There’s a question that hums beneath the surface for many foreigners settling into life in Japan, especially in the densely packed, hyper-modern urban sprawl of a city like Osaka. You’ve finally unpacked. You’ve figured out the labyrinthine subway system. You have a perfectly functional, albeit comically small, bathroom in your apartment with a shower and a tub that’s just big enough for one person, provided you’re willing to fold yourself into a human pretzel. And yet, you see them. Tucked away on quiet side streets, nestled between apartment buildings and tiny ramen shops, are the sento. The public bathhouses. You see the tell-tale tall chimney, a relic from a coal-burning past, or the distinctive split noren curtains bearing the simple, elegant kanji for hot water: ゆ (yu). And the question forms, a quiet curiosity: Why? In an age of private, personal convenience, why would anyone leave their perfectly good apartment, walk down the street with a small basket of toiletries, and choose to bathe with their neighbors? In Tokyo, a sento visit might be framed as a quirky, retro experience, a nostalgic nod to a bygone era, something you do for the ‘gram. But here in Osaka, it feels different. It feels less like a trend and more like a utility, as essential and routine as the corner convenience store or the local post office. It’s not a performance; it’s a practice. It’s woven into the very fabric of daily life, a living, breathing institution that reveals more about the soul of this city than any observation deck or famous castle. To understand the Osaka sento is to understand the city’s unpretentious, pragmatic, and deeply communal heart. It’s where the city’s tough exterior melts away, leaving behind a raw, honest, and surprisingly warm community. This isn’t about sightseeing. This is about participating in a ritual that oils the gears of neighborhood life, a ritual that can, and perhaps should, become part of your own Osaka routine.

To truly grasp this unique form of hadaka no tsukiai, or “naked communion,” that defines the sento experience, read our article on Osaka’s bath culture and the art of getting real.

Beyond the Bathtub: Why the Sento Still Thrives in Osaka’s Concrete Jungle

The persistence of neighborhood sento in Osaka stems from more than just nostalgia or the absence of modern plumbing in older buildings, though these factors certainly contribute to its history. It represents a conscious decision made daily by thousands of Osakans: choosing the communal over the private, the ritual over the routine, and the spacious soak over the cramped shower. To truly understand this choice, one must look beyond the mere act of washing and recognize the sento for what it really is—a third space, a mental reset button, and a masterclass in the city’s core philosophy of high-value, low-cost satisfaction.

It’s Not About Being Clean, It’s About Getting Reset

For most modern users, the primary purpose of visiting a sento has shifted from cleanliness to therapy. Life in an Osaka apartment, especially for singles or young couples, revolves around compact efficiency. Your living room might double as your bedroom and dining area. Walls can feel thin, ceilings low. Outside, there’s a constant chorus of train announcements, bicycle bells, and the vibrant hum of commerce. The sento offers a powerful antidote to this sensory overload. Upon stepping through the noren curtain, you enter a different state of being. Removing your shoes, clothes, watch, and phone is a physical symbol of shedding the day’s worries and responsibilities. You strip away identities—as a salaryman, a student, a foreigner, a parent—and in the warm, echoing bathhouse, you become simply a body in search of warmth and relaxation. This is the essence of what the Japanese call `hadaka no tsukiai`, or “naked communion.” While in many parts of Japan this concept carries a formal, almost corporate sense of bonding, in Osaka it’s much more grounded. It’s not about closing business deals or deep conversations. It reflects a shared, unspoken recognition of mutual humanity. There is no pretense, no social hierarchy. The company president and the construction worker soak side by side in the same 42-degree Celsius water, equally subjected to the intense heat. This collective vulnerability fosters a subtle yet powerful sense of community without the need for words. It offers a mental reset, a deep-tissue massage for the soul, readying you for another day in the bustling city.

The Economics of the Everyday Soak

Osaka is a city founded on the principle of `kosupa`, or cost performance. Its people possess an innate sense for value, deeply appreciating getting the most for their yen. The sento stands as the ultimate example of `kosupa` wellness. For roughly 500 yen—less than a fancy latte—you gain an hour of pure, unfiltered bliss. You enjoy large tubs of perfectly heated water, high-pressure massage jets, a sauna, and a cold plunge pool. Trying to replicate this experience at a private spa or gym would cost ten times as much. Osakans grasp this balance instinctively. Why splurge on fleeting entertainment when investing a few coins secures a ritual that yields profound physical and mental benefits? This pragmatism characterizes the city’s spirit. While a Tokyoite might romanticize the sento’s Showa-era charm, the Osakan values its functional brilliance. It’s a supremely rational choice. You outsource your bathing to professionals and a facility designed for the perfect soak. Your home gas bill decreases, your small apartment bathroom stays cleaner, and you receive an experience your own tub can’t match. For some living in older, post-war wooden tenements (`nagaya`), the sento remains an everyday necessity. But for most, it’s an affordable luxury—a deliberate choice to transform a daily chore into a restorative ritual. This blend of practicality and pursuit of simple pleasures perfectly epitomizes the Osaka mindset. It’s not about extravagance; it’s about extracting the greatest joy and comfort from ordinary life.

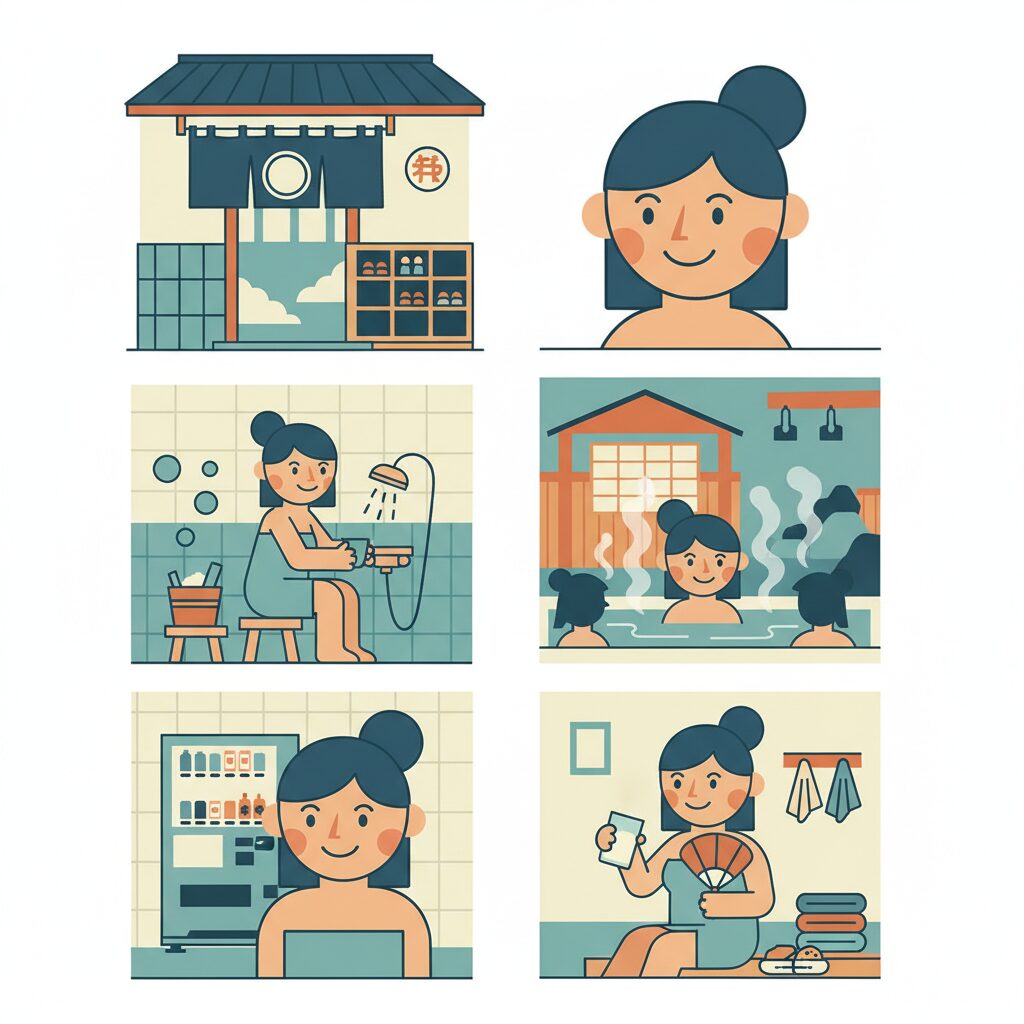

Decoding the Entrance: Your First Steps into a Neighborhood Sento

Your first visit to a local sento can feel overwhelming. The entrance buzzes with unfamiliar customs and objects, a silent language you haven’t yet mastered. But like most things in Osaka, the system is crafted for straightforward efficiency. There’s no secret handshake, just a series of simple, logical steps that quickly become second nature. Grasping this initial process is your key to fully enjoying the experience.

The Noren Curtain and the Bandai: Crossing the Threshold

The journey starts on the street. You’ll recognize the entrance by its distinctive split curtain, the `noren`, often dyed a deep blue or brown, prominently bearing the `ゆ` symbol. Parting it feels like stepping into another world, where the city’s pace immediately slows. The first thing you’ll see is the `getabako`, a wall of small wooden lockers for your shoes. Pick an empty one, slide your shoes inside, and take the wooden key. This key serves as your passport for the next hour; don’t misplace it. From there, you approach the heart of the operations: the `bandai` or a more modern front desk. The `bandai` is the traditional, elevated platform where the owner, often an elderly man or woman, sits like a watchful sentinel, overseeing both the men’s and women’s changing rooms. This high vantage point may feel unusual at first, but it’s a brilliant example of efficient design from an era before security cameras. The exchange here offers a perfect glimpse of Osaka’s communication style. There’s no elaborate `irasshaimase` (welcome). Instead, you’ll likely receive a nod, a grunt, or a simple “Hai, go-hyaku en” (“Yes, 500 yen”). This isn’t rudeness; it’s the comfortable shorthand of a neighborhood institution. You’re not treated as a distinguished customer; you’re a regular, a neighbor—even on your first visit. You pay your fee, and they’ll buzz you through the gate or point you to the appropriate changing room: 男 (`otoko`) for men, 女 (`onna`) for women. It’s a transaction stripped of any unnecessary ceremony, perfectly reflecting Osaka’s practical, no-nonsense spirit.

Gearing Up: The Sento Starter Kit

Once past the front desk, you enter the changing room, or `datsuijo`. Here, you have a choice. Many regulars bring their own `sento setto`, a small plastic or woven basket holding their preferred soap, shampoo, conditioner, and a small washcloth. This signals the seasoned visitor. However, the sento is fully equipped to welcome spontaneous guests. This is the `tebura` (empty-handed) option. For a small additional fee, you can rent a towel set (a small one for washing and a large one for drying) and purchase single-use packets of shampoo and body soap. The soap often arrives in a tiny, nostalgic box reminiscent of a cereal prize. This flexibility is central to the sento’s role as a casual, drop-in facility. There’s no need for advance preparation. You can decide to go on a whim as you walk home from work. Inside the bathing area, you’ll find stacks of small plastic stools and washbowls. The most iconic among them is the yellow `Kerorin oke`, a cheerful, durable basin that has been a sento staple for decades. It’s a piece of functional design so perfect it has become a cultural icon. Grabbing your stool and bowl, you’re now ready to join the communal ritual.

The Unspoken Choreography of the Bathing Area

Stepping from the changing room into the bathing area is an immersive sensory experience. The air hangs heavy with steam, carrying the scents of soap and minerals. The tiled room’s acoustics magnify every noise—the splash of water, the scrubbing of brushes, the quiet murmur of conversation—transforming them into an ambient, aquatic symphony. This is not a quiet, meditative space like a temple. It’s vibrant, practical, and governed by a set of unwritten rules everyone seems to instinctively understand. Learning this choreography involves more than mere etiquette; it’s about mastering how to share a space with care and respect, a crucial skill for life in densely populated Japanese cities.

The Kakeyu: The Essential First Step

Before you even consider sinking into those inviting hot tubs, there is one unbreakable rule: the `kakeyu`. This initial rinse is the most vital part of the entire sento ritual. Near the entrance to the bathing area, you’ll find a large basin of warm water with scoops or a dedicated shower station. Your task is to thoroughly rinse your whole body, especially your lower half, before entering any communal tubs. This is not a polite recommendation; it is the fundamental agreement of the public bath. You must wash away the dirt of the outside world to keep the shared water clean for everyone. Skipping this step is the gravest sento offense. You’ll earn silent, piercing glares from every `obaa-chan` (grandmother) in the room. In Tokyo, it might be a passive-aggressive look; in Osaka, there’s a good chance an `obaa-chan` will approach you and bluntly insist you wash properly. This isn’t meant to be hostile—it is community self-regulation, a straightforward but effective way of enforcing the rules that keep the shared space harmonious. They’re not reprimanding you personally; they’re safeguarding the bath’s integrity for all. Master the `kakeyu`, and you’ve passed the first and most important sento test.

The Washing Station: Your Private Spot in a Shared Space

After your `kakeyu`, you claim a washing station. Rows of low faucets and showerheads line the walls. You take a stool and basin, find an open spot, and set up your personal area. The etiquette here centers on spatial awareness. When you sit, you place your stool and basin on the tiled floor. When finished, you should rinse them with hot water and flip the stool upside down to drain, signaling that the spot is clean and ready for the next user. The cardinal sin at the washing station is splashing. In close quarters, no one wants a face full of soapy water. People naturally turn their bodies, aim showerheads downward, and keep their movements controlled to carve out a small bubble of personal space amid the crowd. It’s a graceful, almost instinctive dance of mutual consideration. This is where the real cleaning happens. You scrub thoroughly with a small towel that doubles as a washcloth. Men and women alike focus intently, working up rich lathers in a process that is both cleansing and invigorating. This isn’t a quick rinse—it’s a deliberate, careful ritual. Only when you are completely clean are you truly ready for the main event: the soak.

Mastering the Soak: Bathing Like a Local

The tubs, or `fune` (boats), form the heart of the sento. They vary in shape, size, and, most importantly, temperature. Approaching them requires some strategy and an understanding of the local customs that regulate their use.

The Temperature Challenge: From Atsuyu to Nuruyu

Most sento have several pools. Typically, there’s a main tub heated comfortably but very hot, around 41-42°C (106-108°F). Then there’s often the `atsuyu`, or “hot hot tub,” which can reach 44°C (111°F) or more. This is where seasoned regulars lounge contentedly, while newcomers barely dare dip a toe. There might also be a `nuruyu` (lukewarm bath), jacuzzi-style tubs with powerful jets (`jetto basu`) targeting your back and calves, and sometimes a specialty bath infused with herbs or minerals. The proper approach is to ease in slowly, allowing your body to adjust. Don’t just jump in. A brief soak, followed by cooling down at the edge, then another soak, is the common rhythm. For the brave, there is the `mizuburo`, the cold-water plunge. Alternating between the intense heat of the main bath or sauna and the shocking cold of the `mizuburo` is believed to boost circulation and is an integral part of the experience for many bathers. It delivers a visceral, exhilarating shock that leaves you feeling remarkably refreshed and energized.

The Towel Rule: On Your Head, Never in the Water

One of the most common mistakes foreigners make involves the small towel used for washing—it should never go into the bathwater with you. The tubs are reserved for clean, rinsed bodies only, and the towel, which may carry soap residue, is considered unclean. So, what do you do with it? There are two socially acceptable ways. The most common is to fold it neatly and place it on top of your head. This might look odd, but it’s perfectly normal and practical—it keeps the towel clean and close at hand. Alternatively, you can lay it on the tiled edge of the tub. Just be sure it never drops into the water. This small detail signals that you grasp and respect the customs of the space.

The Electric Bath (Denki Buro): Osaka’s Quirky Delight

Among the tubs, you might encounter a particularly unusual one: the `denki buro`, or electric bath. This small tub features two metal plates on opposite sides that pass a low-voltage electric current through the water. It’s undeniably one of the most uniquely Japanese—and distinctly Osaka-esque—bathing experiences. The sensation is strange. Positioned between the plates, your muscles tingle and contract involuntarily. It feels like thousands of tiny pins and needles, a deep, buzzing massage. For newcomers, it can be startling, but for regulars, it’s a cherished therapy for stiff shoulders and sore backs. The presence of a `denki buro` reveals much about Osaka’s character. It’s neither elegant nor refined. It’s a bit quirky, somewhat intense, and highly practical. It’s a straightforward tool for relief, and those who enjoy it really love it. Trying the `denki buro` is a rite of passage. Once you overcome the initial shock and come to appreciate its unique, twitchy comfort, you’ve tapped into a deeper, more distinctive layer of Osaka culture.

The Post-Bath Ritual: The Sento’s Social Heart

The sento experience continues even after you leave the water. In fact, some of the most significant parts of the ritual happen in the `datsuijo`, the changing room, once you’ve dried off. Here, the bathhouse’s functional space transforms into a genuine community lounge—a place to cool down, rehydrate, and reconnect with others.

The Changing Room (Datsuijo): More Than Just a Space to Dry Off

The `datsuijo` serves as the social heart of the sento. After the steamy, enclosed atmosphere of the bathing area, the changing room feels spacious and airy. It features classic amenities that have endured through time: a large analog weight scale that clicks satisfyingly underfoot; old, rumbling massage chairs costing 100 yen for a vigorous five-minute session; wall-mounted fans that slowly oscillate on hot summer nights. Lockers are often wooden, and clothes are kept in simple wicker or plastic baskets. This is where the quiet solitude of the bath shifts into real conversation. Neighbors share gossip, elderly men discuss the Hanshin Tigers baseball games, and mothers manage their lively, freshly scrubbed children. It’s like a living room for the neighborhood. One of the most striking aspects of this space for Westerners is the complete absence of body consciousness. People of all ages, shapes, and sizes towel off, dress, and relax without a trace of self-consciousness or judgment. In a world filled with idealized images of the human body, the sento changing room stands as a refuge of radical, unpretentious acceptance. Wrinkles, scars, and bellies are not hidden; they are simply part of the human landscape. This casual nudity isn’t sexualized—it’s normalized. It offers a powerful lesson in shedding insecurity, a freedom rooted in the shared understanding that beneath our clothes, we are all simply human.

The Holy Grail: The Post-Sento Drink

The final, crowning moment of the sento ritual is the post-bath drink. No visit is truly complete without it. Near the front desk, you’ll undoubtedly find a vintage glass-fronted refrigerator humming quietly, stocked with a specific, revered selection of beverages. The classic choice is milk, but not just any milk. Coffee milk (`kohi gyunyu`), known for its sweet, nostalgic taste, and fruit milk (`furutsu gyunyu`), a bright, fruity drink that evokes childhood, are favorites. These are always served in small, iconic glass bottles with paper caps that you pop open with a satisfying snap. The proper way to enjoy it is to place one hand on your hip, tilt your head back, and down the entire bottle in one smooth motion. For adults, a cold can of beer is an equally popular—and arguably more Osakan—option. Few pleasures match the crisp, cold lager after being steamed to perfection in the `atsuyu`. This simple act of rehydration perfectly concludes the experience. It cools you from within, replenishing lost fluids and sealing the feeling of complete renewal. It’s the ultimate affordable reward, a small, perfect moment of satisfaction that frames the entire ritual. This appreciation for life’s simple, well-earned joys lies at the heart of Osaka’s working-class spirit.

Sento as a Microcosm of Osaka Society

If you truly want to grasp what makes Osaka vibrant, spend a few evenings at a local sento. This modest establishment serves as a perfect microcosm of the city’s social dynamics, communication styles, and core values. It’s where abstract cultural ideas transform into visible, tangible behaviors. It acts as a living classroom for anyone wanting to understand Osaka life.

Direct, Not Rude: The Osaka Communication Style in Practice

There’s a common stereotype that people from Osaka are more direct, loud, and expressive compared to the famously reserved Tokyo residents. The sento is where you can see this firsthand and, more importantly, comprehend the reasoning behind it. For example, if you break a rule—like forgetting your `kakeyu` or letting your towel touch the water—you’re more likely to be corrected verbally in Osaka. An older regular might say, “Ani-chan, karada aratte karaやで” (“Hey kid, wash your body first”). To outsiders, this might come across as brash or confrontational, but understanding the intent is key. It’s not personal criticism; it’s a practical, efficient, and ultimately communal gesture. The aim is to preserve the shared environment for everyone’s benefit. The correction targets your action, not your character. This straightforwardness is a form of social efficiency. Why waste time with subtle hints and resentful looks when a few clear words solve the issue instantly? This reflects the Osaka mindset: pragmatic, solution-driven, and less concerned with the intricate politeness that can sometimes cloud meaning elsewhere in Japan. It’s a kind of tough love that keeps the community functioning smoothly.

A Community of Strangers

The sento cultivates a distinctive kind of community. You might visit the same bathhouse for years without ever learning the names of the regulars, yet you’ll come to know them through their habits. You’ll recognize the old man who always arrives at 7 PM to spend ten minutes in the `denki buro`. You’ll know the father and son who visit every Saturday afternoon. You’ll nod to the woman who consistently uses the corner washing station. This community is built on shared presence rather than active interaction. It fosters a powerful, quiet sense of belonging. In a sprawling, anonymous city, the sento offers a human scale and reminds you that you belong to a particular place—a neighborhood with its own rhythm and characters. This forms the foundation of local life, creating a sense of place that is increasingly rare today. It’s a calm, stable social network that requires no names or formal introductions, held together by the simple, repeated act of sharing hot water.

Foreigner Misunderstandings: Tattoos and Timidity

Two main concerns often stop foreigners from trying a sento: fear of being turned away because of tattoos and unease about public nudity. The reality is far more nuanced. The strict tattoo ban is mostly found in high-end onsen resorts and large spa complexes, where the link to the `yakuza` (organized crime) impacts their image. However, humble neighborhood sento often differ. Many are more lenient, especially when it comes to smaller, non-traditional tattoos on foreigners. The golden rule is to politely ask at the front desk, but you’ll often find that local bathhouses follow a practical don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy, or simply don’t mind. This pragmatism is, once again, distinctly Osakan. Regarding nudity, fear of being stared at is almost entirely imagined. As mentioned, the sento is a great equalizer. Nobody is there to judge your body; everyone is focused on cleansing, relaxing, and soaking aching muscles. After about five minutes, you’ll realize you’re invisible, just another person in the steam. The initial unease is a small price for the profound sense of freedom and acceptance that follows.

Finding Your Neighborhood Sento: An Explorer’s Guide

When you’re ready to take the plunge, discovering a sento becomes a rewarding treasure hunt. They aren’t always marked by flashy signs but are woven into the neighborhood’s architecture, making spotting them part of the adventure.

Look for the Chimney

The classic and unmistakable feature of a traditional sento is the tall, slender chimney that rises above residential rooftops. Historically, these chimneys were vital for wood- or coal-fired boilers used to heat the water. Although many have switched to gas, the chimneys often remain as proud landmarks. As you approach, watch for the `noren` curtain, the `ゆ` symbol, and possibly a small sign displaying the bath’s name. Sometimes, you might catch the faint scent of steam and soap in the air or hear the distant, echoing sounds of water from the street.

Exploring Different Neighborhoods

Not all sento are the same, and their character often mirrors the neighborhood they’re in. A sento located in historically working-class areas like Nishinari or Taisho might feel more raw and old-school, frequented by older patrons with a no-frills atmosphere. In contrast, one in a residential area such as Showa-cho or near Tennoji might attract more families and have a slightly more modern vibe. Some newer or renovated sento, often called “designer sento,” can feature modern art, unique lighting, or special carbonated baths. It’s also important to distinguish traditional sento from “super sento.” Super sento are much larger, modern facilities that often include restaurants, massage services, and multiple themed baths. While they’re fantastic, they provide a different, more commercial experience. The true spirit of the practice, the genuine neighborhood connection, lives on in the small, family-run `machi no o-furo-ya-san`—the town’s local bath shop.

A Final Thought: The Warmth Beyond the Water

Incorporating a sento visit into your daily routine in Osaka means more than simply discovering a better way to bathe. It involves actively engaging in a living tradition that embodies the city’s spirit. It means embracing a practical, value-driven mindset that appreciates simple, meaningful pleasures over costly extravagances. It is understanding a style of communication that values clarity and communal harmony rather than indirectness. It fosters a sense of belonging—not in a noisy bar, but in the quiet, shared ritual of the soak. The warmth of the sento lingers long after you leave. It feels like walking home on a crisp autumn evening, your skin tingling and your body warmed to the core. Your mind is calm, cleared of the day’s noise. You exchange a nod with another person leaving the sento, their face glowing with the same serene contentment. In that moment, you are neither a foreigner, tourist, nor outsider. You are a neighbor. You are part of the rhythm. And you realize, on a deep, physical level, what it truly means to live in Osaka.