiya`, creating a striking interplay of light and shadow. The wood’s grain, the texture of a weathered wall, the intricate patterns of roof tiles—these details tell the story. Focus on the small elements: a lone bicycle resting against a wall, a line of laundry fluttering in the breeze, the reflection in a shop window.

Inside the restaurant, the challenge shifts to capturing stillness. The light is often soft and low, filtering gently through the shoji screens. This calls for a high ISO and a steady hand. Rather than using flash, which would disrupt the mood, embrace the shadows. The beauty is found in the subtle gradients of light on a lacquered bowl, the steam rising from a cup of tea, the vivid, natural colors of the food set against the muted ceramics. Compose your shots to highlight negative space, the artful emptiness as vital as the subject itself. Capture the chef’s hands as they carefully plate a dish, or the serene look of your dining companion as they savor a bite. This is not commercial food photography; it’s about capturing a moment of mindfulness—a visual poem reflecting the quiet harmony of the experience.

A Gentle Farewell: Carrying the Stillness With You

A meal of Shojin Ryori in Tanimachi 6-chome is an experience that stays with you long after you’ve slipped your shoes back on and stepped into the bustle of Osaka. It’s more than just a memory of delicious food; it’s a feeling, a state of being. You leave not feeling heavy or full, but light, refreshed, and deeply nourished. A sense of calm settles within you—a quietude born from the peaceful setting and the mindful act of eating.

This is the true gift of Shojin Ryori. It teaches you to be attentive, to find beauty in simplicity, and to cultivate gratitude for the food you eat and the hands that prepared it. It’s a reminder that even in a city as vibrant and fast-moving as Osaka, there are pockets of profound stillness waiting to be uncovered. The spirit of this meal, and this timeless neighborhood, is something you carry with you. It’s an invitation to slow down, savor the moment, and find the extraordinary within the ordinary—a quiet echo of serenity to hold onto long after you’ve returned home.