Step off the train at Juso Station, and the city of Osaka transforms. Just one stop away from the glittering commercial heart of Umeda, with its soaring skyscrapers and pristine department stores, you find yourself plunged into a different era. The air here feels denser, thick with the savory steam rising from countless tiny eateries, the rumble of Hankyu trains crisscrossing on elevated tracks overhead, and the palpable energy of a neighborhood that has long served as the city’s vibrant, unpretentious crossroads. This is not the Osaka of glossy travel brochures; this is the Osaka of daily life, of after-work rituals, of culinary traditions born not in grand kitchens but on the hot steel of a communal grill. While the world knows Osaka for takoyaki and its famous cabbage-filled savory pancake, okonomiyaki, it is here in the tangled, neon-lit streets of Juso that a lesser-known but arguably more nuanced delicacy was born. We are here to talk about negiyaki, the green onion-packed pancake that represents the true soul of Osakan konamon, or flour-based cooking. It is a story of humble ingredients elevated to culinary art, a pilgrimage for food lovers seeking the authentic heart of Japan’s kitchen. To understand Osaka, you must understand its food, and to truly understand its food, you must journey to Juso, the cradle of negiyaki. Let this journey begin, into a world of sizzling teppans, aromatic soy sauce, and the sharp, sweet bite of a million finely chopped green onions.

To fully immerse yourself in the nostalgic atmosphere that defines this neighborhood, explore the enduring Showa-era soul of Juso in a dedicated feature.

The Unfiltered Vibe of Juso: A Portal to Old Osaka

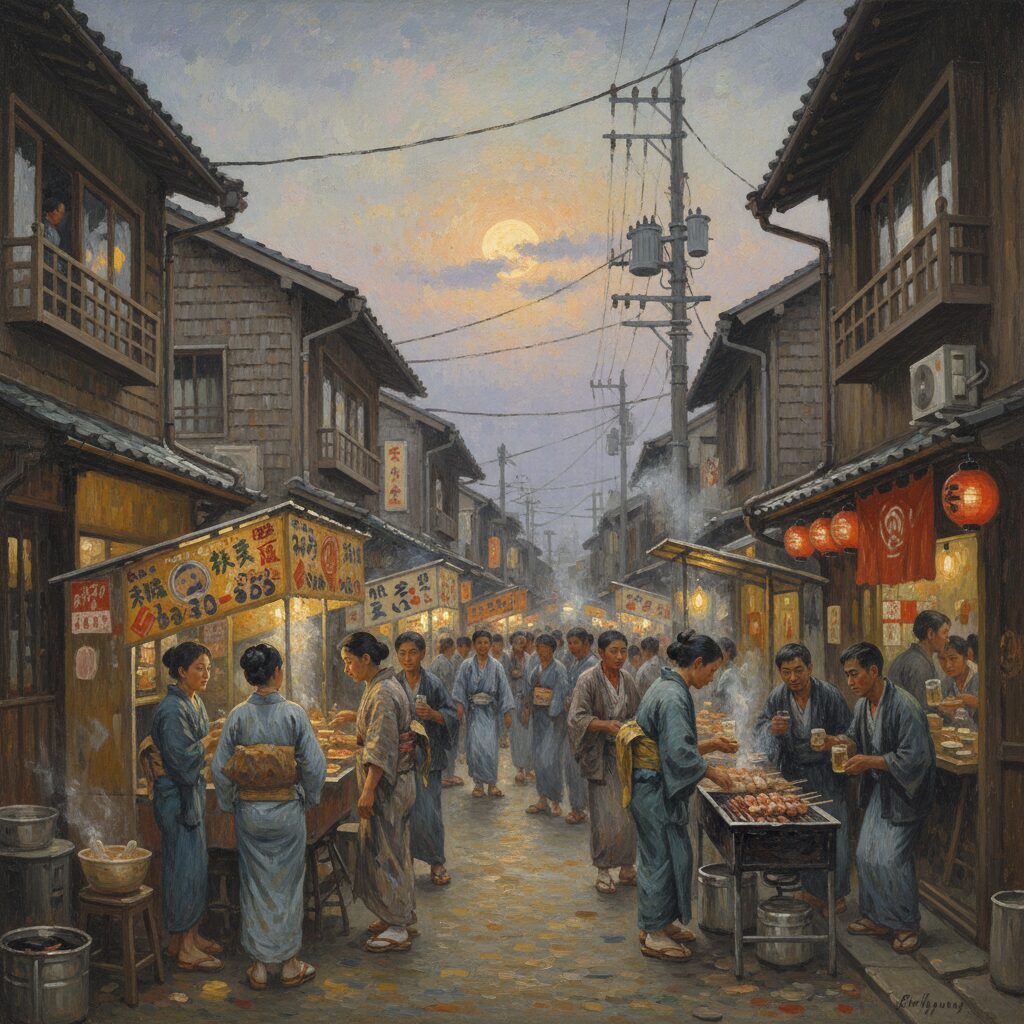

To truly appreciate Juso’s food, you first need to immerse yourself in its atmosphere. The moment you step off the station platforms, you find yourself not in just one neighborhood but in several, radiating outward like spokes on a wheel. The station serves as a grand central divider, with the west exit opening onto a slightly more modern, wider arcade, while the east side plunges you into a maze of narrower alleys, each with its own unique character. This is the raw, unfiltered essence of a Showa-era dream—a palpable nostalgia that lingers in the air. The shopping arcades, or shotengai, are far from polished tourist spots. Their tiled floors have been worn smooth by decades of footsteps, and the signs above the shops—some faded, others glowing with defiant neon—tell stories of family businesses handed down through generations. You’ll find shops selling everything from traditional Japanese sweets and pickles to discount clothing and pachinko parlors, their entrances echoing with the clatter of silver balls.

The dominant soundscape is the rhythmic clatter of Hankyu trains. Lines to Kobe, Kyoto, and Takarazuka converge and separate here, so a train is almost always rumbling overhead. This constant movement fills the neighborhood with a sense of purpose and transit—a feeling that this is a place people pass through, yet also a spot to pause, unwind, and be themselves. It’s a blue-collar heartland, where salarymen loosen their ties and friends gather over cheap beer and sizzling plates of food. Unlike the curated cool of districts like Horie or the overwhelming tourist crowds of Dotonbori, Juso feels lived-in. It has a grit and authenticity that can’t be manufactured. Walking through its covered arcades, you catch glimpses of daily life: a grandmother carefully choosing daikon radishes, a group of students laughing on their way home, the sharp, inviting aroma of grilled meat drifting from an open doorway. This is the setting in which negiyaki was born—a place of practicality, community, and an appreciation for simple, satisfying flavors.

The Genesis of a Green Delicacy: Unraveling Negiyaki’s History

The story of Osaka’s konamon culture is a captivating blend of post-war necessity and a deep-rooted passion for communal dining. While okonomiyaki—meaning ‘grilled as you like it’—became the city’s worldwide symbol with its hearty cabbage base and customizable fillings, a quieter revolution was unfolding in Juso. There, at a restaurant called Yamamoto, a new creation arose that shifted the spotlight from cabbage to another humble yet intensely flavorful ingredient: negi, the ubiquitous Japanese green onion. The birth of negiyaki was not a clever marketing ploy; rather, it was a natural evolution, responding to the tastes and preferences of the local customers. The story, as often recounted, describes a simple variation that resonated so strongly it became a new standard.

Let’s explore what distinguishes negiyaki from its more famous cousin. Whereas okonomiyaki is typically dense and filling, constructed with a mountain of cabbage and a thick, flour-based batter, negiyaki is characterized by its subtlety and emphasis on aroma. The batter is generally lighter, seasoned with savory dashi stock and soy sauce instead of a neutral base. Mixed into this batter is an almost staggering amount of finely chopped green onions, far exceeding what would be used as a simple garnish. When this mixture touches the hot teppan grill, something magical occurs. The onions don’t just cook; they wilt, sweeten, and lightly caramelize, their sharp, fresh bite mellowing into a rich, savory fragrance. The pancake itself is thinner, with a slightly crispy exterior and a tender, almost creamy interior. Rather than the thick, sweet okonomiyaki sauce and mayonnaise, the final touch is a brush of high-quality soy sauce and a generous squeeze of fresh lemon or sudachi citrus, which cuts through the richness and brightens the dish.

From a wider East Asian viewpoint, the idea of a scallion pancake isn’t unique. Similar dishes can be found in the flaky, savory cōngyóubǐng of China or the crispy pajeon of Korea. Yet what makes negiyaki distinctively Japanese, and particularly Osakan, is its preparation and signature ingredients. The pancake often includes bits of chewy konnyaku (konjac jelly) and, most notably, sujikon—a rich, slow-cooked mixture of beef tendon (suji) and konnyaku stewed in soy sauce, mirin, and sugar. This addition offers a textural contrast and a profound umami depth that elevates the pancake from a simple snack to a satisfying, complete meal. It embodies the Osakan ethos of kuidaore, or eating until you drop, where even the simplest dishes are crafted with great care and a focus on balanced, powerful flavors.

The Pilgrimage to Yamamoto: Experiencing the Original Negiyaki

Visiting Juso and not dining at Yamamoto is like going to Paris and bypassing the Eiffel Tower. Finding the restaurant is part of the journey. Nestled just off one of the main shopping arcades, its exterior is modest and understated. There is no grand sign, only a simple noren curtain hanging above the entrance and, more often than not, a small, patient line of people waiting outside. The scent of grilled onions and savory soy sauce serves as your true guide. Stepping inside is like entering a culinary time capsule. The space is dominated by a long, gleaming teppan grill stretching the length of the counter. This is the stage, and the chefs are the performers. Customers sit shoulder-to-shoulder on basic stools, captivated by the performance unfolding before them.

The air is thick with steam and the steady clinking of metal spatulas against steel. The chefs, dressed in simple uniforms and headbands, move with an efficiency born of decades of experience. There is no wasted motion. They ladle the green-speckled batter onto the grill, spreading it into a perfect circle. They skillfully scatter fillings, flip the pancakes with a flick of the wrist, and press down just right, creating a surface both charred and tender. The menu is straightforward, centered on the star of the show. While various combinations are available, the one to order on your first visit is the legendary Sujinegi. This classic dish is the standard bearer, filled with a glorious mixture of gelatinous beef tendon and konnyaku.

Watching your Sujinegi being prepared is an essential part of the experience. You see the fresh ingredients, hear the sizzle, and feel the heat radiating from the grill. When it’s finally ready, it isn’t whisked away to a plate in the back. Instead, it’s slid directly in front of you, right on the hot teppan, which keeps it warm until the last bite. The chef brushes it with a glossy layer of soy sauce. A wedge of lemon is placed beside it. The first bite is a revelation. The initial taste is the deep, savory soy sauce, quickly followed by the bright, acidic kick of lemon. Then comes the complex sweetness of cooked green onions, far removed from their raw, pungent state. The texture itself is a journey: the slight crispiness of the pancake’s surface gives way to a soft, yielding interior, punctuated by the firm chew of the konnyaku and the meltingly tender, collagen-rich pieces of beef tendon. It’s a symphony of flavor and texture that feels both rustic and remarkably refined. It’s the taste of Juso, the taste of history, served hot and fresh on a steel plate.

Beyond the Birthplace: Exploring Juso’s Teppanyaki Tapestry

While Yamamoto is revered as the sacred site for negiyaki purists, it is far from the only player in Juso’s dynamic culinary landscape. The charm of this neighborhood lies in its density and variety. To truly grasp its food culture, one must wander, get a little lost, and follow their instincts. Scattered throughout the alleys and arcades are dozens of other okonomiyaki-ya and teppanyaki spots, each boasting a loyal clientele and its own distinctive twist on the classics. Exploring these alternatives uncovers the subtle differences and personal touches that characterize neighborhood cooking.

Picture turning down a narrow side street, away from the main road, and noticing a small establishment with a faded red lantern gently swaying outside. Inside, you might discover a tiny, family-run place with just a few counter seats and an elderly woman behind the grill — a grill she has tended for fifty years. Her negiyaki might be a bit different—perhaps she uses a unique blend of flours or adds a secret ingredient to her dashi. The atmosphere is cozy; conversations flow naturally between the owner and regular customers. These are the spots where you don’t simply eat a meal, but participate in a slice of local life. Here, you might also find other teppanyaki staples prepared to perfection. Order a plate of yakisoba, the classic Japanese fried noodles, and watch as they’re skillfully tossed with pork and vegetables on the grill, deglazed with a splash of sauce that sends a plume of fragrant steam into the air. Or try a tonpeiyaki, a simple yet divine dish of thinly sliced pork grilled and wrapped in a fluffy, lightly cooked omelet, drizzled with sauce and mayonnaise. It’s comfort food at its finest.

Other venues offer a more modern take. You may come across a lively izakaya popular with a younger crowd, where negiyaki is served alongside an array of small plates and an extensive sake selection. Their version might be a bit more refined, perhaps featuring premium Kujo onions from Kyoto or unconventional fillings like cheese and tomato. This diversity is what makes Juso’s food scene so captivating. It’s a living ecosystem, not a museum. The tradition established by Yamamoto forms a solid foundation, but on top of it, countless other chefs create their own unique expressions of Osaka’s konamon spirit. The best advice for any visitor is to visit Yamamoto for the quintessential historical experience, then dedicate a second evening to wandering freely, letting chance and curiosity guide you to your own personal discovery.

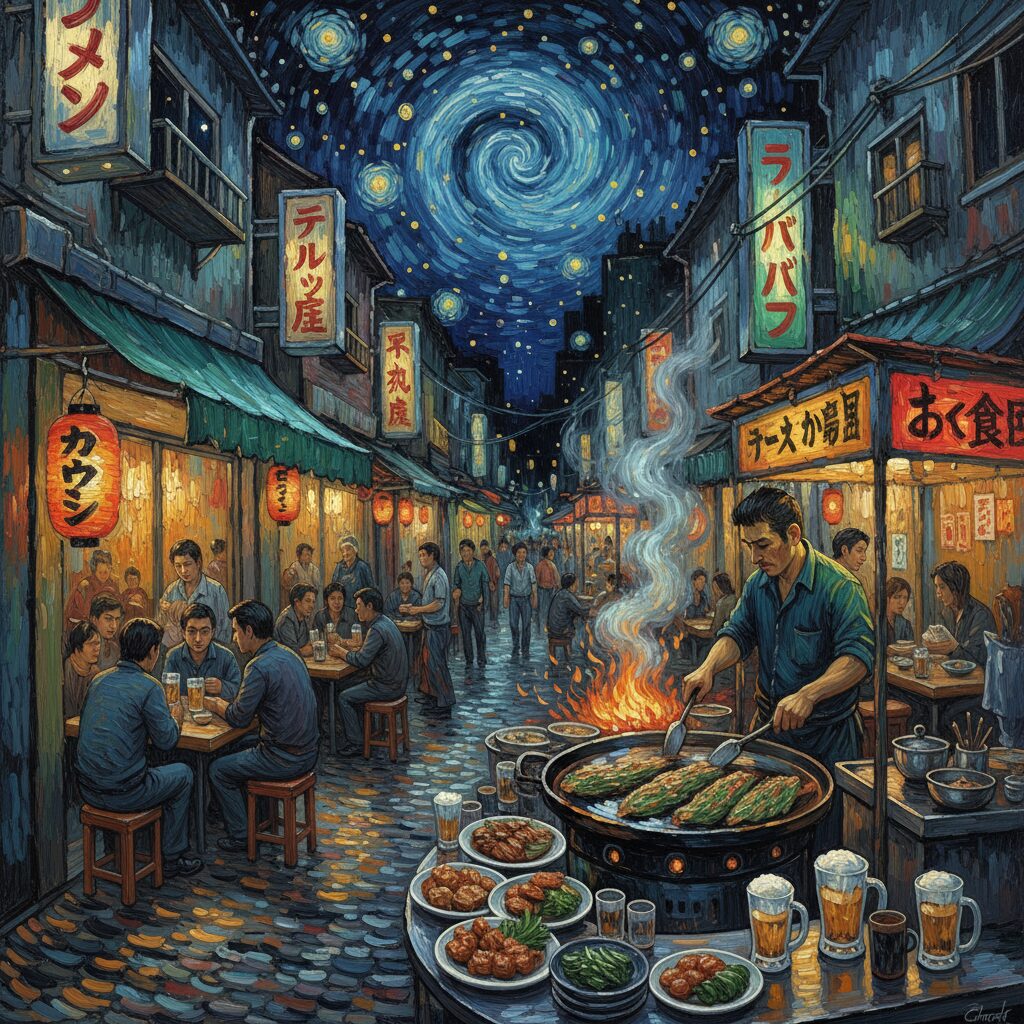

Juso After Dark: A Labyrinth of Flavor and Neon

As dusk falls over the Yodogawa River, Juso undergoes a remarkable transformation. The daytime appearance of a bustling shopping district fades away, giving rise to its nocturnal character, glowing vividly with neon lights and the warm radiance of paper lanterns. This neighborhood has long been one of Osaka’s most renowned and expansive entertainment areas—a place where the city unwinds. The maze-like alleys, which seem quaint by day, become lively corridors full of potential at night, each corner revealing a new scene.

The air thickens with mingled scents of grilled chicken from yakitori stalls, simmering broth from ramen shops, and the constant sizzle of teppan grills. The soundscape shifts as well. The daytime chatter of shoppers is replaced by clinking glasses, roaring laughter from busy bars, and faint melodies drifting from karaoke boxes. This is the realm of tachinomi (standing bars), where salarymen in suits stand shoulder to shoulder, quickly downing beers and highballs alongside skewers of grilled meat before catching the last train home. Cozy izakayas, their windows steamed up, offer refuge from the outside bustle. Here, groups of friends share large bottles of beer and sample menus filled with shareable dishes.

Juso’s nightlife is famously diverse and carries a reputation for being somewhat rough around the edges, which adds to its charm for those seeking an authentic, non-touristy experience. While it does include areas with more adult entertainment, these zones are generally separate and easy to avoid. For most visitors, the dominant feeling is one of joyful, uninhibited energy. It’s an ideal setting for a food crawl: starting with a negiyaki to settle your stomach, then moving to a tachinomi for a quick drink and snack, followed by a yakitori specialist for perfectly grilled chicken, and perhaps ending the night at a tiny, dedicated bar serving sake or shochu. Unlike formal dining, an evening in Juso is about movement, variety, and spontaneity. It rewards the curious and adventurous, offering a true glimpse into how Osakans celebrate and socialize.

A Cultural Crossroads: Juso’s Place in Osaka’s Narrative

To understand why Juso has become the vibrant hub it is today, you need to examine a map and consider the flow of people. Juso’s identity is deeply connected to the Hankyu Railway. It is more than just a station; it serves as a major junction, a crucial interchange where lines to the significant cities of Kobe and Kyoto, as well as the picturesque suburbs of Takarazuka, all converge. This strategic location, established in the early 20th century by the visionary industrialist Ichizo Kobayashi, destined Juso to remain a bustling center of activity. Millions of people pass through this station, and this steady flow of humanity created fertile ground for businesses catering to their needs: quick, affordable, and delicious food.

The neighborhood’s character was also shaped by its working-class roots. It grew as a residential and commercial area for the laborers and merchants who fueled Osaka’s industrial boom. There was no pretense here, no appetite for haute cuisine. What people wanted was food that was hearty, flavorful, and budget-friendly. This socio-economic backdrop gave rise to the entire konamon culture. Flour, water, and whatever vegetables and proteins were available were transformed on the teppan into satisfying meals. Negiyaki, relying on the inexpensive and abundant green onion, perfectly embodies this philosophy. It is culinary creativity born of practicality.

Beyond the railway and its working-class heritage, the presence of the Yodogawa River has also influenced Juso’s identity. The wide, open riverbank offers a natural space for recreation and gatherings. On summer nights, it becomes the setting for the Naniwa Yodogawa Fireworks Festival, one of Japan’s largest and most spectacular fireworks displays. On this single night, the gritty neighborhood transforms into the city’s premier viewing spot, attracting over a million spectators who picnic along the riverbanks and watch the sky. This event reveals another side of Juso—a place of civic celebration and shared experience. Additionally, the area hosts independent cultural venues like Theater Seven, a small cinema known for screening indie films and documentaries, adding an artistic edge to the neighborhood’s character. Juso is therefore more than just a place to eat; it is a microcosm of Osaka’s complex history—a story of transportation, industry, community, and the enduring appeal of a good meal.

Practical Guide for the Intrepid Food Explorer

Exploring Juso is an adventure, and as with any good adventure, a bit of preparation can make all the difference. This neighborhood has its own unique rhythm, and understanding it will help make your visit smoother and more rewarding.

The first thing to note is access. Juso Station is served exclusively by the Hankyu Railway, which is important for travelers used to JR lines or the Osaka Metro. From Osaka-Umeda Station, it’s a quick three-minute ride on any of the Kobe, Takarazuka, or Kyoto lines. Trains run frequently, so waiting times are minimal. Its close proximity to Umeda makes Juso an ideal, convenient choice for an evening outing, offering a distinct atmosphere just minutes from the city center.

The best time to visit Juso is in the evening. Many of the area’s most iconic restaurants and bars, including Yamamoto, don’t open until late afternoon or early evening, usually around 5:00 PM. The neighborhood truly buzzes after 6:00 PM on weekdays, as commuters head home. Weekends are lively as well, with a more relaxed and unhurried vibe. While daytime visits are enjoyable for exploring shopping arcades, to truly experience Juso’s spirit, an evening trip is essential.

Here are a few local tips to improve your experience. Bring cash. Though Japan is increasingly credit card-friendly, many older, smaller, and traditional spots in Juso remain cash-only. Having enough yen will help you avoid awkward moments and enable you to enjoy the most authentic places. Don’t be intimidated by small venues or those without English menus. A smile, a polite “Kore o onegaishimasu” (“This, please”), and pointing at what others are eating will usually do the trick. At places like Yamamoto, the simple menu makes it easy to order by pointing. Lastly, remember that Juso is a true local neighborhood. Be respectful when taking photos, keep your voice low in quiet residential alleys, and appreciate the atmosphere as a welcome guest.

Juso’s Enduring Savory Legacy

A journey through Juso is a journey into the essence of Osaka’s culinary identity. It offers an experience that removes the polished façade of tourism and connects you to the core rhythms of the city. Here, beneath the hum of passing trains, you realize that the soul of Osakan cuisine is not just a list of renowned dishes, but the environment in which they are crafted and enjoyed: the warmth of a busy counter, the expertise of a skilled chef, the comfort of a humble meal made with pride. Negiyaki is more than a pancake; it embodies Juso’s spirit. It is simple, richly flavorful, and deeply rooted in the community it serves.

Leaving Juso, with the lingering taste of charred green onion and savory soy sauce on your tongue, you take away more than just a full stomach. You gain the understanding that the most rewarding travel discoveries often lie just one stop beyond the main attractions, in places where life is lived with passion and flavor. So, when you visit Osaka, by all means, enjoy the stunning sights of the castle and the dazzling lights of Dotonbori. But then, catch a Hankyu train for the short trip to Juso. Explore its streets, find a seat at a sizzling steel grill, and experience the difference firsthand. In that simple, perfect circle of negiyaki, you will taste the savory, vibrant heart of a city that truly loves to eat.