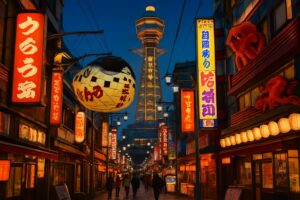

Walk out of Ogimachi Station, or maybe Tenjinbashisuji Rokuchome, and you feel it before you see it. It’s a low, persistent hum. Not the sterile whoosh of a Tokyo subway, but a sound full of texture: the clatter of bicycle bells, the sizzle of oil, the rhythmic, gravelly calls of vendors, and the shuffling feet of a thousand people on a mission. You’re at the entrance of the Tenjinbashisuji Shopping Street, a 2.6-kilometer covered arcade that isn’t just a collection of shops. It’s the central nervous system of daily life in northern Osaka. Many guides will tell you it’s the longest in Japan. That’s a fact, a piece of trivia. But it’s also the least interesting thing about it. What they don’t tell you is that this street is a living textbook on how to understand Osaka. It’s where the city’s soul—pragmatic, boisterous, obsessed with value, and deeply human—is on full display. Forget the tourist maps for a moment. We’re not here to sightsee. We’re here to learn how to live, how to shop, and how to decode the unwritten rules of Osaka’s magnificent, chaotic, and utterly essential main street. This is your practical guide to becoming part of the Tenjinbashi beat.

To truly appreciate the value-driven soul of Osaka showcased here, you might also be interested in a detailed breakdown of living costs in the Tennoji area.

The Unspoken Rules of the Arcade Aisle

Before buying anything, you first need to learn how to move. In a city like Tokyo, movement follows strict, unspoken rules upheld by collective pressure. People queue single file for trains, stand on one side of escalators, and walk in predictable patterns. Tenjinbashisuji, however, operates on a different, more organic principle: managed chaos. It may seem like a free-for-all, but there’s a method to the madness, a dance you must master.

The Human Current: Navigating the Flow

Your initial instinct might be to keep to one side, as you would on a sidewalk. That’s a good start, but it’s insufficient. The flow in Tenjinbashisuji is less like a two-lane road and more like a river. It’s a single body of water with eddies, currents, and obstacles. People weave side to side, drawn to a flash sale at a drugstore or the scent of freshly baked bread. The key isn’t walking in a straight line; it’s being predictable in your unpredictability.

When crossing from one side to the other, you don’t just cut across. You communicate your intention through body language—a slight shoulder turn, a subtle pace change. You look for a gap in the oncoming crowd and merge smoothly, like a car switching lanes on a busy highway. Elderly women with shopping carts are masters of this. They move slowly but with unwavering purpose, and the crowd parts for them like the Red Sea. They are the battleships in this river; you are a canoe. Watch and learn. The goal is smooth movement without breaking anyone else’s stride. It’s a collective effort, a silent agreement to keep the system from grinding to a halt.

The Cardinal Sin: How to Stop Without Causing a Pile-Up

Eventually, something will catch your eye, making you want to stop—perhaps a mountain of glistening strawberries, a window full of cartoon-character socks, or a butcher selling hot croquettes. The absolute worst thing you can do is come to an abrupt halt in the middle of the flow. This is the shotengai equivalent of a four-car pile-up. You’ll feel a wave of frustration from those behind you, a chorus of silent sighs.

The local technique is the slow drift. Upon spotting your target, you begin to decelerate while angling your body toward the arcade’s edge. By the time you stop, you should be safely out of the main current, nestled in the storefront’s invisible harbor. This move shows respect for everyone else’s journey. It’s a physical expression of the Osakan mindset: be efficient, be practically considerate, and above all, don’t obstruct someone else’s hustle. Everyone’s busy, everyone has somewhere to be, and the shared space of the arcade works only if everyone respects the flow.

Decoding the Price Tags: It’s More Than Just Numbers

In Tokyo, shopping often feels like a calm, carefully curated experience. Prices are clearly displayed, printed in a neat, corporate font. The appeal lies in the quality, the service, and the branding. In Tenjinbashisuji, however, the value proposition is boldly shouted at you in bright red, hand-painted characters on a piece of cardboard. Shopping here isn’t a passive activity; it’s a treasure hunt, a sport, with price tags serving as your game board.

The Joy of the Bargain: Understanding “Meccha Yasui!”

The phrase you’ll hear and see everywhere is “Meccha yasui!” – meaning “Super cheap!” For an Osakan, finding a great deal isn’t just about saving a few hundred yen. It’s a victory. It’s a story to share with neighbors. It’s proof of your shopping savvy. The excitement lies in the hunt. That’s why the price tags are so dramatic. They don’t just provide information; they stir up excitement.

Look for signs written with thick black marker, prices circled in vivid red ink. Look for bundle deals: a net bag of onions, three pairs of socks taped together, two packs of tofu for the price of one. These aren’t just discounts; they’re challenges. Can you use all those onions before they spoil? Do you really need three pairs of identical socks? The shopkeeper is betting you can’t resist the perceived value. Your task is to decide if the deal actually makes sense for you. This constant mental calculation, weighing value against utility, captures the essence of Osakan consumerism. It’s a world apart from passively accepting prices in a sleek Tokyo boutique.

The Afternoon Ritual: Surviving the Time-Sale Frenzy

As the afternoon sun fades, a new energy sweeps through the arcade. This is the magic hour of the “time sale” (`taimu sēru`). Grocery stores and `sōzai-ya` (shops selling prepared side dishes) need to clear out fresh inventory before closing. So, the discounts begin.

Around 3 or 4 PM, the first stickers appear: 10% off, then 20% off. This is for the cautious—those who want to secure the exact bento box or salad they desire. But the real veterans wait. They circle the aisles, watching and waiting. By 5:30 or 6 PM, the real excitement starts. A store employee appears with a sticker gun, and a quiet crowd gathers. The coveted `han-gaku` (half-price) stickers are put on. This is the moment of truth. You must be fast and decisive, but not rude. There’s an etiquette: no snatching something from someone else’s hand. You move with purpose, claim your prize, and step aside.

This daily ritual isn’t just for those struggling financially. It’s a game of strategy and timing, enjoyed by everyone from students to well-dressed office workers. It reflects a core Osaka value: why pay full price for something you can get for half an hour later? It’s not about being cheap; it’s about being clever (`kashikoi`). It’s the ultimate expression of practicality, a daily reminder that value is something you create, not simply something you’re given.

The Soundtrack of the Shotengai: Listening for Clues

Close your eyes for a moment in the midst of the arcade. What do you hear? It’s a symphony of commerce. The squeak of bicycle brakes, the sizzle from a takoyaki stand, the tinny pop music spilling out of a pachinko parlor. But the most important sounds are the human voices. The language of Tenjinbashisuji is a performance, a continuous exchange that carries more meaning than any price tag.

The Seller’s Call: An Invitation to Engage

The vendors’ calls are the heartbeat of the arcade. They are loud, repetitive, and rich with local flavor. “Saa, yotte rasshai, mite rasshai!” (Come on, come and see!). “Kyō no o-kaidoku hin ya de!” (This is the bargain of the day!). “Okusan, kore oishii de!” (Ma’am, this is delicious!).

This isn’t the polite, almost whispered “Irasshaimase” (Welcome) you hear in a department store. It’s a direct, personal appeal. The vendors are not faceless clerks; they are distinct personalities. They aim to catch your eye and spark a conversation. The tone of their voice reveals everything. Is it a desperate end-of-day plea to clear stock? A proud announcement of fresh goods? A playful, teasing invitation? Listening to these calls is like reading the emotional stock market of the street. In Tokyo, customer service often emphasizes maintaining a respectful distance. In Osaka, it focuses on closing that gap, turning a transaction into an interaction.

The Customer’s Banter: The Art of Soft Negotiation

Though direct haggling over a 100-yen radish is rare, there is a subtle art of negotiation through conversation. It’s less about altering the price and more about cultivating a relationship that may bring future benefits. This benefit is called `omake`.

`Omake` means a little extra, a freebie. You earn it not by demanding a discount, but by showing genuine interest and being a good customer. Chat with the old man at the fruit stand. Ask him about the melons. Compliment his selection. Buy a few apples. As he bags them, he might toss in an extra, slightly bruised one with a gruff, “Kore, omake ya” (This one’s extra). This gesture is a mark of respect, a small token that strengthens your relationship. You’re no longer just another customer; you’re someone who appreciates his apples. This rarely happens in the anonymous, efficient supermarkets that dominate other cities. In Tenjinbashisuji, your personality becomes part of the transaction, and the rewards go beyond the financial.

A Practical Grocery Run: Assembling Your Tenjinbashi Pantry

Now that you know how to walk, read the signs, and listen, it’s time to actually start shopping. A grocery trip in Tenjinbashisuji isn’t a one-stop-shop experience—that’s the supermarket mindset. Here, you create your meal from a variety of specialists, each offering their own expertise and character. This is how you secure the best quality, price, and overall experience.

The Foundation: Super Tamade and the Neon Jungle

Every great journey requires a starting point, and for many Tenjinbashi shoppers, that starting point is Super Tamade. It’s impossible to miss—an explosion of loud neon lights, blinking signs, and a relentlessly cheerful store jingle that sticks in your mind for days. Tamade is an institution, emblematic of Osaka’s passion for unapologetic bargains.

This is where you pick up your staples: milk, eggs, bread, cooking oil, basic vegetables. The prices often shock with their low cost. Tamade is renowned for their 1-yen sales, where purchasing a certain amount lets you snag a single item for just a penny. These are, of course, loss leaders designed to lure you inside. The true skill of a Tamade shopper lies in navigating the store with a clear goal: buying genuine bargains and ignoring the average-quality items disguised in neon. The produce might not be the prettiest, and the meat may not be top-grade, but for everyday essentials, it’s unbeatable. Tamade embodies the Osakan philosophy of “good enough.” It’s not about luxury; it’s about sustenance. It’s about accomplishing your mission cheaply and efficiently, freeing up money for what truly matters.

The Specialists: Building Your Meal with Experts

Once you’ve gathered your basics from Tamade, it’s time to seek quality. This is where you step out of the world of packaged convenience and enter the realm of specialists. These small, often family-run shops are the heart and soul of the arcade.

The Tofu Maker (`Tōfu-ya`)

You’ll smell the `tōfu-ya` before you see it—a clean, warm, beany fragrance. Inside, blocks of freshly made tofu rest in cool water, steam rises from vats of soy milk, and the atmosphere is humid and serene. This is a far cry from supermarket plastic-wrapped tofu. Here, you have choices: the firm `momen` tofu ideal for stir-fries, the silky `kinu` tofu perfect for cold dishes like `hiyayakko`, and deep-fried pouches called `abura-age` for miso soup or stuffed with rice. The best part is the person behind the counter. They’re not just a cashier; they’re a craftsperson. Ask them, “Which tofu is best for `sukiyaki`?” and they’ll offer a thoughtful answer—they made it with their own hands, after all. You’re not merely buying a product; you’re buying their expertise.

The Fishmonger (`Sakana-ya`)

The fishmonger’s stall bursts with color and activity. Silver scales shimmer under fluorescent lights, bright red tuna is expertly sliced, and the sharp, fresh scent of the ocean fills the air. For foreigners, a traditional fishmonger can be intimidating. Don’t be. Just ask one simple question: “Kyō no o-susume wa?” (What do you recommend today?). This question changes everything. It shows respect for their knowledge and opens a conversation. They won’t try to sell you the priciest fish; they’ll offer the freshest, seasonal catch they’re proud of. They might suggest a fish you’ve never heard of and give you a quick cooking tip. Build a rapport with your local fishmonger, and you’ll eat better than you imagined. They’ll start recognizing you and might even set aside a particularly good cut of mackerel for you. This is more than shopping—it’s a relationship.

The Butcher (`Niku-ya`)

Tenjinbashi’s butcher shops are famous for more than just fresh meat. Look at the heated display at the front: golden-brown, deep-fried delights like `korokke` (potato and meat croquettes), `menchi-katsu` (minced meat cutlets), and other fried treats. These are the Osaka home cook’s secret weapon. On busy nights, you don’t have to make everything from scratch. Grill the fish from the `sakana-ya`, prepare a simple soup and rice, and add a couple of hot, crispy `korokke` from the butcher. It’s inexpensive, delicious, and a massive time saver. It epitomizes Osaka pragmatism: a shortcut to a satisfying homemade meal.

The Greengrocer (`Yao-ya`)

The greengrocer’s stall spills into the arcade—a chaotic mound of seasonal produce. Unlike supermarkets that stock everything year-round, the `yao-ya` operates as a living calendar. In winter, you’ll find piles of `daikon` radish and `hakusai` cabbage; in spring, bamboo shoots and strawberries; and in summer, glossy eggplants and cucumbers. Prices are written on cardboard signs, and the best bargains are for whatever is most abundant. Shopping at the `yao-ya` teaches you to cook and eat seasonally. It forces creativity. You might not have planned to buy a whole cabbage, but it’s incredibly cheap today, prompting thoughts of `okonomiyaki` or hot pot. This is how Osakans shop: not with a rigid list, but with an open mind, responding to the market’s daily opportunities.

Eating on Your Feet: The Tenjinbashi Fueling Strategy

Shopping in Tenjinbashisuji is more like a marathon than a sprint—you’ll need sustenance. The arcade is renowned for the concept of `kui-daore`, commonly translated as “eat until you drop.” However, here it’s not about indulgent, costly meals, but rather a steady flow of affordable, tasty, and convenient snacks that are deeply woven into the street’s commercial culture.

Putting “Kui-daore” into Practice

The street food of Tenjinbashi isn’t aimed at tourists; it’s for locals. It’s the shopkeeper’s lunch break, the after-school treat for kids, the quick dinner for commuters. The `korokke` from the butcher shop perfectly illustrates this. For under 100 yen, you get a hot, savory, and satisfying snack that can be enjoyed while walking. Takoyaki stands are everywhere, and watching the vendors skillfully flip the batter balls at impressive speed is a show in itself. These are no fancy dishes—they are calories delivered with maximum efficiency and flavor, the fuel that keeps the arcade alive. Eating on your feet in Tenjinbashi means joining in its rhythm and understanding that in Osaka, food is primarily about energy and enjoyment, not presentation.

The Sanctity of the Kissaten

When you need a genuine break, you don’t head to a sleek, minimalist café. Instead, you step into a `kissaten`. These traditional coffee shops are like time capsules. The lighting is soft, the chairs upholstered in plush velvet, and the air may carry a faint hint of stale cigarette smoke (though many are now smoke-free). Here, time seems to slow. You might see an elderly man carefully reading a newspaper, a group of women chatting for hours over one cup of coffee, or two businessmen quietly sealing a deal in a corner booth.

A `kissaten` in Tenjinbashi isn’t about grabbing a quick latte to go; it’s a neighborhood living room. Coffee is often brewed with a siphon, a slow, deliberate process that contrasts sharply with the arcade’s hectic energy outside. These spots are sanctuaries, essential to the community, serving a social purpose as important as the coffee they serve. They embody another side of Osaka—a need for quiet spaces to nurture relationships and conduct business away from the marketplace’s commotion.

What Tenjinbashisuji Teaches You About Osaka

After spending a few hours or even a few weeks living the Tenjinbashi life, you begin to grasp the bigger picture. This 2.6-kilometer stretch of commerce perfectly encapsulates Osaka itself. Its values, history, and character are all reflected in the way people walk, talk, shop, and eat here.

A City of Merchants, Not Warriors

Tokyo’s identity was shaped around Edo Castle. It was a city of samurai, shogun, and bureaucracy. Its culture emphasizes hierarchy, formality, and presentation. In contrast, Osaka’s identity was shaped by its port and markets. Known as the `tenka no daidokoro` (the nation’s kitchen), it was a city of merchants, artisans, and deal-makers. Its culture reflects this as well. Tenjinbashisuji is the ultimate embodiment of this merchant spirit. It’s lively, practical, somewhat chaotic, and focused relentlessly on closing deals. There’s no pretension here. Things are what they are. A radish is a radish. A good price is a good price. The relationship between buyer and seller is straightforward and human. This fundamental difference can be felt deep down. Tokyo presents itself; Osaka transacts.

The Misunderstanding of Being “Kechi”

People from other parts of Japan, especially Tokyo, sometimes describe Osakans as `kechi`, or stingy. This is a significant misconception. Walking through Tenjinbashi, it becomes clear it isn’t about stinginess. It’s about being `kashikoi`—smart, clever, and shrewd. It’s about respecting money and the hard work behind earning it. Spending too much on overpriced goods is seen as foolish. Finding great value—like a half-price sashimi platter or a perfectly good bag of onions for a few coins—is a source of pride. It’s a skill to be honed. Tenjinbashisuji is the grand university of value, and its shoppers are lifelong students. This mindset is about maximizing life’s pleasures by being wise with resources, not by denying oneself enjoyment.

Finding Your Place in the Flow

So how do you, as a foreign resident, fit into this vibrant, wonderful world? It’s simpler than you might think. You don’t need perfect Japanese or to understand every nuance of the local dialect. You just need to take part. Don’t be a mere observer. Engage. Ask the butcher which `korokke` he prefers. Ask the fishmonger what’s fresh today. Laugh at the fruit vendor’s silly joke. Try the unusual pickle you’ve never seen before. Compliment the tofu maker on her skill. Let go of your rigid shopping list and embrace the day’s possibilities.

By doing this, you stop being a tourist in your own life. You become part of the flow, another character in the ongoing play of Tenjinbashisuji Shopping Street. You’ll discover that the clichés about Osaka being “friendly” aren’t clichés at all. That friendliness comes from shared participation in the daily hustle. In the quiet elegance of a Tokyo department store, you’re a guest. But in the boisterous, welcoming chaos of Tenjinbashi, you’re a neighbor. And that makes all the difference.