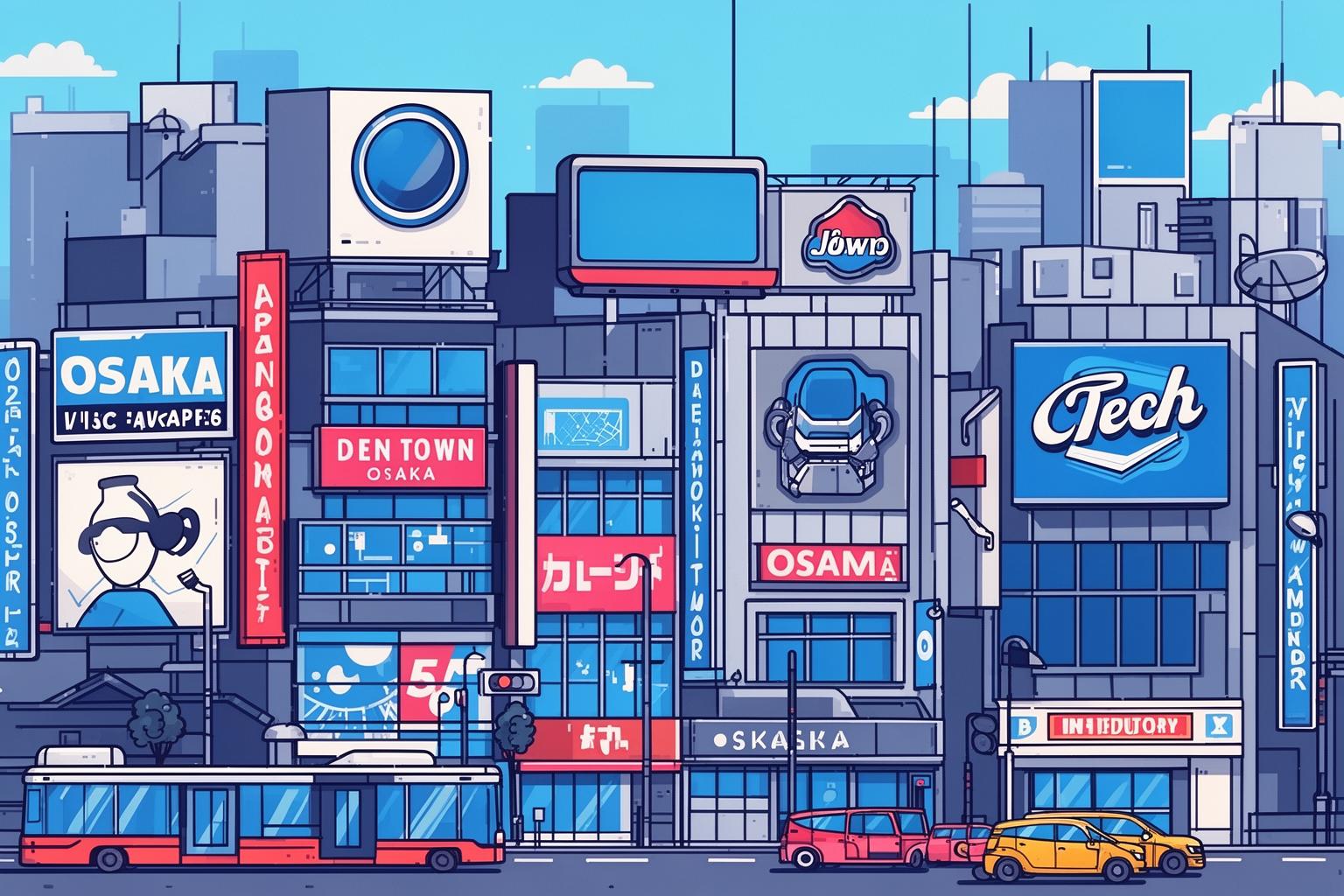

To the uninitiated, Osaka’s Nipponbashi district—affectionately nicknamed Den Den Town—presents itself as a frantic, kaleidoscopic echo of Tokyo’s Akihabara. It’s a riot of sound and colour, where towering billboards of anime heroines stare down at streets teeming with maid cafes, retro video game arcades, and shops overflowing with esoteric electronic components. A tourist might spend an afternoon here, buy a few souvenirs, and leave thinking they’ve simply visited “Akihabara, but smaller.” This is a profound, if understandable, misunderstanding. To truly grasp what makes Den Den Town tick is to look past the flashing lights and see it not as a destination, but as an ecosystem. It’s a workplace, a career ladder, a proving ground for a very specific type of Osakan ambition. The real question isn’t “What can I buy here?” but rather, “Who works here, and what does their labour tell us about the soul of this city?”

Unlike Tokyo, where corporate polish often sands down the rough edges of subculture, Den Den Town operates with a palpable, street-level hustle that is pure, unadulterated Osaka. This isn’t just a district for consumption; it’s a hub of production, repair, and relentless commerce, all underpinned by the city’s historical identity as a merchant capital. The jobs here are not mere facsimiles of those in Tokyo. They are shaped by Osaka’s distinct cultural DNA: a deep-seated pragmatism, a celebration of specialised knowledge, a direct and often brutally honest communication style, and an almost sacred devotion to the concept of kosupa—cost performance, or getting true value for your money. To work in Den Den Town is to participate in a culture where your ability to solve a customer’s problem, to demonstrate encyclopaedic knowledge of a niche product, or to drive a hard but fair bargain is valued far more than a prestigious university degree or a perfectly tailored suit. It’s a world away from the buttoned-down corporate corridors of Marunouchi. It’s a world where passion is currency and expertise is king. This article is an exploration of that world, a look beneath the surface at the unique job opportunities that exist only in this vibrant corner of Osaka, and what they reveal about the city’s enduring, iconoclastic spirit.

To further explore Osaka’s distinct local culture beyond its tech and anime hub, consider a visit to its vibrant Koreatown in Tsuruhashi.

The Retail Frontline: Where Passion is Your Payslip

In Den Den Town, retail is not seen as an entry-level, temporary job like it might be elsewhere. It is regarded as a craft. The frontline staff in these specialty shops are more than just cashiers; they serve as curators, advisors, and gatekeepers to intricate hobbies. Their value lies not in their ability to upsell but in their skill to engage customers in in-depth, fifteen-minute discussions about the subtle differences between two manufacturers of Gundam model kits. Here, Osaka’s merchant spirit merges with modern nerd culture, creating a distinct professional atmosphere.

The Figure and Merchandise Specialist

Working as a figure specialist in one of Nipponbashi’s top hobby stores is less about making sales and more about applied art history. Those who excel in this role possess knowledge nearing academic levels. They can identify the sculptor behind a limited-edition resin statue, pinpoint the exact anime episode from which a character’s pose originates, and explain why a minor paint flaw on a prize figure actually enhances its value for collectors. This knowledge isn’t from a training manual—it is gained through years of passion, countless hours on forums, and a genuine love for the medium.

This marks a key difference from the Tokyo model. In a typical Akihabara chain store, staff might be knowledgeable, but interactions tend to be transactional and efficient, following corporate protocols. Customers are expected to know what they want. In Osaka, the conversation is central to the transaction. An Osakan shopkeeper sees a hesitant customer choosing between two figures not as a hassle, but as an opportunity. They approach, not with a polished sales pitch, but with a straightforward, almost challenging question: “Docchi ga suki nan?” (Which one do you really like?). This isn’t mere small talk; it’s an invitation to dialogue. They want to understand your tastes, collection, and budget. Then they offer candid advice, weighing pros and cons like a trusted friend: “This sculpt is better, but that paint job is truer to the original art. Honestly, this one’s a better deal for the price. The other is overpriced for what it is.” That last point is crucial. An Osaka merchant prefers a smaller sale and the customer’s trust from providing genuine value over pushing the pricier item. This builds loyal clientele who return not only for products but for expert, honest counsel—rooted in Osaka’s tradition of multigenerational merchant-customer relationships.

A foreigner working in this position encounters unique challenges and opportunities. High Japanese proficiency is a must, but fluency in hobby-specific jargon is even more vital. One must know the difference between a nendoroid, a figma, and a scale figure as fluently as a native speaker. At the same time, being non-Japanese can be a considerable advantage. Many customers in Den Den Town are tourists or foreign residents, and a foreign staff member who can enthusiastically discuss Fate/Grand Order or Jujutsu Kaisen in English, Chinese, or Korean serves as a valuable bridge, making Japan’s dense hobby culture accessible worldwide. The job involves long hours on your feet, continual shelf restocking, and handling the occasional obsessive—or “otaku”—customer whose knowledge may surpass your own. But it also offers moments of pure joy: witnessing a customer’s delight when you help them find a rare item they’ve sought for years, or engaging in a deep, nerdy conversation with someone halfway around the world, connected by shared passion. This role is not just about selling plastic figures; it’s about fostering joy and curating culture.

The Retro Gaming Archaeologist

Stepping away from the shiny new releases into the dim aisles of a retro game store transports you to a different realm. Here, the job might be described as “archaeologist” or “librarian.” Staff are caretakers of digital heritage, sourcing, testing, cleaning, and pricing decades-old cartridges and consoles. It’s a meticulous, often dusty role requiring great patience and the delicate touch of a surgeon for minor repairs. The appeal of a retro game store lies not in novelty but in nostalgia and rarity.

The Osaka-Tokyo contrast is clear here. Tokyo’s retro scene, especially in Akihabara, feels highly curated and polished, with prices to match. Mint-condition, boxed items are displayed like museum artifacts, creating an intimidating atmosphere where you dare not touch. Osaka’s retro game shops, by contrast, feel more like workshops or treasure troves. Cartridges pile up in plastic bins, consoles are stacked on shelves with handwritten price tags, and the air carries the scent of old plastic and solder. This embodies Osaka’s focus on substance over style. The question asked is not “How pretty is the box?” but “Chanto ugoku n ka?” (Does it actually work?). Employees happily pull a Super Famicom from a stack, plug it into a test monitor right at the counter, and invite you to play a level of Super Metroid to confirm functionality. This openness and hands-on practicality are quintessentially Osaka.

The daily tasks for a retro game specialist involve extensive testing. A new batch of donated or purchased games arrives, each needing examination. Does the game boot? Are there graphical glitches? Does the save function work? This demands encyclopedic knowledge of old hardware and common failure points. Specialists become adept at cleaning corroded cartridge contacts, diagnosing Sega Mega Drive power issues, or spotting bootleg games by the plastic’s weight. This problem-solving, “make it work” approach reflects Osaka’s manufacturing and engineering roots.

For foreigners, this role is a deep immersion into Japanese pop culture history. It’s also a position where technical skill often surpasses language barriers. Successfully refurbishing a scratched PlayStation disc or replacing capacitors on a Game Gear gains immediate respect, even if your grammar is imperfect. Customers form a global tribe of collectors and enthusiasts. You might spend an hour explaining regional differences between Japanese and US versions of Chrono Trigger to an Australian tourist, then assist a local salaryman searching for an obscure PC Engine game from his childhood. Conversations focus less on sales and more on shared memories. The unspoken rule is that you’re not just a seller; you’re a fellow enthusiast. Admitting ignorance is acceptable, but lacking genuine passion is not. This job isn’t about climbing the corporate ladder; it’s about preserving culture and connecting people with their past, one pixelated memory at a time.

The PC Parts Guru and Custom Builder

Den Den Town also serves as Osaka’s center for PC components. Nestled among anime shops are stores packed with motherboards, graphics cards, and every imaginable type of computer hardware. The people working here are the priests of the PC Master Race, guiding newcomers through the complexities of building custom rigs. This role epitomizes Osakan pragmatism.

In Tokyo, the PC building scene can be trend-driven, focused on the latest, most powerful (and priciest) parts, RGB lighting, and achieving a specific aesthetic. Osaka’s approach starts with purpose and budget. “Nani tsukaun? Gēmu? Dōga henshū?” (What are you using it for? Gaming? Video editing?). The follow-up is always, “Yosan wa?” (What’s your budget?). The Den Den Town PC parts guru prides themselves on maximizing performance per yen. They are masters of kosupa. They’ll argue that a slightly older CPU paired with a better graphics card delivers superior gaming performance for the same price as the newest processor. They’ll recommend reliable yet unflashy power supplies over flashy, LED-laden models. Their advice is based not on marketing hype, but years of building, testing, and troubleshooting.

This builds a different type of customer bond. It’s not a one-time purchase, but ongoing consultation. Customers return months or years later for upgrade advice. “I bought this build from you two years ago. I have 30,000 yen—what’s the best upgrade to boost my Apex Legends frame rates?” The staff remembers the system, the components, and offers targeted, practical suggestions. This fosters trust that large chain stores struggle to replicate. The implicit rule is that you are allied with the customer, fighting planned obsolescence and inflated marketing claims. You are their trusted tech advisor.

Daily work involves not only advising customers but also assembling the custom PCs that keep the store running. This highly skilled technical position demands precision, deep understanding of component compatibility, and meticulous cable management. A well-built PC from a Den Den Town shop is a source of pride, showcasing the builder’s craft. For foreigners with technical aptitude, this is among the most accessible roles. Diagnosing a POST beep code or optimizing fan curves is a universal language. While customer-facing positions require strong Japanese, back-room builder roles often emphasize technical skill. The quiet satisfaction of seeing a perfectly assembled machine boot up is its own reward, embodying Osaka’s spirit of creating practical, tangible value through craftsmanship and expertise.

The Creative Core: Forging Worlds in the West

Beneath the retail facade, Den Den Town and its surrounding neighborhoods serve as a hub of creative production. This is where the games, art, and stories that fill the shelves are actually created. Osaka’s creative scene has a distinctly different character compared to Tokyo’s, often described as grittier, more independent, and less influenced by major corporate publishers. It embodies Osaka’s underdog spirit and its tradition of supporting independent artisans.

The Indie Game Developer

While Tokyo hosts giants like Square Enix and Sega, Osaka has established itself as a refuge for independent game developers. Though companies like Capcom and PlatinumGames have a significant presence, the true vitality of Osaka’s game development scene lies in smaller, scrappier studios, often founded by veterans from the larger firms seeking greater creative freedom. Working at an indie studio in Osaka offers a fundamentally different experience than working for a mega-corporation in Tokyo.

The hallmark of Osaka’s indie scene is its collaborative, almost communal atmosphere. There is a shared sense of camaraderie, with everyone striving to have their project stand out in a crowded global market. This contrasts with the more isolated and competitive environment of Tokyo’s larger studios. In Osaka, it’s common for developers from different studios to gather, exchange knowledge, and assist each other with technical challenges. Events like Bitsummit, held in nearby Kyoto, serve as focal points for this community, feeling less like corporate trade shows and more like large, supportive family reunions. The prevailing mindset is that a win for one Kansai-based indie studio benefits the entire region.

This ethos directly reflects Osaka’s historical merchant guilds, where businesses cooperated to ensure the prosperity of the whole market. Daily life in an Osaka indie studio is often chaotic and demanding. Teams are small, so everyone is expected to be versatile. A programmer may be asked to assist with quality assurance, while an artist might contribute to game design discussions. Hierarchies tend to be flat; the CEO might be coding alongside junior developers at the same desk. Communication is blunt and straightforward, with ideas judged on merit rather than the proposer’s rank. A bad idea will be called out, often with Osakan humor: “Sore, omoro nai wa.” (That’s just not fun/interesting). This bluntness is never personal; it’s a pragmatic focus on creating the best game possible with limited resources.

For foreign developers, this environment can be both liberating and challenging. The flatter structure and direct communication offer a welcome change from the rigid hierarchies typical of traditional Japanese companies. However, the expectation to juggle multiple roles and the intense “crunch” periods before deadlines can be stressful. Language skills are essential, not only for communication but also for actively participating in fast-paced brainstorming sessions where game concepts are born. Foreigners bring valuable outside perspectives on game mechanics and design but must articulate and passionately defend their ideas. It’s a high-pressure, high-reward setting where the impact of your work on the final product is clearly visible—a rare opportunity compared to the sprawling teams of major Tokyo studios.

The Doujinshi and Independent Artist

Den Den Town is more than just a marketplace for professional content; it’s the heart of Kansai’s doujinshi scene—the world of self-published comics, art books, and novels. For independent artists, this ecosystem offers a viable, though challenging, career path almost completely outside the traditional publishing industry. It exemplifies Osaka’s entrepreneurial spirit.

The primary difference between Osaka and Tokyo’s doujinshi scenes lies in scale and accessibility. Tokyo’s Comiket is a massive, commercial powerhouse that, while offering tremendous exposure, can also be impersonal and fiercely competitive. Osaka’s scene revolves around a network of smaller, more frequent events held throughout the city’s convention halls, fostering a more intimate, community-oriented atmosphere. Artists become familiar with their regular customers by name. They form circles, or sākuru, collaborating on projects, sharing event tables, and promoting one another’s work. It’s a grassroots movement built on personal connections and mutual support.

Working as a doujinshi artist is the ultimate freelance endeavor. Success depends directly on skill, work ethic, and self-marketing ability. The daily routine cycles between intense creation and direct sales. Weeks are spent hunched over a drawing tablet, racing to meet self-imposed deadlines for upcoming events. The artist functions not only as creator but also as writer, editor, graphic designer, production manager, and salesperson. They navigate local printing shops in Nipponbashi, negotiating prices on paper and print jobs—very much an Osakan interaction. Then comes the event itself: a full day standing behind a table, pitching work directly to readers, and handling cash. This offers an immediate and honest connection between creator and audience. If people like the work, they buy it; if not, they walk away.

For foreign artists living in Osaka, this path holds particular appeal. While the language of manga is universal, the ability to communicate with fans and fellow artists is crucial to building a following. Many foreign artists find a niche by introducing unique stylistic sensibilities to the scene. Authenticity is the unspoken rule. The community values artists who are passionate and actively engaged participants. Just selling your book isn’t enough; you are expected to mingle, purchase work from admired peers, and remain involved. It’s a demanding lifestyle requiring immense self-discipline, but offers a level of creative control and direct audience connection almost impossible to find in mainstream publishing. It’s the modern equivalent of the independent artisans who once set up stalls in old Osaka’s markets.

The Localization Specialist (Kansai-ben Edition)

This role is perhaps one of the most distinctively Osakan jobs within the creative tech sector. As more games and anime take place in Kansai, demand is growing for localization specialists who do more than translate Japanese—they must capture the unique flavor and nuance of the Kansai dialect, or Kansai-ben. This requires highly specialized skills that go well beyond mere fluency.

Translating standard Japanese is one thing; translating Kansai-ben is a completely different challenge. The dialect has its own vocabulary (meccha instead of totemo for “very”), unique grammatical forms, and a distinct rhythm and intonation conveying attitudes ranging from friendly and humorous to aggressive and sarcastic. A literal translation nearly always fails. The localization specialist’s task is to find culturally equivalent expressions in the target language. Should this Osakan character sound like a fast-talking New Yorker? A folksy Texan? A cheeky Londoner? These creative choices are crucial. This role demands not only perfect command of both languages but deep cultural understanding of Japan and the target culture.

This position highlights a fundamental difference between Osaka and Tokyo. Tokyo is the norm, the default. The Japanese spoken there, hyōjungo, is the standard language for national news and formal education. Kansai-ben, by contrast, often appears in media to depict specific character types: the funny sidekick, the tough gangster, the shrewd merchant. However, Osaka-based companies increasingly strive to portray the region with nuance and authenticity. They need localizers who truly understand that not everyone who says akan (the Kansai equivalent of dame, or “no good”) is a comedian. This creates a niche demand for talent concentrated in Kansai.

For foreigners, becoming a Kansai-ben localization specialist represents the pinnacle of linguistic and cultural integration. It requires years of living in the region and absorbing the language’s rhythm not just from textbooks but through everyday interactions at supermarkets, bars, and on trains. The job often involves close collaboration with original Japanese writers and voice actors to ensure translated dialogue retains intended personalities. Although a desk job, it remains deeply connected to the city’s living culture. You might spend your morning debating the best way to translate a complex piece of Osakan wordplay and your afternoon watching a manzai (Osaka-originated Japanese stand-up comedy) performance to stay sharp. This career proves that language is not merely a communication tool but a carrier of identity and that preserving this identity globally is a valuable and unique endeavor.

The Tech Infrastructure: The Unseen Engine

Behind the shining storefronts and innovative studios lies the crucial infrastructure that keeps Den Den Town running. These are the less glamorous but absolutely essential roles in logistics, repair, and technical support. They form the foundation of the district’s economy and embody the most practical, straightforward facets of the Osaka spirit.

The E-Commerce Warehouse Strategist

For every physical shop in Nipponbashi, there are multiple online stores shipping products to customers throughout Japan and beyond. At the core of this operation is the warehouse. Working in e-commerce logistics for a Den Den Town company is a lesson in efficiency and unyielding practicality. The objective is clear: deliver the right product to the right customer as quickly and cost-effectively as possible.

Here, Osaka’s historic role as “the nation’s kitchen”—the central distribution hub for rice and other goods—finds its contemporary form. The principles remain the same: efficient inventory control, streamlined workflows, and a constant focus on cost. The environment inside these warehouses contrasts sharply with the customer-facing side of the business; it revolves around speed, precision, and process improvement. While a Tokyo-based e-commerce firm might heavily invest in robotics and automation, reflecting a corporate emphasis on high-tech solutions, an Osakan company tends to rely on cleverly designed manual systems and a highly skilled human workforce, believing that adaptable, well-trained people often outperform rigid, costly machines. The priority is to devise smart, low-cost solutions to logistical challenges.

Daily tasks include receiving shipments, logging inventory, selecting items for orders, and packing them for delivery. It’s physically demanding labor measured in seconds—how long to pack a standard order, how many boxes per hour. Every move is optimized. The unwritten rule is always to consider ways to speed up and improve the process without sacrificing accuracy. Even a suggestion that cuts three seconds off the average packing time is highly valued. This continual drive for improvement, or kaizen, is a hallmark of Japanese manufacturing, but in Osaka, it carries a particularly sharp focus on cost-effectiveness.

This area of work is among the most accessible for foreigners, especially those without advanced Japanese proficiency. While safety guidelines and instructions are in Japanese, the work is often physical and process-driven. A strong work ethic, dependability, and attention to detail are the key qualifications. Though not the most glamorous role in Den Den Town, it provides a stable and vital function within the ecosystem. It offers an unfiltered glimpse into the engine room of Osaka commerce, where the city’s reputation for pragmatic, hardworking efficiency is built one carefully packed box at a time.

The Repair Technician and Modder

In an era of disposable electronics, the repair shop stands as a stronghold of sustainability and technical mastery. Den Den Town is sprinkled with small workshops where skilled technicians revive dead laptops, cracked smartphones, and malfunctioning game consoles. This profession directly reflects the Osakan ethic of mottainai—a sense of regret over waste—and a deep respect for extracting full value from a product.

The contrast with Tokyo is philosophical. In Tokyo, the culture often leans toward the new. When a device breaks, the instinct is typically to replace it with the latest model. The major electronic retailers in Akihabara focus on selling new products rather than repairing old ones. In Osaka, a strong countercurrent exists. The question is, “Naoseru?” (Can it be fixed?). People bring ten-year-old video game consoles to technicians hoping for resurrection. There is pride in maintaining old technology well beyond its intended lifespan.

This extends beyond repairs into the realm of modding—altering hardware to enhance its capabilities. This might include installing a new screen in a classic Game Boy, upgrading the hard drive in a PlayStation 2, or performing a region-free modification on a console. It is a highly skilled craft demanding deep electronic knowledge, steady hands for soldering, and a creative problem-solving approach. The technicians are respected in the community for their expertise. “If your WonderSwan screen is failing, you must see Tanaka-san. He’s the only one who can fix it.”

Daily life for a repair technician is a series of puzzles. Each broken device presents a new mystery to solve. The work is meticulous, requiring intense concentration and a vast mental catalog of circuit layouts and typical failures. Satisfaction comes with the moment a seemingly dead device powers on again. For the modder, there’s also the creative excitement of making something better than it was before. The workspace is often a controlled chaos of tools, spare parts, and half-disassembled gadgets—orderly only to the technician. This job suits detail-oriented foreigners passionate about tinkering. Like custom PC builders, technical skill is their primary language. Successfully micro-soldering a broken motherboard connection wins peer respect and customer gratitude regardless of Japanese fluency. This profession exemplifies Osakan values of thrift, practicality, and the quiet gratification of restoring the broken.

Ultimately, Den Den Town is far more than just a collection of shops. It is a complex, living organism—a microcosm of Osaka itself. The roles within this district, from frontline retail curators to behind-the-scenes repair experts, are all shaped by the city’s distinct cultural heritage. These are positions that reward deep expertise over surface polish, practical skills over formal credentials, and community-driven hustle over corporate anonymity. Working here means embracing a direct, no-nonsense approach to commerce and creativity. It means valuing long-term customer relationships over quick sales. It means appreciating the underdog spirit of the independent creator and the quiet genius of the technician who breathes new life into old machines. To understand the jobs of Den Den Town is to understand the pragmatic, passionate, and profoundly human heart of Osaka.