They say every city has a shadow, a place where the postcards fade and the raw, unfiltered pulse of life beats a little louder. In Osaka, that place is Nishinari Ward. Whisper the name to a local, and you’ll likely get a flicker of recognition, a raised eyebrow, maybe even a cautionary tale. For decades, Nishinari has been branded as Japan’s most notorious neighborhood, a hub for day laborers, the homeless, and a certain gritty underbelly that stands in stark contrast to the nation’s polished image of safety and order. But here’s the thing about shadows: they hold more depth and nuance than the blinding light allows you to see. As a traveler who has chosen to plant roots in this vibrant, chaotic city, I’ve learned that the stories you hear are only the first chapter. The truth of living in Nishinari is a tangled, fascinating, and deeply human narrative that deserves to be told not with fear, but with open eyes. This isn’t a guide to a tourist spot; this is a deep dive into the reality of a place that is, for a certain kind of soul, one of the most compelling places to live not just in Osaka, but in all of Japan. It’s a district of profound contrasts, where rock-bottom rents sit beside unparalleled transport access, where Showa-era nostalgia bumps up against the hard realities of modern poverty, and where a powerful sense of community thrives amidst the struggle. So, let’s peel back the layers of myth and misconception and take a real look at the pros and cons of calling Nishinari Ward home.

For a deeper look at the unique character of nearby districts like Showa-cho, which shares some of this nostalgic atmosphere, read our guide for remote workers finding their flow in Showa-cho, Osaka.

Unpacking the Legend: What’s the Real Story Behind Nishinari?

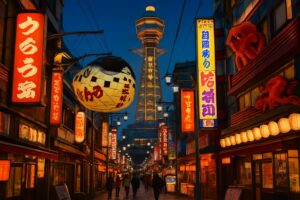

To understand Nishinari today, you need to rewind the clock. Its reputation wasn’t established overnight. The heart of the ward’s notoriety lies in a specific district once known as Kamagasaki, now officially called Airin-chiku. After World War II, Japan was engulfed in a frenzy of reconstruction and economic growth. This monumental effort required a vast labor force, and Kamagasaki became a hub for day laborers from across the country. They gathered here seeking jobs in construction, shipping, and manufacturing, helping to build the foundations of modern Osaka. Simple, affordable lodgings called doya emerged to accommodate them, creating a unique, transient community. It was a place defined by hard work, tough living, and a certain rugged masculinity. For decades, this system functioned smoothly. Men would assemble early in the morning, get hired for the day, and return at night with cash to spend at local eateries and bars. However, as Japan’s economy evolved and the post-war construction boom faded, demand for manual labor diminished. The men who had built the city grew older, left without work, family support, or escape. This is the root of Nishinari’s present-day struggles. The Airin-chiku area became a focal point for concentrated poverty, unemployment, and aging, all highly visible. This history is imprinted in the very architecture: narrow streets, low-rise buildings, and numerous single-room accommodations—all designed for function rather than family life. The street atmosphere can be overwhelming: the clatter of pachinko balls spills out of brightly lit parlors, the savory smoke of grilled horumon (offal) lingers in the air, and low murmurs from men sitting on plastic crates create a constant background. It feels worlds apart from the polished consumerism of Umeda or the neon-lit fantasy of Dotonbori. This is not a place that plays to the crowd; it is unapologetically itself. Myths about danger often arise from this raw reality. Seeing men sleeping on the street or drinking in the morning can shock those used to Japan’s typical public order. Riots have occurred here, though the last major one was decades ago, stemming from frustrations over labor conditions and police actions. Today, the “danger” is mostly misunderstood. Violent crime is extremely rare, as in almost all of Japan. The real issue is not physical threat but confronting social problems generally hidden away. It is a place of visible hardship, and that visibility can be mistaken for hostility. In truth, life for most residents, especially beyond the core Airin-chiku block, is quiet and ordinary.

The Unbeatable Pros: Why You Might Actually Love Living in Nishinari

Once you look beyond Nishinari’s formidable reputation, you begin to notice the strong currents of appeal that attract people here. And to be straightforward, the biggest draw is the price. Nishinari is undoubtedly the most affordable place to live in all of Osaka City. We’re not talking about a minor discount; we’re talking about an entirely different financial reality. While a small studio apartment in a popular central ward like Chuo or Kita might cost you over 70,000 yen a month, in Nishinari, you can find similar or even larger spaces for 30,000 to 40,000 yen. For students, working holiday visa holders, or anyone looking to save money while living in a major city, this is a game-changer. This affordability extends to every part of life. Vending machines selling drinks for 50 yen are common sights. Tiny eateries offer hearty bowls of udon or curry for just a few hundred yen. Local supermarkets, especially the legendary Super Tamade with its neon-lit storefronts and surprisingly low prices, make grocery shopping a lesson in frugality. This financial freedom lets you enjoy more of what Osaka has to offer, freeing up your budget for travel, hobbies, or simply living with less financial pressure.

But Nishinari’s appeal goes far beyond just saving money. It is a living museum of Showa-era Japan. For those who feel nostalgic for a Japan that is rapidly fading, Nishinari is a treasure trove. The shotengai, or covered shopping arcades, are the heart of the community. Walking through Tsurumibashi Shotengai, one of Osaka’s longest, transports you back in time. Elderly shopkeepers sell homemade pickles, fresh fish, and traditional sweets from stalls that have been in their families for generations. The air buzzes with vendors’ friendly calls and locals chatting as they shop daily. It’s a stark contrast to the sterile experience of chain stores. Retro kissaten (coffee shops) with velvet seats and siphon coffee makers hide away on side streets, perfect for spending a relaxed afternoon. Old-fashioned public baths, or sento, still thrive here as social hubs where neighbors catch up while soaking in the hot water. Living in Nishinari offers a chance to experience a more genuine, community-centered lifestyle that is growing rare in Japan’s big cities. This is a place where character is engraved into every cracked pavement and weathered storefront.

Beyond its charm and affordability, Nishinari has a huge practical advantage: transportation. It’s one of the best-connected wards in Osaka, anchored by the Shin-Imamiya station complex, a hub for JR and Nankai railways. From here, you can reach the heart of Namba in just two minutes. The JR Osaka Loop Line swiftly connects you to major hubs like Tennoji, Osaka Station (Umeda), and Kyobashi. The Nankai line offers a direct, fast, and inexpensive link to Kansai International Airport (KIX), making travel easy. Additionally, the Dobutsuen-mae subway station serves the main Midosuji line—the backbone of Osaka’s subway system—and the Sakaisuji line, giving you one-transfer access to Shinsaibashi, Yodoyabashi, and even Kyoto to the north. For such rock-bottom rents, Nishinari offers connectivity that rivals neighborhoods demanding three times as much in rent. This unique combination is its secret weapon.

Lastly, the food scene deserves mention. Osaka is known as Japan’s kitchen, but Nishinari offers a culinary experience that is grittier, cheaper, and arguably more soulful. This is the undisputed kingdom of horumon and kushikatsu. Standing-only bars serve sizzling plates of grilled offal, perfectly seasoned and washed down with cheap beer. The aroma around the train tracks is savory and thick. For newcomers, it might seem intimidating, but for adventurous eaters, it’s paradise. This is food for the people—unpretentious and deeply satisfying. You’ll find bento boxes packed with a day’s worth of calories for just a few hundred yen, alongside vendors selling deep-fried meat and vegetable skewers that make ideal snacks. Here, you can dine like royalty on a pauper’s budget.

The Unvarnished Cons: Facing the Realities of Nishinari

An honest discussion about Nishinari inevitably involves acknowledging its challenges. It would be misleading to describe it as a misunderstood utopia. The same factors that make the area affordable also contribute to conditions that some may find difficult. The most notable downside is the unavoidable, daily presence of visible poverty. Nishinari has a higher concentration of homeless and elderly, unemployed men than anywhere else in Japan. You will witness people sleeping on cardboard in parks and beneath overpasses, as well as men openly struggling with alcoholism and other health issues. This is not an abstract idea; it forms part of the neighborhood’s everyday visual reality. For many, especially those from cultures where such social issues are less visible, this can be emotionally challenging and unsettling. There is a tangible sense of struggle and despair in certain parts of the ward that you simply won’t encounter elsewhere in the city. This is not a judgment but a fact that any potential resident must approach with empathy and understanding. Closely related to this is the matter of cleanliness. Despite Japan’s reputation for spotless streets, Nishinari often diverges from this norm. Around Shin-Imamiya and Dobutsuen-mae, streets are sometimes littered with trash, empty cans, and cigarette butts, and the scent of stale alcohol and urine can linger in alleyways. While residential areas tend to be cleaner, the central commercial districts lack the immaculate maintenance seen elsewhere. Some buildings are rundown, and graffiti is more frequent. For those who value the usual Japanese standards of public cleanliness and order, Nishinari can come as a shock. Then there is the social stigma attached to the area. Nishinari’s reputation is deeply rooted in the Japanese collective consciousness. If you tell someone from outside Osaka that you live in Nishinari, you will likely be met with surprise, concern, or disbelief. They may ask if it’s safe or why you would choose to live there. Although this perception often stems from outdated stereotypes, it remains a genuine social obstacle. Constantly having to justify your choice of neighborhood can be exhausting. This stigma might not impact your daily life within the ward, where a strong sense of local pride exists, but it does affect your interactions with broader society. It serves as a reminder that you live in a place many regard as the lowest rung of the social ladder. Finally, regarding lifestyle, Nishinari lacks modern amenities and a certain type of nightlife. If your ideal weekend involves sipping craft lattes in trendy cafes, browsing designer boutiques, or dancing in stylish nightclubs, you’ll have to look beyond the ward’s borders. The local entertainment is more old-fashioned: pachinko parlors, gritty izakayas frequented by elderly men, karaoke bars with peeling posters, and small cinemas screening older films. Shopping is practical, focused on daily needs rather than fashion. While this authenticity appeals to some, it may feel limiting to others. Though you have excellent access to Osaka’s broader entertainment districts, much of that scene isn’t found right on your doorstep.

Navigating Nishinari: A Practical Guide for Prospective Residents

It is important to recognize that Nishinari is not a uniform area. Living experiences here can differ greatly from one street to another. If you are seriously thinking about moving here, it’s essential to do thorough research and explore the various neighborhoods within the ward. The notorious Airin-chiku (Kamagasaki) is a small zone just south of Shin-Imamiya Station, where the day-laborer culture is most prevalent, featuring doya hotels and social welfare centers. While it’s interesting to walk through, it is generally not recommended as a place to live for newcomers, especially single women. The atmosphere is intense, and the living conditions are very basic. However, just a short distance away, the environment changes drastically. Heading south toward Tengachaya or Kishinosato, you’ll find quiet, pleasant residential neighborhoods filled with family homes, small apartment buildings, and local schools. The streets are cleaner, and the vibe is much calmer. Tengachaya Station is an excellent transport hub, providing access to the Nankai and Sakaisuji lines, making it a very convenient option. This area offers a great balance: you can enjoy Nishinari’s low rents while living in a more traditional and peaceful setting. Another good choice is the area around Tamade. Known for the headquarters of the famous Super Tamade supermarket, this neighborhood is a lively, working-class residential area with a vibrant shotengai, many restaurants, and a down-to-earth atmosphere. It combines convenience with strong local character. Before committing to a lease, spend several days walking through these different zones. Visit at various times—a weekday morning, a Saturday afternoon, a weeknight—to truly understand the rhythm of each place. What feels vibrant and exciting to one person may seem chaotic and overwhelming to another. For everyday life, embrace the local institutions. Make Super Tamade or the neighborhood shotengai your regular grocery stop. You’ll save money and connect with the community. When it comes to safety, common sense is key. While violent crime is rare, petty theft can occur. Don’t leave your bicycle unlocked and stay aware of your belongings in crowded areas. At night, stick to well-lit main streets, especially near stations. The most important advice is to be respectful and considerate. You are a guest in a community with a deep and complex history. Avoid taking photos of people without permission, be courteous in your interactions, and don’t treat the neighborhood as a poverty tourism attraction. Learning some basic Japanese phrases will greatly help you show respect and build rapport with local shopkeepers and neighbors.

The Changing Face of Nishinari: Gentrification on the Horizon?

For decades, Nishinari seemed like a place stuck in time. However, in recent years, winds of change have started to blow. The most significant driver has been the surge in tourism to Japan. Developers and entrepreneurs, recognizing the area’s prime location and affordable property prices, have begun to move in. On the border with the wealthier Tennoji ward, the sleek and modern Hoshino Resorts OMO7 hotel now dominates the neighborhood, standing as a striking symbol of this new era. This development has attracted a different type of visitor to the area. Backpacker hostels and trendy guesthouses have emerged, transforming old buildings into stylish accommodations for international travelers drawn by the promise of an “authentic” and “edgy” experience. Nowadays, you are just as likely to see a group of European tourists with rolling suitcases as an elderly day laborer. This influx of tourism and investment is a double-edged sword. On one side, it brings fresh money and vitality to a long-neglected area, creating jobs and possibly leading to better infrastructure and cleanliness. On the other side, it carries the threat of gentrification. There is a genuine worry that rising property values may displace long-term, low-income residents and the small, family-run businesses that give Nishinari its unique charm. Will the gritty horumon stands be replaced by craft beer bars? Will the shotengai lose its soul to souvenir shops? This tension is tangible. The “new” Nishinari is gradually encroaching on the “old.” For a potential resident, this means the Nishinari you move into today could look quite different five or ten years from now. It’s a dynamic, evolving environment. This process of change can be captivating to experience firsthand, yet it also carries a bittersweet feeling for what might be lost. Living here now means having a front-row seat to a story of urban transformation unfolding worldwide—a struggle between preservation and progress, character and capital.

Who is Nishinari For? (And Who Should Look Elsewhere?)

So, after considering the positives, negatives, and complexities, who is the ideal Nishinari resident? This neighborhood perfectly suits the adventurous, open-minded, and budget-conscious. Whether you’re a student stretching your funds, an artist seeking unconventional inspiration, or an experienced traveler who values grit over gloss, Nishinari might be your ideal place. It’s for those who prioritize function—like excellent transportation—over immaculate appearances. It’s for people eager to experience a raw, authentic side of Japan without tourist-focused pretensions. If you’re resilient, unshaken by challenges, and open to living in a community facing significant social issues, you will gain a profoundly authentic and enriching experience. You’ll save a substantial amount of money, reside in a location with access to the entire Kansai region, and become part of a neighborhood with a strong, unmistakable character. However, Nishinari is not suitable for everyone. Families with young children may find the lack of clean, modern parks and the general environment in central areas concerning. While more family-friendly areas like Kishinosato exist, the ward overall is not primarily designed for family life. If you highly value cleanliness, quiet, and order, Nishinari may be a constant source of stress. Those seeking a modern, convenient lifestyle with trendy cafes, gyms, and boutiques on every corner should look elsewhere—Umeda, Fukushima, or the areas around Tennoji would be a better match. Most importantly, if the sight of homelessness and public intoxication makes you feel unsafe or very uncomfortable daily, choosing another neighborhood is advisable. Being honest with yourself about your tolerance and what you need from your living environment is the key to making the right decision.

Final Thoughts: Embracing the Diamond in the Rough

Nishinari is a paradox—a place of both immense hardship and remarkable spirit. It is a neighborhood many Japanese people are quick to overlook, yet it embodies a resilience and sense of community that are increasingly rare. Living in Nishinari means challenging your own assumptions, learning to look beneath the surface, and connecting with Japan on a deeply human level. It’s not the easiest or prettiest place to live. Some days, the grit feels overwhelming, and the visible struggles weigh heavily. But on other days, the simple kindness of a local shopkeeper, the incredible flavor of a 100-yen skewer, or the effortless convenience of catching a train to anywhere in minutes makes you feel as though you have uncovered the city’s best-kept secret. Nishinari acts as a mirror, reflecting a side of Japan’s economic story often ignored—the story of the men who built the dream but were left behind when it came true. Living here teaches empathy, reminding you that a city is more than its gleaming skyscrapers and famous landmarks; it is a complex tapestry of human lives, woven with threads of both triumph and hardship. Ultimately, choosing to live in Nishinari comes down to one simple question: Are you seeking comfort, or are you searching for character? If it’s the latter, you may find this notorious neighborhood is not a shadow to fear but a diamond in the rough, waiting to be discovered.