So you’ve made the leap. You’re in Osaka, or you’re thinking about it, and the initial thrill is slowly giving way to a more practical, pressing question: where on earth are you going to live? The internet will show you a parade of sterile, shoe-box apartments, identical units in silent concrete towers that promise privacy but often deliver a profound sense of isolation. You could rent one. It would be clean, quiet, and entirely your own. But you wouldn’t be choosing to live in Osaka to be alone, would you? You’re here for the noise, the energy, the feeling of a city that grabs you by the shoulders and talks right in your face, not with malice, but with an irrepressible need to connect. To truly live in Osaka, you need to be part of the conversation. And that conversation, more often than not, starts in the communal kitchen of a share house.

Forget what you know about share houses elsewhere. In Tokyo, they can be pragmatic arrangements of convenience, a collection of individuals orbiting each other politely. In Osaka, a share house is something else entirely. It’s a living, breathing organism. It’s a test kitchen for friendships, a crash course in communication, and a front-row seat to the beautiful, baffling, and hilarious theater of daily Osakan life. It’s less about splitting rent and more about splitting a plate of takoyaki someone decided to make at 11 PM on a Tuesday. Choosing a share house here isn’t just a housing decision; it’s a social contract. It’s an agreement to participate, to engage, and to embrace a little bit of chaos. It’s about finding your family, even if it’s a temporary one, in the heart of Japan’s most boisterous city. This is the search for a home that feels like one, in a place that’s always got something to say.

To truly immerse yourself in the city’s unique rhythm, consider starting your day with the local tradition of Osaka’s morning service.

The Search: More Than Just Four Walls and a Roof

Your journey begins online, scrolling through listings that start to blur together—photos of neat rooms, shiny kitchens, and smiling, multicultural residents. But in Osaka, the specs—square footage, proximity to the station, whether the toilet and bath are separate—tell only part of the story. The real insight lies in the subtext, conveyed through word choice and the types of photos they decide to share. You’re not just searching for a room; you’re auditioning for a role in an improvised, intimate play.

Reading Between the Lines of a Listing

A Tokyo listing might highlight its “professional and quiet environment,” emphasizing individual refrigerators, strict cleaning schedules, and rules displayed on laminated sheets. It promotes orderly, predictable co-living. By contrast, an Osaka listing uses phrases that reflect a different philosophy altogether. Look for the keywords that reveal the city’s character.

When a listing mentions an “at-home atmosphere” or uses the term “atarashii kazoku” (new family), this isn’t mere marketing fluff. It’s a statement of intent. It means the landlord, or `kanrinin`, regards the house as a community rather than just a property. It suggests that spontaneous living room gatherings aren’t just possible—they’re expected. It hints at a culture where the boundaries between your private life and the household’s collective life are fluid. The accompanying photos offer further clues. Are they sterile shots of empty rooms? Or are they candid, slightly blurry images of a Christmas party, a summer barbecue, or people gathered around a kotatsu, laughing? The latter is a hallmark of a genuine Osaka-style share house. They’re selling you a social life, with a room included.

Another key phrase is “international exchange” (`kokusai kouryuu`). In some cities, this can be a sterile, performative idea. In Osaka, it’s much more grounded and lively. It means you’ll find a mix of Japanese residents—often students or young professionals—who genuinely want to break out of their shells and tire of mainstream Japan’s reserved nature. They’re not just there to practice English; they’re there to debate which ramen shop is best, share their favorite Manzai comedy routines, and absorb the direct, open communication style that foreigners often bring. They see you as a vital ingredient to a livelier, more engaging household. So when you see this phrase, know that you’re invited not just as a tenant, but as a catalyst for social energy.

The “Interview”: Are You a Good Fit for the Family?

You’ve found a promising listing and arranged a viewing. Elsewhere, this might be a straightforward transaction: see the room, check the plumbing, ask about the deposit. But in Osaka, the viewing often feels more like a two-way interview, with you under close observation. The landlord or senior housemate will guide you through the space, but what they’re really doing is assessing you. They’re not just listening to your questions about the Wi-Fi speed; they’re observing how you respond to the atmosphere.

Do you smile when you notice the collection of mismatched mugs in the kitchen? Do you seem comfortable with a shared living room that’s clearly well-used, with stray cushions on the floor and a stack of manga on the coffee table? They’re gauging your tolerance for casual clutter and your ability to live communally. Their questions are telling—they might inquire less about your job and more about your hobbies. “Do you like to cook?” isn’t a casual question. It’s a test to see if you’re someone who might share meals. “What do you do on your days off?” helps them determine whether you’ll be a ghost who only sleeps in the room or someone likely to participate in house life.

This isn’t about judgment; it stems from a practical Osaka mindset. A harmonious share house, in their eyes, is like a well-balanced pot of `nabe` (hot pot). Every ingredient must enhance the overall flavor. If one element is off, it can spoil the entire broth. They’ve learned that someone who values absolute silence and solitude will struggle in a house that thrives on conversation and communal space—and that negativity can spread. In a real sense, they’re safeguarding the delicate ecosystem of the house. Your role in this interview is to be honest. If you’re a quiet introvert, this might not be the right place, and it’s kinder for everyone to realize that upfront. If you’re open to the experience, show curiosity, ask about the other housemates, and demonstrate interest in the people as much as the property.

The Unspoken Rules of the Osaka Communal Kitchen

The kitchen is the heart of any home, but in an Osaka share house, it becomes the central stage. It’s where alliances form, dramas unfold, and the city’s entire philosophy of life is showcased. It’s livelier, messier, and more interactive than its Tokyo counterpart. Learning how to navigate this space is essential for your survival and happiness. The rules aren’t written down; they’re conveyed through actions, gestures, and the sharing of food.

“Kore, tabete!” – The Politics of Shared Food

One of the first things you’ll notice is the constant, fluid exchange of food. This is not a system of accounting or reciprocation. It’s a language of community. The phrase “Kore, tabete!” (“Here, eat this!”) is something you’ll hear daily. A housemate returns from their hometown with a box of sweets? They won’t just leave it in the kitchen with a note; they’ll personally knock on your door and offer you one. Someone tries a new recipe and makes too much? They’ll serve you a bowl before you even ask. You leave a bag of oranges on the counter? Don’t be surprised if half are gone by morning, replaced with a chocolate bar and a thank-you note or, more often, a shout of thanks from across the living room.

For a foreigner used to more individualistic cultures, this can be puzzling. Is this my food? Do I owe them? Do I need to pay them back? The answer is a definitive no. To refuse an offer of food or insist on paying for it misses the point entirely. It’s not a transaction. It’s an act of inclusion. It’s saying, “I was thinking of you,” “You belong to this group,” and “We look out for each other.” Beneath it all lies a strong aversion to waste — of food (`mottainai`) and of social opportunity. Surplus food is a chance to connect. Not sharing it would seem, in the Osakan mindset, deeply odd and a little sad.

The right response is simple: accept with a smile and a hearty “Arigatou!” or “Itadakimasu!”. And when you can, join in. Bake cookies and leave them out. Bring back a quirky snack from a day trip. Offer a taste of what you’re cooking. There’s no need to keep mental scores. The system regulates itself, rooted in casual generosity. It’s a beautiful, delicious, and sometimes calorie-heavy social contract.

Noise, Laughter, and the Porous Walls of Privacy

Osaka is a city of sound: the summer cicadas, the clatter of trains, the energetic calls of shopkeepers in the `shotengai` arcades. This tolerance for ambient noise carries into the home. While Tokyo share houses may enforce quiet hours after 10 PM, an Osaka share house runs on a more flexible, organic rhythm. Privacy isn’t defined by silence but by the freedom to be yourself in a lively environment.

Don’t be surprised if one housemate is practicing guitar in the living room while another watches a Hanshin Tigers baseball game at stadium-level volume. Don’t be shocked if a spirited, laughing debate about instant ramen brands breaks out in the kitchen while you try to read next door. This isn’t rude; it’s living. The assumption is the house is a space where life happens—and life is not quiet.

Of course, there are limits. Blasting music at 3 AM is likely frowned upon anywhere. But overall, tolerance for noise is much higher. People don’t retreat to their rooms for silence; they use headphones. The expectation isn’t that the house will adjust to your need for quiet, but that you’ll find your own way to exist within its natural, vibrant hum. This can be a major adjustment for those who see home as a sanctuary defined by silence. In Osaka, home is a place of energy. The sounds of your housemates are comforting—a sign you are not alone. Laughter from the living room is a constant, open invitation to join in. The walls are thin, both physically and socially, and that’s intentional.

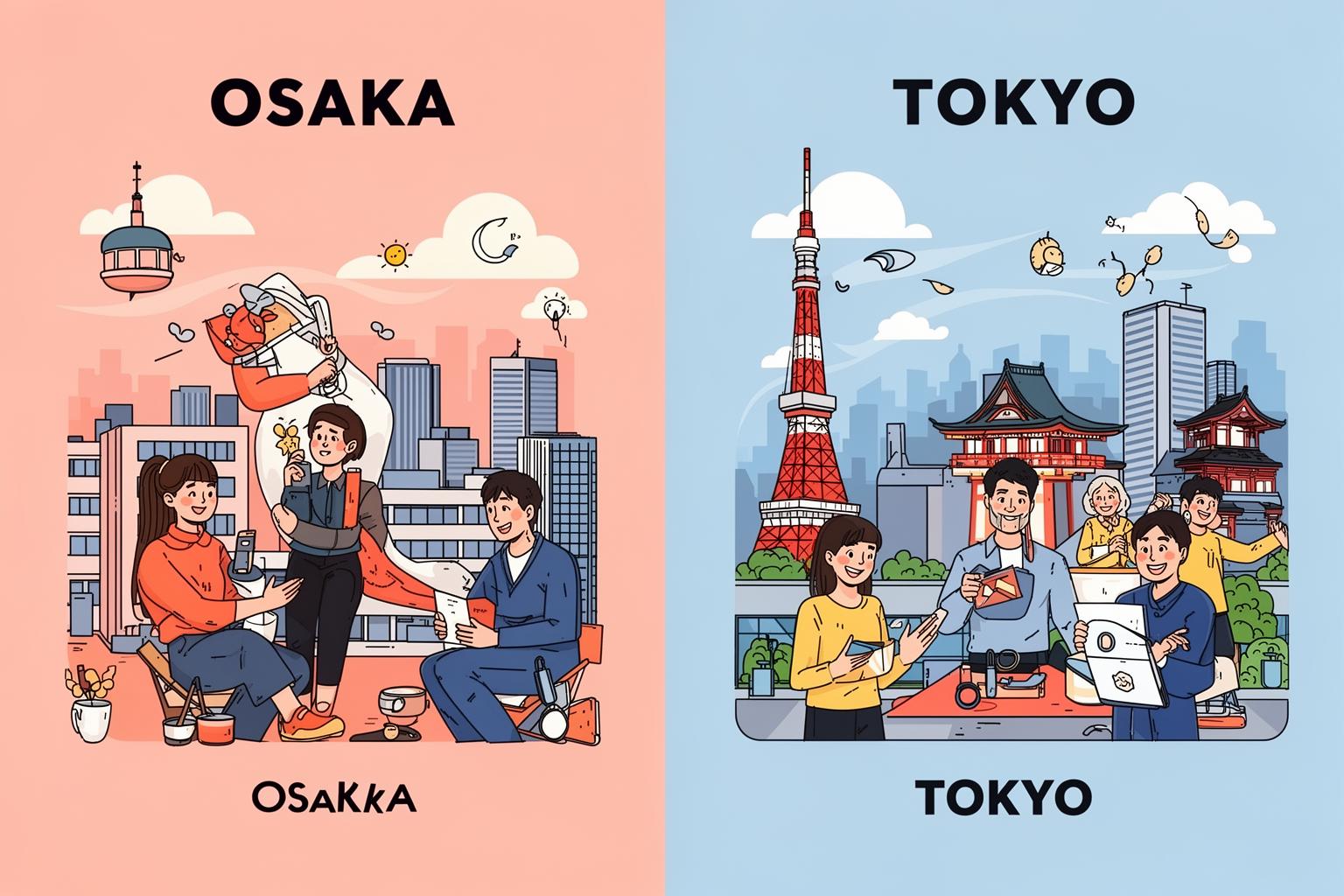

Osaka vs. Tokyo: The Share House Showdown

To fully understand the distinct character of an Osaka share house, it helps to compare it with its better-known counterpart in Tokyo. Living in a Tokyo share house versus one in Osaka is like the difference between a well-organized, efficient office and a lively, sprawling family gathering. Both have their benefits, but they fulfill fundamentally different roles and function with entirely different mindsets.

Efficiency vs. Emotion

Tokyo operates on precision, politeness, and the seamless flow of millions of people. This attitude is evident in its share houses, which are often managed by large companies with standardized contracts, professional cleaning services, and clear, top-down rules. Communication typically happens through apps or notice boards in common areas, with problems addressed efficiently and impersonally. The system is designed to minimize conflict and maximize convenience. You could live in a Tokyo share house for a year without knowing the names of your neighbors. The aim is coexistence rather than connection.

Osaka, a city shaped by merchants rather than samurai, thrives on relationships, negotiation, and genuine human emotion. An Osaka share house is usually overseen by a local landlord or a small, family-run business. Contracts tend to be more informal, and rules feel more like mutually understood guidelines than rigid regulations. The landlady (obachan) might not use an app but has your phone number and will call to check in. If you’re late on rent, it’s not an automatic penalty; instead, expect a knock on your door with a concerned, “Daijoubu? Are you okay?” This doesn’t mean chaos—social expectations can actually be stronger. You’re encouraged to build a personal connection. That same flexible landlady will also expect you to spend an hour sharing tea and listening to stories about her grandchildren. It’s a system based on mutual understanding and personal engagement. Less efficient perhaps, but infinitely more human.

The “Akan” and “Eeyan” of Daily Life

Communication styles highlight yet another sharp contrast. Tokyo’s manner, in line with general Japanese culture, is famously indirect (enryo). A recurring issue, like someone consistently leaving dirty dishes in the sink, might be addressed with a politely worded, passive-aggressive note: “Let’s all remember to keep our shared kitchen clean for everyone’s comfort.” The goal is to convey the message without causing confrontation or embarrassment.

In Osaka, this approach is seen as weak, confusing, and time-wasting. The same problem would be tackled quite differently. Instead of a note, you’d find yourself in the kitchen making toast when a housemate walks in, points at the dirty pan, and says in a half-joking, half-serious tone, “Oi, kore, akan de!” (“Hey, this is no good!”). There’s no ambiguity—direct, to the point, and over in seconds. It might come across as blunt or even harsh to outsiders, but locally it’s viewed as an honest and efficient way to handle problems. This directness shows they feel comfortable enough with you to drop formalities. They treat you like family, and families argue openly.

On the flip side, praise and approval are delivered with similar enthusiasm. Instead of a subtle nod, you’ll hear a hearty “Meccha eeyan!” (“That’s awesome!”). This emotionally expressive communication, rich in the local dialect (Osaka-ben), energizes the house. It’s a language learned not from textbooks but through participation—by listening, occasionally being called out, and learning to laugh along. It’s a style that builds bonds through honesty rather than mere politeness.

Navigating the Social Maze: Your Role in the House

Succeeding in an Osaka share house demands a mental shift. You aren’t merely renting a space; you are becoming part of a community. This comes with unspoken expectations regarding your participation and your role within the group. Staying hidden in your room isn’t a neutral action; it sends a message that is often misread as dislike or arrogance. To thrive, you need to engage.

You’re Not Just a Renter, You’re a Neighbor

In a vertical city like Tokyo, neighbors often remain anonymous faces you might only nod to in the elevator. In Osaka, especially within the horizontal, close-knit environment of a share house, being a neighbor is an active role. It begins with the basics: being present in common areas. Don’t just cook your meal and rush back to your room. Eat in the living room. Take your time over a cup of tea. If people are watching TV, join them, even if you don’t understand the program. Your presence signals your willingness to be part of the group.

Participation also includes house chores. Although there may be a cleaning rota, the spirit behind it matters more than strict adherence. If you notice the trash is full, take it out, even if it’s not your turn. If the rice cooker is empty, wash it and start a new batch. These small proactive actions are noticed and greatly appreciated. They show that you regard the house as a shared responsibility, not just a service you pay for. This embodies the Osakan merchant spirit: everyone pitches in to make the collective effort—in this case, living together—successful. You’re expected to contribute not just because rules say so, but because it’s the right thing to do.

The Art of `Tsukkomi` at the Dinner Table

One of the most challenging and rewarding aspects of socializing in an Osaka share house is mastering the local banter style. Osakan humor is famously built on the dynamic of `boke` and `tsukkomi`. The `boke` is the silly, absent-minded character who says something ridiculous. The `tsukkomi` is the sharp, witty one who points out the absurdity, often with a playful smack or a pointed verbal jab. This is the rhythm of all Manzai comedy and everyday conversation.

As a foreigner, you will often find yourself cast, intentionally or not, as the `boke`. You might mispronounce a word, misunderstand a cultural nuance, or share a naive opinion. The response won’t be polite silence; it will be an immediate and cheerful `tsukkomi`. For instance, if you say you think Tokyo-style `okonomiyaki` is quite good, you won’t hear, “Oh, that’s an interesting view.” Instead, you’ll be met with a chorus of “Nande ya nen!” (“What the heck!”) followed by a good-natured explanation of why you’re hilariously and profoundly wrong.

This can be surprising and might feel like you’re being mocked or dismissed. But it’s actually a sign of affection. It’s a form of verbal play, a way of engaging with you and drawing you into their cultural world. Being the target of a `tsukkomi` means they accept you as one of them—strong enough to take a joke and smart enough to understand it. The worst reaction is to become defensive or offended. The best is to laugh at yourself and, if you feel bold, give a `tsukkomi` back. Even if you don’t succeed perfectly, you’ll earn respect. Learning this rhythm—the playful give-and-take of teasing—is the final key to unlocking the heart of an Osaka share house. It’s how you move from being a temporary resident to, for a time, being part of the family.