You see them tucked away, on quiet shotengai shopping streets and down narrow side alleys, nestled between neon-drenched pachinko parlors and bustling takoyaki stands. They have names written in curling, old-fashioned katakana, with faded plastic food models of spaghetti and fruit parfaits sitting in the window. These are Osaka’s kissaten, the traditional coffee shops that feel like a portal to a different era. Step inside one before 11 a.m., order a single cup of coffee, and something magical happens. A thick slice of golden-brown toast, a perfectly boiled egg, and a small salad appear alongside it, often for no extra charge or just a handful of yen. This, my friend, is ‘Morning Service’ or simply ‘Morning’. And if you want to understand the soul of Osaka, you need to understand that this is never, ever just about a cheap breakfast. It’s a philosophy, a community ritual, and a defining feature of daily life in this city.

For a newcomer, especially from a place where coffee culture means a quick takeaway cup from a global chain, the concept can be confusing. Is it a promotion? A special offer? Why would a business give away food? The answer is woven into the very fabric of Osaka’s merchant DNA. It’s a city built on the principles of ‘shobai’ (business) and ‘akinai’ (trade), where value, relationships, and long-term loyalty trump short-term profit. The ‘Morning Service’ isn’t a gimmick; it’s a handshake, a daily greeting, a quiet affirmation that you, the customer, are part of the neighborhood’s ecosystem. It’s the engine that gets Osaka’s local communities started every single day, fueled by dark-roast coffee and an unbeatable sense of getting a good deal. Forget what you think you know about breakfast. We’re going deep into the world of the Osaka kissaten morning.

To truly immerse yourself in the local rhythm that fuels these morning rituals, consider how remote workers in Osaka master the city’s unique pace and community mindset.

What Exactly is ‘Morning Service’? More Than a Meal, It’s a Mindset

Let’s explore the beautiful simplicity of the ‘Morning Service’ transaction. You enter a kissaten, usually between its opening hours around 7 or 8 a.m. and a cutoff time near 11 a.m. You take a seat. The ‘Master’—the owner, who is almost always behind the counter—gives you a nod. You order a drink. This is the crucial part. You are purchasing the drink, typically a ‘hotto cohee’ (hot coffee) or an ‘aisu cohee’ (iced coffee), priced between 400 and 600 yen. The ‘Morning Service’ is the bonus, the delightful extra that accompanies it. You aren’t ordering breakfast; you’re ordering coffee, and breakfast comes as a reward for your patronage.

The Holy Trinity: Toast, Egg, and Coffee

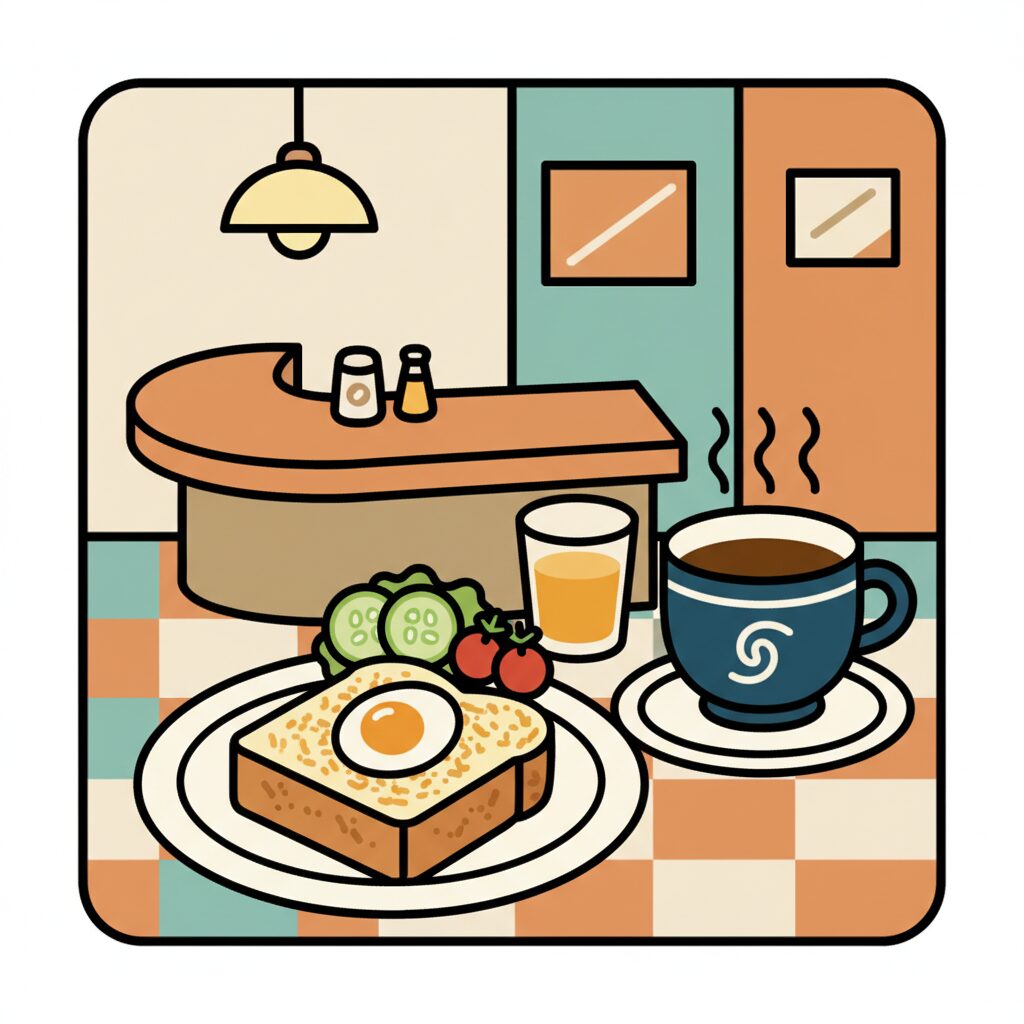

The classic, fundamental ‘Morning’ set is a lesson in satisfying simplicity. It features three core components that you will encounter, with slight variations, across Osaka.

First, the toast. This isn’t your typical thin-sliced sandwich bread. This is ‘atsugiri’ toast—a gloriously thick slice, often one and a half to two inches thick, cut from a fluffy, white ‘shokupan’ loaf. It’s toasted to a perfect golden brown, with a crisp exterior that gives way to a cloud-like, steamy interior. It arrives pre-buttered, the warm butter melting into every crevice. Occasionally, you’ll get a small packet of strawberry or orange marmalade on the side, but the buttered original reigns supreme.

Second, the egg. Most often, it’s a ‘yude tamago,’ a hard-boiled egg. It’s served warm, nestled in a small dish, sometimes with a tiny shaker of salt. The ritual of tapping it on the table, peeling off the shell, and taking that first bite of firm white and creamy yolk is a vital part of the morning rhythm. Some places might offer a small, perfectly made ‘tamagoyaki’ (rolled omelet) or a tiny scramble, but the humble boiled egg remains the iconic staple.

Third, the coffee itself. Coffee in a traditional kissaten is worlds apart from the light, acidic third-wave roasts found in trendy cafes. This is old-school Japanese coffee. Often brewed using a siphon, a beautiful, scientific-looking glass apparatus producing a clean, smooth, and incredibly aromatic cup. The beans are typically a dark roast, yielding a rich, bold coffee with low acidity and a comforting, slightly bitter finish. This is coffee designed to be sipped slowly, not downed on the run to the station.

To complete the plate, you’ll often find a small side salad. Usually simple: shredded cabbage, maybe a slice of tomato or cucumber, lightly dressed with sesame or vinaigrette. It offers a refreshing contrast to the richness of the buttered toast.

This entire set—a substantial breakfast and a quality cup of coffee—comes at the cost of coffee alone. This is the essence of ‘Morning Service.’ It’s not just a meal; it’s a statement of value. It embodies the Osaka belief that a good start to the day shouldn’t be a luxury. It’s a fundamental right, offered at a price that feels honest, fair, and smart. It’s the embodiment of ‘otoku,’ the cherished feeling of getting great value for your money, a concept Osakans hold dear to their hearts.

The Kissaten: A Living Room for the Neighborhood

To truly understand the culture of the ‘Morning Service,’ you must first appreciate the space where it takes place. An Osaka kissaten is far more than just a spot to buy coffee. It serves as a genuine ‘third place’—a refuge that is neither the high-pressure environment of the office nor the private sanctuary of home. It acts as the neighborhood’s communal living room, a stage where the subtle, quiet dramas of everyday life unfold each morning.

The moment you push open the heavy wooden door, often greeted by the small jingling bell announcing your arrival, you enter a different era. The air is saturated with the rich, comforting aroma of freshly brewed coffee, mingling with the faint sweetness of toast and, in many traditional locations, the nostalgic scent of tobacco smoke. The lighting tends to be soft and warm, emanating from ornate, vaguely European-style lamps adorned with stained-glass shades. The furniture is sturdy, dark, and crafted to endure. Picture plush, button-tufted velvet chairs in hues of burgundy or forest green, dark wood paneling on the walls, and Formica-topped tables worn smooth by decades of use.

At the center of this world is the ‘Master.’ He (and while it usually is a he, female-run kissaten, often led by a ‘Mama-san,’ certainly exist) orchestrates this morning symphony. He knows his regulars by name, remembers their usual orders without asking, and moves with a calm, practiced grace behind the counter. Whether polishing glasses, carefully preparing a siphon, or simply reading the newspaper, he remains the quiet, steady anchor of the space. The relationship with the Master builds over time, through consistent visits. It evolves from a polite nod to a gentle greeting, and eventually, to shared conversations about the weather or the latest Hanshin Tigers game. For many elderly residents living alone, this daily interaction is a crucial social lifeline.

The clientele reflects a cross-section of the local neighborhood. In one corner, a group of elderly men—the ‘ojisan’—laugh boisterously as they peruse the sports pages of newspapers provided by the shop. In another booth, a pair of ‘obachan’ (aunties) gossip over coffee and toast. A solitary salaryman might quietly prepare for his day, engrossed in documents. A student could be studying silently in a secluded corner. This is not a place for laptops or loud business calls. The dominant sounds are the clinking of ceramic cups against saucers, the soft rustle of turning newspaper pages, and the low murmur of conversations. It is a place for analog connection, for being fully present in a shared space. The kissaten serves as an informal hub of information, where people catch up on local news, check in on each other, and strengthen community bonds. It is a deeply human institution, sharply contrasting with the impersonal, transactional nature of modern chain cafes.

Osaka vs. Tokyo: The Morning Service Divide

If you’ve spent time in Tokyo, you might wonder where this culture exists. Certainly, Tokyo has kissaten, some of which are very famous and historic. However, the ubiquity and profound cultural significance of ‘Morning Service’ are much more strongly felt in Osaka and its spiritual counterpart, Nagoya. This contrast reveals a lot about the differing mentalities of Japan’s two largest cities.

Generally speaking, Tokyo’s cafe scene is often shaped by trends, aesthetics, and efficiency. There are sleek, minimalist third-wave coffee shops focusing on the tasting notes of single-origin beans. There are stylish, Instagram-ready cafes designed for photo opportunities. And there are ultra-efficient chain stores made to get commuters in and out swiftly. Breakfast is often a separate, pricier menu item; a coffee and pastry can easily cost over 1000 yen. The transaction tends to be straightforward, quick, and often impersonal.

In contrast, Osaka operates on a different wavelength. Its history as Japan’s merchant capital has deeply instilled a strong appreciation for ‘cosupa,’ or cost performance. It’s not about paying less, but about being wise with your money. Osakans derive genuine satisfaction from a deal offering great value. ‘Morning Service’ epitomizes this ‘cosupa’ mentality. Why spend 1000 yen on coffee and a croissant in a trendy Tokyo cafe when you can enjoy a full, satisfying breakfast alongside your coffee for 500 yen in Osaka? To an Osakan, the answer is clear—it’s simply good business sense.

This perspective is often misinterpreted by outsiders as stinginess or money-obsession. But that view is superficial. It reflects a practical, no-nonsense approach to life. Osakans care less about superficial style and more about authenticity and substance. A kissaten might feature worn velvet seats and dated décor, yet if the coffee is good, the toast substantial, and the Master welcoming, it’s regarded as a treasure. The value lies not in sleek design but in the quality of the experience and fair pricing. This pragmatic attitude is a hallmark of the Osaka spirit.

Additionally, the social role of the kissaten is more pronounced in Osaka’s neighborhoods. Tokyo is a city of transient residents, with long commutes and weaker community ties. Although Osaka is also vast, it often feels like a collection of close-knit villages. The local kissaten acts as a community anchor. The ‘Morning Service’ isn’t merely a customer draw; it’s a way to sustain the community by providing a reliable, affordable, and welcoming space for daily gatherings. This business model is relationship-driven rather than trend-driven—quintessentially Osaka.

Reading the Air: Unspoken Rules of the Kissaten

Entering a Showa-era kissaten for the first time can feel somewhat intimidating. It’s a well-established space with its own rhythms and unspoken rules. However, once you grasp the etiquette, navigating it becomes straightforward. This isn’t a place demanding formality, but it does value a certain respect for its ambiance.

First, ordering. Don’t wait for a menu to be brought to you. Often, it’s on the table, or you can simply ask the Master. The ‘Morning’ set is usually a standard offering, so just ordering your drink—‘Hotto cohee, kudasai’—is often enough to receive the full service. If there are options (e.g., jam or butter, boiled egg or scrambled), the Master will ask. The key is to be clear and simple. This isn’t the place for a complicated, multi-adjective coffee order.

Second, seating. Unless the place is crowded, you can generally choose your own seat. Regulars, however, often have their unspoken ‘assigned’ spots. If you notice a solitary ‘ojisan’ always sitting at the same counter stool by the window, that’s his place. It’s a small courtesy to be aware of these patterns as you become a regular yourself.

Third, duration of stay. The pace of a kissaten is unhurried. You are encouraged to linger. Unlike busy chain cafes where table turnover is crucial, here it’s perfectly acceptable to sit with your coffee for an hour or more, reading the newspaper or simply watching the world go by. Purchasing your coffee grants you the right to use that space for a reasonable period. However, during a busy lunch rush, it’s polite to be mindful and free up your seat once finished.

Fourth, the newspaper stack. You’ll almost always find a rack or pile of the day’s newspapers. These are for everyone. Feel free to take one to your table. The unspoken rule is to fold it neatly when you’re done and return it to the pile for the next person. It’s a shared resource and a cornerstone of the kissaten’s communal library.

Fifth, smoking. This is a significant point for many foreigners. Many, if not most, traditional kissaten still permit smoking. For decades they served as refuges for smokers. Although Japan’s smoking laws have become stricter, many small, owner-operated places are exempt. If cigarette smoke bothers you, be prepared for this reality. Look for a ‘kin-en’ (no smoking) sign on the door if you want to avoid smoke, but know this means missing out on some of the most classic, atmospheric spots. For many, the scent of tobacco is as much a part of the kissaten experience as the coffee itself.

Finally, paying. You almost never pay at the table. When you’re ready to leave, you take the check (if left on your table) or simply approach the cash register near the entrance. This is where you have your final brief interaction with the Master. A simple ‘Gochisousama deshita’ (‘Thank you for the meal’) is the customary, polite way to end your visit. These small rituals are the threads that weave you into the fabric of the place, transforming you from a one-time customer into a welcomed presence.

The Economics of a 400-Yen Breakfast: How Can They Do It?

The numbers just don’t seem to add up: a cup of coffee, a thick slice of toast, a whole egg, and a salad—all for the price of the coffee alone. How can a small, independent business survive, let alone thrive, on such razor-thin margins? The answer lies in Osaka’s unique business philosophy, which values long-term customer relationships and lifetime value over immediate profit.

The ‘Morning Service’ is, in modern business terms, a classic ‘loss leader.’ The profit from a single 450-yen ‘Morning’ set is minimal, perhaps even negative once rent, utilities, and the Master’s time are considered. The aim of the ‘Morning’ is not to generate money at breakfast but to bring customers through the door. It’s an investment in a future relationship. The Master is banking on offering incredible morning value so that customers will remember his shop. They might return for lunch, where a profitable ‘teishoku’ set meal is served; they might stop by for coffee and cake in the afternoon; or buy a bag of house-roasted coffee beans to take home. Most importantly, they might become regulars, coming in every single day for their ‘Morning.’

This is where the model becomes clear. A customer who visits five days a week, 50 weeks a year, is worth far more than a one-time visitor, even if the profit per visit is small. It’s a business built on volume and, more importantly, habit. The kissaten becomes an essential part of its regulars’ daily routines. While acquiring a new customer is costly, retaining an existing one is inexpensive. The ‘Morning Service’ is the most effective retention tool imaginable, cultivating a loyal clientele that sustains the business through all challenges.

This strategy is deeply rooted in the history of Osaka’s merchant class, especially the renowned merchants of Senba. They built empires on trust, reputation, and the principle of ‘shoubai wa akindo,’ roughly meaning ‘business is about not getting tired of your customers.’ It’s a long-term mindset. Rather than squeezing every last yen from a transaction, the focus is on nurturing mutually beneficial relationships that endure for years, even generations. The kissaten Master offering a generous ‘Morning Service’ operates on the same principle as the textile merchant who gave his best clients favorable deals. It ensures customers always feel treated fairly and generously, encouraging their continued return. It’s a beautifully simple, human-scale economic model that feels like a radical act in our era of aggressive monetization and shrinkflation.

A Symphony of Sounds and Smells: A Sensory Guide to the Kissaten Morning

Beyond logic and economics, the experience of a morning at an Osaka kissaten is, above all, a sensory one. It’s a full immersion into a world that engages every sense. Close your eyes, and you can almost reconstruct the entire scene through its sounds and scents alone.

First, the sounds. There’s the low, rhythmic grinding of coffee beans—a mechanical whir marking the start of the day. Then follows the gentle hiss and gurgle of the siphon brewer as hot water rises into the top chamber, a noise like a miniature science experiment unfolding on the counter. The Master’s movements are accompanied by soft percussion: the solid ‘thunk’ of a ceramic mug set down, the metallic ‘clink’ of a spoon against a saucer, the quiet rustle of a newspaper being folded. From the tables, the murmur of conversation is heard, punctuated by the occasional loud, hearty laugh from the corner booth’s ‘ojisan.’ There’s the crisp tear of a sugar packet, the crunch of toast, and the tap-tap-tap of a boiled egg cracked against a dish’s edge. It’s a gentle, comforting soundscape—an intimate contrast to the blaring traffic and station announcements just beyond the door.

The smells are even more evocative. The dominant note, naturally, is coffee—not a fleeting, faint aroma, but a deep, rich, pervasive scent of dark-roasted beans that seems to have seeped into the wooden walls and velvet upholstery over decades. It’s the first greeting at the door and the last trace on your clothes when you leave. Woven into that is the warm, comforting scent of toasting bread, a slightly sweet, yeast-filled fragrance speaking of simple pleasures. Then comes the subtle, savory aroma of melting butter, a rich, decadent layer. And yes, in many places, there’s the sharp, nostalgic, unmistakable smell of tobacco smoke—a ghost of a bygone era. It’s a complex perfume that instantly transports you, telling a story of countless mornings just like this one, stretching back through the years.

The sights offer a feast of textures and warm tones: the dark, polished wood of the counter; the deep, inviting red of velvet chairs; the gleam of brass fixtures and the intricate glass of siphons; the way morning sunlight filters through windows, illuminating dust motes dancing in the air. The Master’s movements are economical and precise—a study in focused calm. Bright colors from manga volumes and weekly magazines stacked on a shelf add vibrancy. Even the menu, often written in beautiful, flowing Japanese script, is itself a work of art.

This rich sensory tapestry is what makes the kissaten experience so unforgettable. It’s not merely about consuming food and drink; it’s about being enveloped in a complete atmosphere—an urban meditation, a moment of peace and grounding before the day’s chaos truly begins.

Beyond the Toast: The Evolution of Morning Service

While the ‘Toast and Egg’ set remains the undisputed favorite, the competitive drive of Osaka’s business owners has sparked a wonderful evolution and diversification of the ‘Morning Service.’ Not every kissaten adheres to the traditional offering. Exploring various neighborhoods reveals a delightful range of morning options, each reflecting the personality of the shop and its customers.

Some kissaten have broadened their bread selections. You might come across a ‘cheese toast’ morning, featuring a thick layer of melted cheese bubbling on top. A ‘cinnamon toast’ set, sprinkled with sugar and spice, is another popular variation. For those who enjoy sweets, some places serve ‘ogura toast,’ a specialty well-known in Nagoya but also loved in Osaka, with a generous spread of sweet red bean paste on buttered toast.

Other establishments have moved beyond bread altogether. In business districts catering to hungry office workers, you might find a ‘Morning Service’ that includes onigiri (rice balls) and a small bowl of miso soup instead of toast, offering a more traditionally Japanese start to the day. I’ve even seen kissaten near the fish market that serve a small bowl of udon noodles or a piece of grilled fish as their ‘Morning’ special—a hearty meal to fuel a physically demanding day.

Hot dog buns or sandwiches also frequently appear. A ‘hot dog morning’ might feature a small hot dog in a soft bun, while a ‘sandwich morning’ could present a couple of neat triangles of egg salad or ham sandwich. These variations demonstrate the flexibility of the ‘Morning Service’ concept. The core idea remains the same—order a drink, receive a meal—but the presentation is tailored to local tastes and the house’s specialties.

This variety turns the simple act of breakfast into a small adventure, encouraging exploration. You may have your favorite spot for a classic toast set, but on weekends, you might venture to a different neighborhood to try a kissaten reputed for an amazing hot cake ‘Morning.’ It reflects the playful, creative, and fiercely competitive spirit of Osaka’s small business owners. They are always seeking ways to stand out, offering something slightly different and better than the shop down the street. For Osaka residents, this friendly rivalry means an endless array of delicious, high-value breakfast choices.

Finding Your Spot: How to Choose a Kissaten

With countless kissaten scattered throughout the city, how do you discover a good one? This is when you need to abandon the tourist habit of relying on online reviews and top-ten lists. The best kissaten often have little to no online presence. They are local treasures, maintained by generations of regulars rather than fleeting internet fame. Finding your own favorite spot is a journey of observation and instinct.

First, look for signs of age and authenticity. Notice the faded, sun-bleached awnings. Look for old-fashioned, slightly quirky names, often written in elegant kanji or retro katakana. Check for a glass display case outside featuring waxy, slightly dusty plastic food models (‘shokuhin sampuru’). These are all hallmarks of a classic, long-established place. A brand-new, sleek cafe might be appealing, but it won’t provide the same depth of experience.

Second, peek inside. Does it feel lived-in? Are locals sitting around, chatting and reading newspapers? An empty kissaten during the morning rush may be a warning sign. A bustling room filled with neighborhood residents is the best kind of advertisement. Don’t worry if everyone seems to know one another. A new face is usually met with quiet curiosity.

Third, trust your instincts. Every kissaten has its own unique personality shaped by its decor, its Master, and its clientele. Some are quiet and studious, others lively and boisterous. Some feel cozy and cluttered, others spacious and grand. Walk past several, look through the windows, and pick the one that feels right to you. The aim isn’t to find the ‘best’ kissaten in Osaka; it’s to find the one that can become your kissaten.

Try spots that are a little off the beaten path. Wander down a ‘shotengai’ (local shopping arcade) away from tourist hotspots. Explore the residential streets behind major train stations. This is where you’ll find true neighborhood gems. Your first visit may feel slightly awkward, like stepping into a private club as an outsider. But buy a coffee, enjoy your ‘Morning Service,’ be polite, and return a few more times. Soon, the Master will start to recognize you. You’ll earn a nod, then a greeting. Before long, you won’t feel like an outsider—you’ll be part of the morning ritual, another thread woven into the rich tapestry of the neighborhood’s living room.

Becoming a regular at a local kissaten is one of the most rewarding ways to connect with the real everyday life of Osaka. It’s a small step that transforms you from a visitor into a participant in the city’s daily rhythm. It’s where you’ll hear authentic Osaka-ben dialect, understand local concerns and joys, and perhaps, for the first time, feel you truly belong.

It all begins with a single cup of coffee. But in Osaka, it comes with so much more: toast, an egg, and a deep sense of place. It’s a daily ritual that conveys this city better than any guidebook could. The ‘Morning Service’ is a microcosm of Osaka itself—practical, generous, community-oriented, and always offering incredible value. It’s a handshake, a welcome, and a quiet promise that here, a good day starts with a good deal and a full stomach. It’s not just breakfast; it’s a way of life.