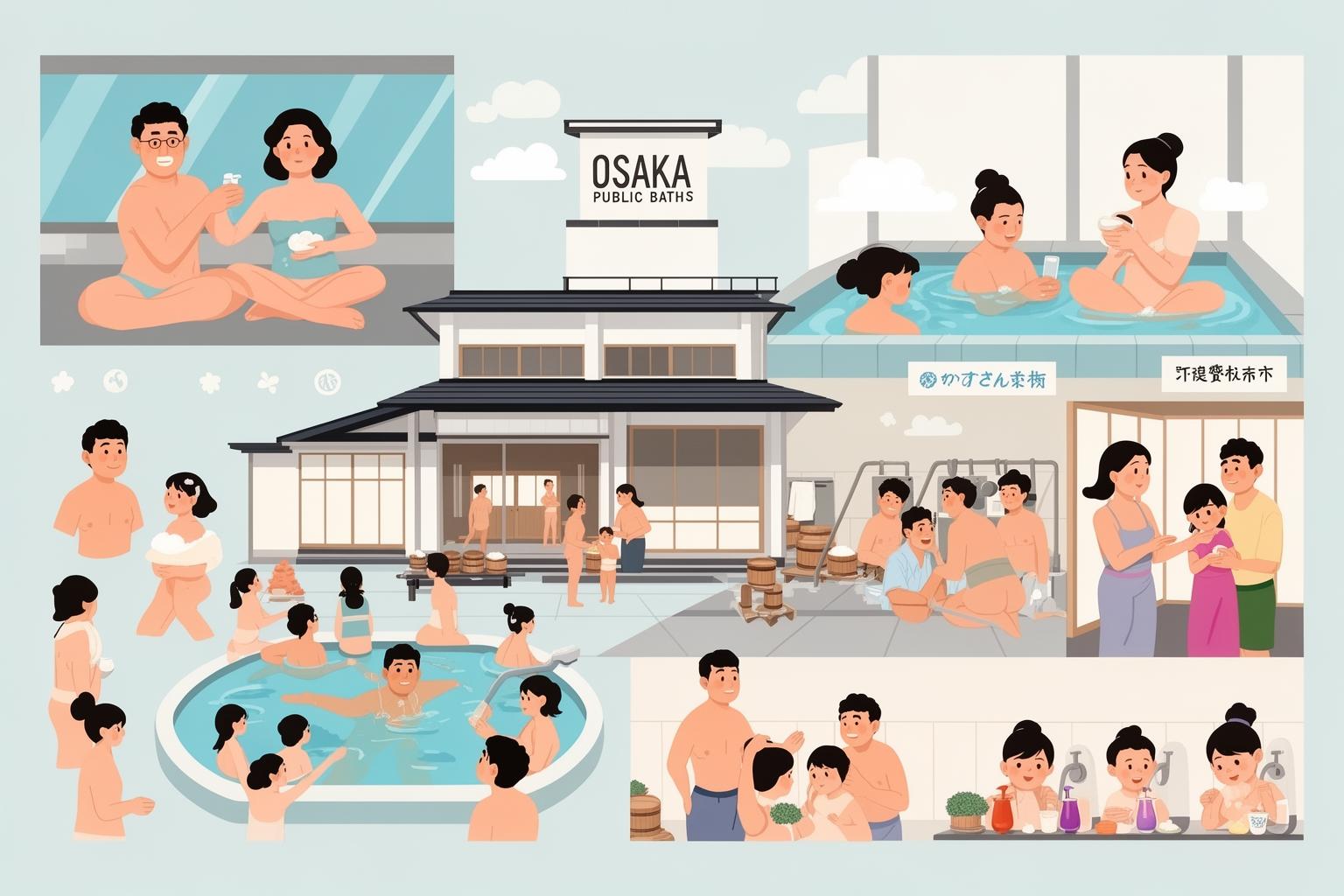

Step off the neon-drenched streets of Osaka, away from the electric pulse of Dotonbori and the towering ambition of Umeda Sky Building, and you’ll find a different kind of warmth. It’s a warmth that steams from behind humble noren curtains, a warmth that has cradled communities for generations. This is the world of the Japanese sento, the neighborhood public bath, and in a city as famously down-to-earth as Osaka, it’s the absolute soul of daily life. Forget choreographed tourist trails for a moment. To truly understand this city, you need to shed your inhibitions, grab a tiny towel, and immerse yourself in the art of the communal bath. It’s more than just getting clean; it’s a rhythmic ritual of relaxation, a social hub where stories are shared in hushed tones, and a living museum where the traditions of old Japan gently persist against the rush of the modern world. This isn’t just about a bath; it’s about belonging, even if just for an evening. It’s about finding a quiet, profound connection to the heart of the city, one blissful soak at a time.

To truly understand this city, you need to shed your inhibitions, grab a tiny towel, and immerse yourself in the art of the communal bath, a ritual that connects you to the enduring merchant soul of Osaka.

The Curtain Raiser: Stepping into Another Time

Your journey starts at the entrance. Seek out a building with a traditional temple-style roof, or perhaps a tall, slender chimney (entotsu) stretching toward the sky—a clear indication of the boiler inside. The true gateway, however, is the noren, a split fabric curtain, often dyed a deep indigo blue and displaying the iconic kanji for hot water, ゆ (yu), or its hiragana equivalent, ゆ. Pushing it aside feels like a purposeful step of transition, leaving the city’s noise behind and entering a sanctuary of steam and calm.

Inside, the first thing you’ll find is the getabako, a wall of small wooden lockers for your shoes. Locate an empty one, slip your shoes inside, and take the wooden key. This simple gesture marks your first step in shedding the outside world. The air already feels different here—heavier with humidity, carrying the faint, clean scent of soap and warm wood. You’ll approach the bandai or front desk, where an attendant, often an elder who has likely witnessed generations of bathers, will greet you. The fee is quite modest, usually just a few hundred yen paid in cash, a small price for the immense comfort ahead. From here, you’ll be directed to your side of the establishment, as sento are strictly divided by gender. Look for the characters for man (男, otoko) or woman (女, onna) on the curtains leading to the changing rooms.

The Unveiling: The Changing Room and the Tiny Towel

The changing room, or datsuijo, is a calm space for quiet preparation. It’s typically a tatami-matted or wooden-floored area lined with lockers or, more traditionally, wicker baskets (kago) for storing your clothes. These spaces have a comforting, well-worn ambiance. The scent of aged wood, the sight of vintage posters advertising classic Japanese drinks, and the gentle hum of a large fan in summer all enhance the feeling of timelessness. This is where you fully undress. For first-timers, this can be the most intimidating part, but it’s important to know there is absolutely no judgment here. Nudity in the sento is entirely non-sexual and natural; it’s the great equalizer. Everyone, from company presidents to construction workers, stands equal in the bath. This shared openness forms the basis of the sento’s communal spirit.

Regarding your gear, while many modern “super sento” offer a wide range of amenities, the traditional neighborhood sento operates on a bring-your-own basis. You’ll need two towels: a large one to dry off completely at the end, and a small, thin one, often called a tenugui. This small towel is your most essential accessory. It serves several purposes: as a washcloth in the shower area, as a modesty cover when walking between the washing area and the baths, and as a cushion for your head while soaking. You’ll also need your own soap, shampoo, and conditioner. If you forget anything, don’t worry—most sento sell these items in small, single-use packets at a modest cost. Pack everything you need for the bathing area into a small waterproof bag or plastic basin, which are often available to borrow.

The Sacred Ritual: Washing Before You Soak

Before even thinking about dipping a toe into the main baths, you must wash first. This is the most important rule of sento etiquette, an essential act of respect for the shared water and your fellow bathers. The bathing area is lined with washing stations, each furnished with a low stool, a faucet with hot and cold taps (or a modern shower wand), and a bucket. Sit on the stool—washing while standing is considered poor manners since you might splash others—and begin to scrub. Lather your small towel and wash every inch of your body thoroughly. When finished, use the faucet or shower to rinse off every trace of soap. Be sure to rinse your stool and the surrounding area clean for the next person. Some bathers start with kakeyu, a practice involving scooping a few buckets of hot water from a small basin near the bath entrance and pouring it over the body to acclimate to the temperature before moving to the washing station. This entire routine should not be rushed; it is a meditative preparation, cleansing both body and mind, preparing you for the pure relaxation of the soak.

The etiquette concerning the small towel continues here. While soaking in the main baths, this towel must never enter the bath water as it is considered unclean. Locals skillfully fold theirs and place it on their head, a technique believed to help prevent dizziness from the hot water. Others leave it on the tiled edge of the tub or on a nearby rock in a rotenburo (outdoor bath). Observing this small but important detail clearly shows that you understand and respect the local customs.

Immersion Therapy: The Art and Variety of the Bath

Now, the moment of bliss has arrived. With your body thoroughly scrubbed clean, you are ready to step into the baths. Enter slowly, allowing your body to adapt to the heat. The main tub, called the yubune, is usually heated to a cozy 40-43°C (104-109°F). It’s warm, but your body will appreciate it. The goal here is to soak, letting the heat penetrate your muscles and dissolve the stress of the day. This is a place for quiet reflection, not for swimming, splashing, or loud conversations. The water is a shared space of tranquility.

Many sento provide a charming range of baths. You may find a jetto basu (jet bath) with strong streams of water massaging your back and shoulders, or a denki buro (electric bath), which passes a mild electric current through the water. Approach the denki buro carefully; the tingling sensation is unusual at first but cherished by many regulars for its reputed therapeutic benefits on stiff muscles. There is almost always a mizuburo, a small cold water tub. The hallmark of an experienced sento-goer is mastering the art of alternating between hot and cold baths. The initial shock of cold water is intense, yet it stimulates circulation and leaves you feeling amazingly clear-headed and energized. This practice requires bravery but offers great rewards.

Take a moment to observe the bathing area. The décor enhances the experience. Many traditional sento boast stunning murals of Mount Fuji painted on the tiles, a custom dating back to the early 20th century intended to give bathers a sense of vast beauty and escape. Others display intricate tile mosaics of koi fish, pastoral scenes, or local landmarks. These artworks serve not only as decoration but as an essential part of the sento’s character and a source of local pride.

The social dimension is subtle but meaningful. While some prefer to soak in silence, the sento is fundamentally a community space. You might catch light conversations among neighbors sharing local news or quiet laughter. A simple nod or slight bow to fellow bathers when entering or leaving a tub is a courteous gesture. Don’t feel obliged to socialize, but remain open to the warm, unspoken sense of community that pervades the steamy air. It is in these calm moments of shared relaxation that the true charm of the sento emerges.

The Afterglow: Post-Bath Traditions

When you feel completely relaxed and your skin is glowing, it’s time to come out. However, the ritual isn’t quite finished yet. Before returning to the changing room, use your small towel to wipe off as much excess water from your body as possible. The aim is to prevent dripping all over the datsuijo floor, a small but thoughtful gesture for others. Once back in the changing room, you can use your large, dry towel to thoroughly dry yourself.

This post-bath period is a treasured part of the experience. Take it slow. Many changing rooms offer amenities like coin-operated hair dryers, fans, and sometimes even vintage massage chairs that vibrate and knead your newly relaxed muscles into a state of complete bliss. This is also the moment for rehydration, and the traditional post-sento drink is a ritual in itself. Keep an eye out for the old refrigerators, often stocked with small glass bottles of milk—plain, coffee, or fruit-flavored—and Ramune, the iconic Japanese soda with a marble in its neck. There’s nothing quite like the sensation of drinking a cold bottle of fruit milk after a hot bath. It’s a taste of pure, nostalgic Japan.

Many sento also feature a small relaxation area or lobby where you can sit on a tatami mat or a vinyl couch, watch television, and let the peaceful feeling linger. This is where the sense of community extends beyond the bath itself. You might see regulars playing a game of shogi (Japanese chess) or simply sharing a quiet moment of camaraderie before heading back out into the world, refreshed and renewed.

A Note for the Modern Bather

In an era of private bathrooms and instant gratification, the neighborhood sento can seem like a relic from another time. Indeed, their numbers have steadily decreased over the decades. Yet, they remain important cultural institutions. For women traveling or living in Osaka, the onna-yu provides a unique space of safety and solidarity. The shared bath experience creates a quiet, supportive environment that is both empowering and deeply comforting. There’s no need to worry about not knowing what to do; local women are almost always welcoming and understanding. The best strategy is to simply observe and follow their example. Their movements form a graceful, unspoken language of respect and tradition.

A common question concerns tattoos. While many onsen (natural hot springs) and larger spa facilities still enforce strict rules against tattoos due to their historical links to the yakuza, neighborhood sento are often much more tolerant, especially in a city as famously laid-back as Osaka. Policies vary, but in most local bathhouses, small tattoos rarely cause any issues. If you have extensive tattoos, it’s wise to check the specific sento’s policy in advance if possible, but overall, you’ll generally find a more welcoming attitude here than elsewhere.

Finding a sento is an adventure in itself. They are often tucked away on quiet residential streets, their presence indicated only by the subtle signs mentioned earlier. Exploring these backstreets and uncovering a hidden gem is part of the charm. Each sento has its own distinct character, ranging from Showa-era establishments that feel perfectly preserved in time to more modern versions with updated facilities and special features like herbal baths or saunas. Don’t hesitate to try different ones; each offers a slightly different glimpse into the heart of its neighborhood.

The Warm Embrace of Community

Visiting a sento in Osaka means more than just bathing; it is engaging in a living tradition, a daily ritual that purifies the body and soothes the spirit. This affordable, accessible form of wellness has supported Japanese communities for centuries. Within the steamy, inviting walls of the bathhouse, social distinctions fade away, replaced by simple, genuine human connection. You leave not only with refreshed skin but also with a lighter heart and a richer appreciation of the surrounding culture. So, take a deep breath, part the noren curtain, and step into the warm, inviting water. The city of Osaka awaits to welcome you in its most authentic and restorative way.