In the very heart of Osaka, a city pulsating with neon energy, futuristic architecture, and an insatiable appetite for the here and now, lies a profound silence. It rests within a vast, open field, a sea of green grass stretching beneath the shadows of modern skyscrapers and the watchful gaze of the iconic Osaka Castle. This is Naniwa Palace Site Park (Naniwa no Miya Ato Koen), a place that doesn’t shout for your attention but rather whispers a story of immense consequence. This is not merely a park; it is the spectral footprint of Japan’s first true capital city, an imperial center that predates both Nara and Kyoto. Here, on this unassuming patch of earth, the very concept of a unified Japanese state was forged, a grand vision modeled on the great empires of continental Asia. It is a place of phantom grandeur, where the winds carry the echoes of emperors, court officials, and foreign envoys who walked these grounds over thirteen centuries ago. To stand here is to stand at a nexus of time, where the forgotten past coexists with the vibrant present, offering a connection to the deepest roots of Japanese civilization, hidden in plain sight amidst the urban sprawl. It is a testament to what was lost, what was found, and the enduring power of a dream that shaped a nation.

For a deeper exploration of the site’s history and significance, visit our detailed guide to the Naniwa-no-Miya Palace Ruins.

The Soul of a Lost City: An Atmosphere of Imagination

The first thing that captures your attention upon entering Naniwa Palace Site Park is the vast, unspoiled space. In a metropolis as densely built-up as Osaka, this broad stretch of open land feels like a purposeful, breathtaking pause. There are no towering pagodas, no intricately carved gates, no crowds of tourists jostling for photos. Instead, there is grass, sky, and a profound sense of quiet that seems almost unimaginable this close to the city center. The atmosphere is not one of emptiness, but of presence—the tangible presence of what once existed. Your imagination becomes the primary guide here. As you walk across the carefully maintained lawns, you are stepping on layers of history, each blade of grass a testament to the buried chronicles of an empire. The air itself feels different, heavy with untold stories. The distant hum of traffic on the Hanshin Expressway serves as a constant reminder of the modern world, yet it only enhances the park’s tranquility, creating a surreal bubble where time flows differently.

This is a place that invites you to slow down, to look more closely, to feel rather than just observe. You’ll notice the ground isn’t completely flat; subtle rises and raised platforms suggest the massive structures that once dominated the landscape. The most striking features are the stark, vermilion concrete cylinders representing the bases of the great pillars of the Daigokuden, the main audience hall. They stand like solemn sentinels, solitary markers of imperial power. Standing among them, the scale of the original palace start to become clear. You close your eyes and the sounds of the city fade away, replaced by the imagined rustle of silk robes, the low murmur of courtly Japanese, the rhythmic beat of ceremonial drums. You can almost see the emperor seated on his throne, receiving reports from distant provinces or greeting ambassadors from Korea and China. The park’s true beauty lies in this interactive experience—a collaboration between the archaeological remnants and the visitor’s own imagination. It offers a deeply personal and meditative journey into the past, in striking contrast to the more guided experiences found at reconstructed historical sites.

A Tale of Two Palaces: Unraveling Japan’s Imperial Dawn

To fully grasp the importance of this expansive grassy field, one must recognize that it was the site of not one, but two imperial palaces, each marking a crucial chapter in Japan’s development. The tale of the Naniwa Palace is the story of Japan’s ambitious transformation from a collection of powerful clans into a centralized, bureaucratic state, consciously modeled after the sophisticated political systems of Tang Dynasty China.

The Early Naniwa Palace: Emperor Kotoku’s Bold Vision

The origins of the first Naniwa Palace stem from a dramatic political coup in 645 AD known as the Isshi Incident, which ushered in the Taika Reforms. This revolutionary period was driven by a new generation of leaders, including Prince Naka no Oe (later Emperor Tenji) and Fujiwara no Kamatari, who aimed to wrest power from the dominant Soga clan and reshape the nation. Their goal was daring: to establish a centralized government with the emperor at its absolute core, supported by a legal code, a rationalized tax system, and a capital city befitting a rising empire. To break free from the entrenched traditions and power centers of the Asuka region in Nara, Emperor Kotoku, who ascended the throne in 646, made a bold move. He relocated the capital to the strategic coastal plains of Naniwa, at the mouth of the Yodo River.

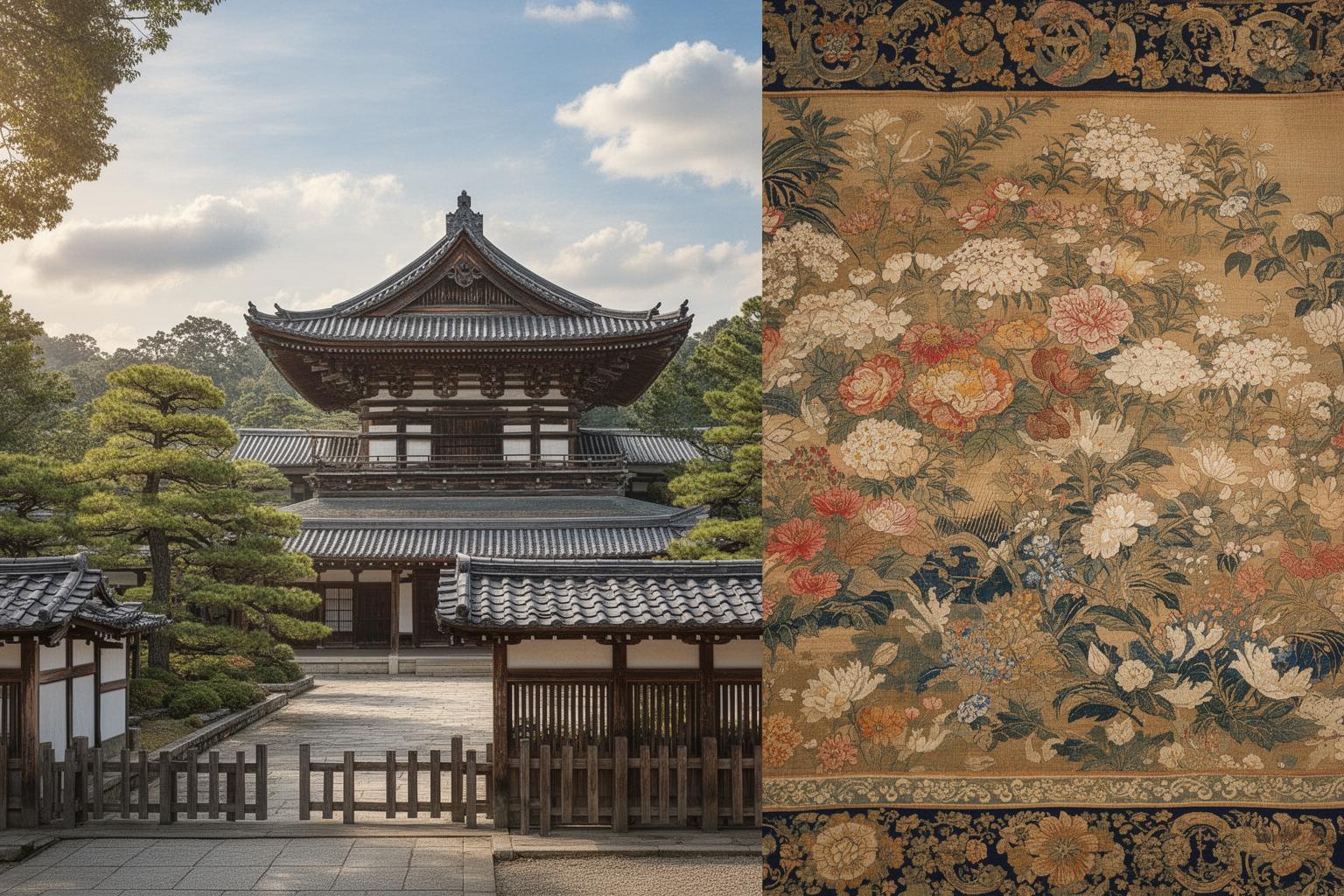

This choice was deliberate. Naniwa had long served as Japan’s gateway to the world, a bustling port linking the archipelago to the advanced cultures of the Korean peninsula and mainland China. By establishing his court there, Emperor Kotoku was signaling an outward-looking stance: Japan was prepared to engage with and learn from its powerful neighbors. Building the Naniwa Nagara-Toyosaki Palace was a monumental project. For the first time in Japanese history, a city was laid out on a grid system, directly influenced by Chinese urban planning principles. At its center was the palace complex, a vast compound of immense wooden buildings with sweeping tiled roofs, vivid vermilion columns, and intricate ornamentation. The centerpiece was the Daigokuden, the Great Hall of State, Japan’s first true imperial throne room. Here, the emperor conducted state affairs, promulgated laws, and received foreign dignitaries, projecting an unprecedented image of power and authority. Yet this golden age was fleeting. Political intrigue, resistance from conservative factions, and the emperor’s declining health led to the court’s return to Asuka in 654. Emperor Kotoku died a year later, heartbroken, in his grand but deserted capital. The first Naniwa Palace, a symbol of radical change, was abandoned and eventually dismantled, its grand vision seemingly lost amid shifting political tides.

The Later Naniwa Palace: Rising From the Ashes

For decades, the site remained silent, a testament to a broken dream. Yet the strategic value of Naniwa’s port never diminished. As Japan entered the Nara Period in the 8th century—a time of immense cultural flowering and imperial consolidation—the need for a secondary capital and a secure port became clear. Emperor Shomu, a devout Buddhist and one of Japan’s most powerful rulers, once again turned to the plains of Osaka. In 726, he commissioned the rebuilding of the Naniwa Palace, not as the main capital, but as an important Fukuto, or secondary imperial residence and administrative center.

This was no simple renovation; the Later Naniwa Palace was constructed on an even grander scale than its predecessor, reflecting the wealth and confidence of the Nara court. Archaeological excavations reveal a more refined layout, sturdier buildings, and a more majestic overall design. The palace served as a critical logistical hub, a diplomatic gateway where foreign missions were received before proceeding to the main capital at Heijo-kyo (Nara), and a favored retreat for the emperor. Emperor Shomu himself spent considerable time here, managing the affairs of a state deeply engaged in international trade and cultural exchange. However, fate again dealt a harsh blow to the palace by the sea. After the capital permanently moved to Heian-kyo (Kyoto) in 794, Naniwa’s role as an imperial center declined. The final catastrophe occurred in 793, when a devastating fire, likely sparked by lightning, consumed the magnificent wooden structures. This time, the palace was never rebuilt. The charred ruins were gradually buried under layers of silt and sand brought by the flooding Yodo River. For over a thousand years, Japan’s first great imperial capital disappeared from view and, for many, from memory—becoming the stuff of legend preserved only in ancient chronicles like the Nihon Shoki.

The Great Rediscovery: Archaeology Meets Urban Legend

The story of Naniwa Palace’s rediscovery is as compelling as its history. For centuries, its exact location remained a mystery, sparking scholarly debate and local legends. Although ancient texts confirmed its existence, physical evidence had vanished, buried beneath the earth and concealed by Osaka’s relentless urban expansion. The quest to find the lost capital became a lifelong passion for many, none more so than the committed archaeologist Tokutaro Yamane. Motivated by strong conviction and guided by historical maps and literary clues, Yamane spent years surveying the region, firmly believing the legendary palace was hidden beneath the city’s southern Chuo Ward.

His determination faced skepticism until 1953, when fate stepped in. During the construction of a new warehouse, workers uncovered an unusual artifact: a fragment of an ancient roof tile linked to Nara period temples and palaces. This single piece became the key to solving the mystery. Yamane hurried to the site, and his findings confirmed his theories. The discovery set off one of Japan’s most important post-war archaeological excavations. Over the subsequent decades, a team of archaeologists carefully peeled back layers of urban development. They uncovered the foundations of large structures, remnants of ceremonial courtyards, and a wealth of artifacts—pottery, coins, wooden tablets, and the distinctive roof tiles that first indicated the site’s significance.

Their findings were remarkable: the complete footprint of not one but two palaces, built one atop the other. The layout corresponded perfectly with descriptions in ancient chronicles. Osaka, which had unknowingly sat atop its imperial origins for centuries, was finally reconnected to its ancient past. A decision was made to preserve this invaluable national heritage, and the area was designated a National Historic Site. Warehouses and buildings were removed, and the land transformed into the public park we see today—a space dedicated to memory and discovery, honoring the city’s profound and long-forgotten roots.

What to See and Feel Today: A Walker’s Guide to the Past

Visiting Naniwa Palace Site Park is an engaging journey of active exploration and historical empathy. Although the grand buildings have long disappeared, the preserved foundations and carefully reconstructed elements provide a clear blueprint of the past, inviting you to piece together the imperial story.

The Daigokuden Platform: Standing Where Emperors Once Ruled

At the heart of the park stands the elevated platform marking the site of the Daigokuden, the Great Hall of State. Climbing the gentle grassy slope, you reach a broad concrete plaza dotted with large, cylindrical vermilion pedestals. These mark the precise locations where the massive wooden pillars of the hall once stood, supporting a vast roof covered in ceramic tiles. The scale is awe-inspiring. Measuring out the dimensions, you begin to appreciate the immense size of the structure. This was the ceremonial center of the empire, a space designed to evoke awe and reverence. Find the central spot where the Takamikura, or imperial throne, would have been located. Stand there and take in the full 360-degree view. To the north, the majestic keep of Osaka Castle rises above the trees, a strong symbol of feudal Japan. To the south, east, and west, the modern cityscape of Osaka stretches to the horizon. From this vantage point, you are literally standing at the crossroads of Japan’s ancient, feudal, and modern periods. It is a deeply moving experience, a moment to reflect on the vast sweep of history unfolding before you.

The Inner Palace and Chodoin Cloisters: Following Imperial Footsteps

Heading south from the Daigokuden platform, you enter the Chodoin area, a complex of administrative buildings where the state’s bureaucracy once operated. Here, stone outlines and gravel paths mark the layout on the grass, allowing you to trace the corridors and enter the courtyards of these formerly bustling government offices. This is where ministers convened, scribes recorded imperial edicts, and the daily workings of a centralized government took place. Walking these paths feels like following the footsteps of ghosts. You can envision the ordered, symmetrical beauty of the complex, with its covered walkways connecting various halls. The rigid north-south axis and perfect symmetry physically embodied the Confucian ideals of order and hierarchy that the Taika Reforms sought to establish. Further along, you find the foundations of the Dairi, the emperor’s private living quarters, a more secluded part of the palace. Exploring these outlines helps distinguish the palace’s public, ceremonial functions from the private, daily life of the imperial family.

The Osaka Museum of History: Bringing the Palace to Life

While the park offers the authentic physical setting, the nearby Osaka Museum of History provides crucial context and vivid detail. A visit to the park feels incomplete without stopping at this excellent museum. The two experiences complement each other perfectly. After exploring the grounds and engaging your imagination, head to the museum located just across the road from the park’s northeast corner. The upper floors focus entirely on the Naniwa Palace era. Riding up in the elevator feels like a symbolic journey back in time. On the 10th floor, a stunning full-scale reconstruction of a section of the Daigokuden’s interior awaits, complete with life-sized mannequins of court officials dressed in colorful period attire. Seeing the vibrant pillars, the intricate ceiling details, and the imposing throne up close brings the palace to life in a way the outdoor foundations cannot. The museum also exhibits a vast collection of artifacts unearthed from the site—pottery used in daily life, elegant roof tiles that once adorned the buildings, and wooden slips used for record-keeping. Detailed scale models illustrate the entire palace complex as it once stood, helping you visualize the grandeur you experienced on the ground. Perhaps most strikingly, the museum’s large windows offer a spectacular panoramic view looking directly down onto Naniwa Palace Site Park, allowing you to see the entire layout from above and finally understand how all the pieces fit together.

Naniwa Palace Through the Seasons: A Tapestry of Time and Nature

The park’s atmosphere undergoes a striking transformation with the shifting seasons, presenting a fresh perspective and evoking different emotions with each visit. Its expansive open areas respond keenly to the natural world’s cycles, creating a harmonious blend of history and nature.

Spring’s Fleeting Beauty: Plum and Cherry Blossoms

Spring makes an early appearance at Naniwa Palace Site Park, marked by the blooming plum grove on the western edge. From late February to early March, these trees burst into a vivid display of pink and white flowers, their sweet scent filling the air. This tranquil spot is a favorite among locals, offering a peaceful, reflective alternative to the city’s more popular and crowded cherry blossom sites. A few weeks later, the cherry trees scattered throughout the park join in. Their delicate, pale pink petals stand out beautifully against the vermilion pillar bases and fresh green grass. To witness the remnants of Japan’s ancient capital framed by its iconic flower is to experience a scene of exquisite, fleeting beauty—a poignant symbol of the palace’s own transient glory.

Summer’s Verdant Expanse: A Green Oasis

During summer, the park transforms into a lush, vibrant sea of green. The grass grows thick and inviting under the strong sun, while broad-leafed trees provide refreshing pools of shade. The park’s vast openness offers a sense of liberation and ease, particularly cherished during Osaka’s hot, humid summer. It becomes a playground for local children, a picnic spot, and a place for quiet walks during early mornings or late afternoons when the light is golden and the heat has softened. The cicadas contribute a persistent, buzzing soundtrack—an iconic summer sound in Japan—adding another sensory dimension to the park’s historical ambiance. This is when the park feels most alive, not with past ghosts but with the simple pleasures of the present.

Autumn’s Golden Hues: Ginkgo and Crisp Air

As the oppressive summer humidity yields to autumn’s crisp, clear air, the park adopts a more subdued and reflective beauty. Ginkgo and other deciduous trees turn brilliant shades of yellow and gold, painting a warm palette against the blue autumn sky. The sun’s lower angle casts long, dramatic shadows across the grounds, highlighting the contours of the Daigokuden platform and the faint remains of buried foundations. This season is arguably the best for photography and leisurely, meditative walks. The comfortable weather and poignant colors of the changing leaves invite deeper exploration of the site’s history, the gentle melancholy of autumn resonating with the story of the lost capital.

Winter’s Quiet Contemplation: The Stark Beauty of History

Winter strips the park to its bare essence. Trees stand skeletal, grass lies dormant, and the air turns cold and crisp. In this austere season, the park’s historical foundations become more visible than ever. With no foliage to distract the eye, attention shifts entirely to the ground beneath and the stones that outline the past. A profound silence envelops the park in winter, broken only by a crow’s call or the distant murmur of the city. It is a season for solitude and deep reflection, offering a chance to connect with the site’s spirit in its most elemental form. On a clear winter day, with the low sun glinting on frost, the park holds a quiet, severe beauty that is uniquely moving.

Practical Guidance for the Modern Explorer

Navigating your way to this ancient site is incredibly easy, thanks to Osaka’s excellent public transportation system. Its central location makes the park a convenient and enriching addition to any Osaka itinerary, especially for those interested in history beyond samurai and castles.

Getting There: Your Gateway to the 7th Century

The easiest way to reach Naniwa Palace Site Park is by subway. The closest station is Tanimachi 4-chome, served by two major lines: the purple Tanimachi Line (T23) and the green Chuo Line (C18). This ensures easy access from key hubs like Umeda, Tennoji, and Namba. From Tanimachi 4-chome Station, take Exit 9. When you come up to street level, you’ll find yourself right next to the Osaka Museum of History. The expansive park is clearly visible immediately behind the museum. The main entrance to the Daigokuden platform area is just a two-minute walk from the station exit. The park’s strategic location also makes it easy to combine with a visit to Osaka Castle, a pleasant 15-minute walk to the north. Many visitors explore the ancient palace site in the morning and then head to the famous castle in the afternoon, creating a chronological journey through Osaka’s history of power.

Planning Your Visit: Tips for a Seamless Journey

- Timing is Everything: The park is a public space open 24 hours a day with no admission fee, offering great flexibility. An early morning visit lets you enjoy the site in peaceful solitude, while a dusk visit provides beautiful sunset views over the city. A typical walk through the main areas takes about an hour, but to fully appreciate the site, plan at least two to three hours to include a thorough visit to the Osaka Museum of History.

- The Perfect Itinerary: For the best experience, start with the park and then visit the museum. Walking the grounds first sparks your imagination, helping you ponder the mysteries and scale of the site. Afterwards, the museum offers a grand reveal, answering questions and filling in gaps with reconstructions, models, and artifacts. This sequence creates a far more powerful and memorable connection to the history.

- Comfort is Key: You will do a lot of walking, as the site is quite large. Wear comfortable shoes. There is little shade on the main Daigokuden platform, so on sunny days, bring a hat, sunglasses, and sunscreen. In summer, carrying a bottle of water is also advisable.

- Amenities: While the park itself is a simple open space, public restrooms are available. For food and drinks, plenty of convenience stores and vending machines are located around Tanimachi 4-chome Station and the main roads bordering the park. The museum also features a cafe and restaurant with excellent views.

- A Note for First-Time Visitors: The most important advice is to manage your expectations. Don’t expect a fully reconstructed palace like those in Kyoto. The charm of Naniwa Palace Site Park lies in its subtlety and its invitation to imaginative engagement. It is not a passive viewing experience. Come with an open mind, a curiosity for deep history, and a readiness to let the quiet landscape speak to you. The reward is a far more profound and personal understanding of Japan’s origins than any polished reconstruction could offer.

The Enduring Legacy: Why Naniwa Palace Still Matters

In a nation abundant with magnificent castles, tranquil temples, and carefully preserved historic districts, a vast empty field might initially seem unimpressive. However, the significance of the Naniwa Palace site cannot be overstated. It was more than a mere collection of buildings; it was the tangible embodiment of a groundbreaking concept. This was the crucible in which the modern Japanese state was forged. The principles of centralized authority, bureaucratic governance, and international diplomacy first practiced here would go on to influence Japanese history for the next thousand years. The palace’s design, an ambitious and direct imitation of Tang China, reflects an era of remarkable openness and a thirst for knowledge—a spirit of internationalism that has always been central to Osaka’s identity as a port city.

Standing on the Daigokuden platform today, you are connected to that pivotal moment. The decision to establish a permanent, planned capital was a radical shift from the previous tradition of relocating the court with each emperor’s reign. It marked a move toward stability, permanence, and a new national awareness. Naniwa Palace is the quiet, often overlooked first chapter in the grand narrative of Japan’s imperial capitals, the essential prelude to the more famous histories of Nara and Kyoto. Its rediscovery in the 20th century powerfully reminded us that history is alive—found not only in museums and books but lying just beneath the surface of modern life. While the park functions as a vital green space for the city, more importantly, it is Osaka’s soul—a place of quiet reflection where anyone can walk the grounds of a forgotten empire and sense the enduring heartbeat of a nation’s birth.