It’s seven o’clock on a Tuesday in Osaka. The summer air, thick and heavy like a wet wool blanket, still clings to the asphalt even after the sun has dipped below the horizon. The neon lights of the shotengai are buzzing to life, the clatter of a thousand bicycles heading home mixes with the sizzle of takoyaki stands, and your shirt is sticking to your back in that uniquely Osakan way. At the end of a day like this, a day spent navigating the crowded trains, the endless meetings, or the labyrinthine underground malls, the thought of a simple shower in a cramped apartment bathroom can feel less like a relief and more like another chore. But here, in this city of pragmatic pleasures, there’s a better way. A way to wash off not just the grime of the day, but the weight of it, too. It’s a ritual that hums beneath the surface of daily life, a cornerstone of the community hiding in plain sight. It’s time to go to the sento.

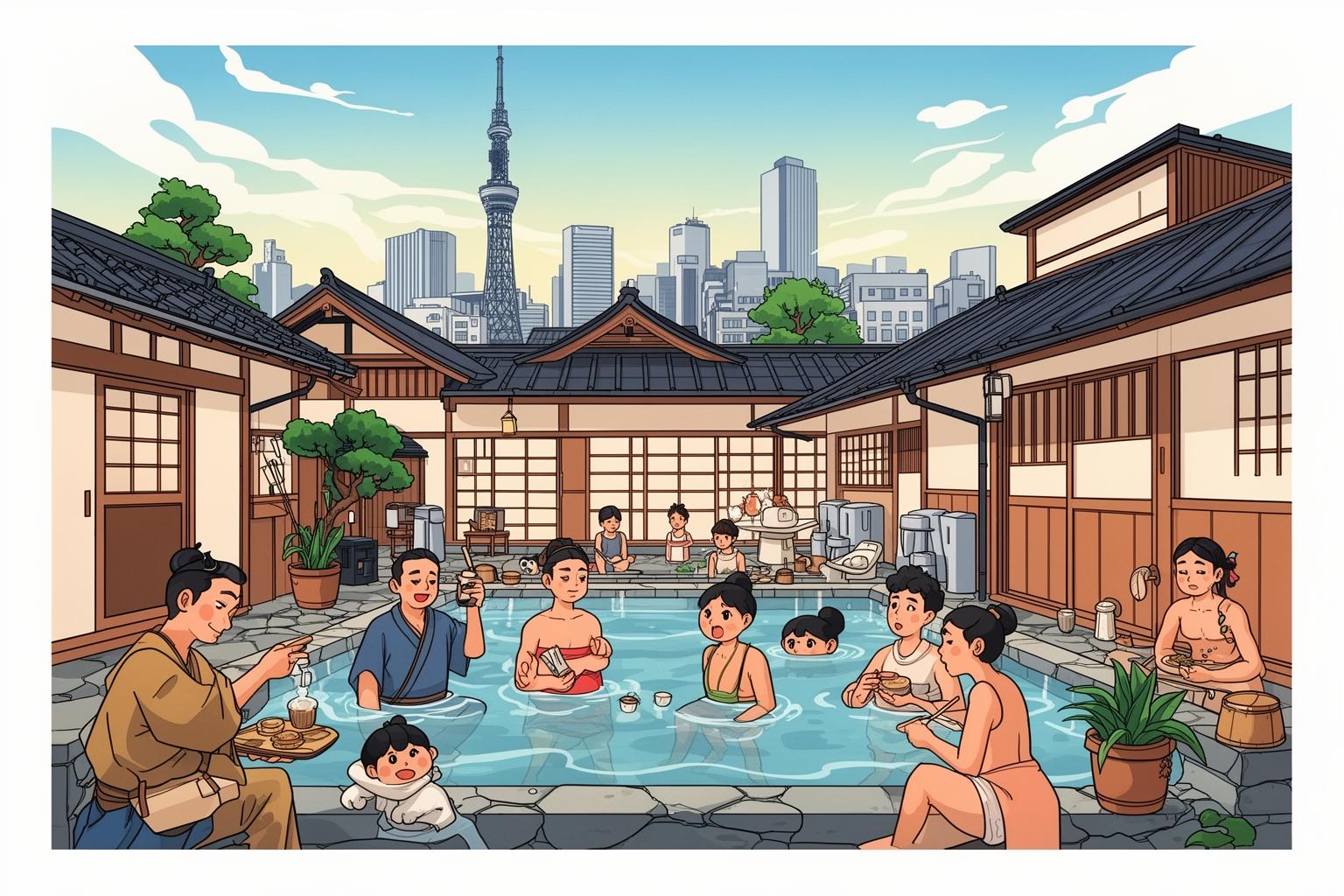

Now, let’s get one thing straight. This isn’t about the grand, tourist-filled onsen resorts you see in travel brochures, with their perfectly manicured rock gardens and serene mountain views. This isn’t about the sprawling, theme-park-like “super sento” complexes on the edge of town with wave pools and water slides. This is about the neighborhood sento, the public bathhouse. It’s the place with the tall, slender chimney poking up between residential buildings, the place with the faded blue and red noren curtains flapping in the entrance, the place that costs about the same as a fancy coffee. For a visitor, it might seem like a relic, a throwback to a time before every home had its own plumbing. But for the people who live here, the sento is not a museum piece. It’s the city’s communal living room, its unofficial therapy office, and its most honest social club, all rolled into one steamy, tile-lined package. It’s where you see the real Osaka, raw and unfiltered. It’s where the city’s famously loud, pragmatic, and warm-hearted character is on full display. Forget what you think you know about Japanese quietness and reserve. To truly understand how this city ticks, you need to learn how to wind down like an Osakan. You need to grab a small towel, get naked, and soak.

If you’re looking for another quintessential Osaka ritual to start your day, consider experiencing the local culture at a classic Osaka kissaten.

The Sento as Osaka’s Social Hub: Beyond Just Getting Clean

The first time you push aside that noren curtain, a wall of warm, humid air greets you, offering a sensory introduction to a different world. It carries the fresh scent of countless soap brands, the subtle mineral hint of heated water, and something else—the vibrant sound of life. Unlike the hushed reverence found in a Kyoto temple or the more reserved atmosphere of a Tokyo sento, an Osaka bathhouse often buzzes with audible energy. It resonates with the lively rhythm of Osaka-ben, the local dialect that feels less like a conversation and more like a friendly argument. You’ll hear grandmothers, their voices rasping from years of lively chatter, sharing neighborhood gossip. Fathers laugh as they try to control their splash-prone children. Salarymen exhale contentedly as they sink into the hot water, their work personas dissolving with the steam.

This is the Osakan expression of a concept known throughout Japan as “hadaka no tsukiai,” or “naked communication.” Elsewhere in the country, this might show as quiet, unspoken camaraderie—a shared vulnerability that builds a subtle bond. In Osaka, it’s simply communication. Loud, direct, and utterly free of pretense. Status, wealth, and occupation mean nothing when everyone is stripped down to their birthday suit. The CEO of a major corporation might be borrowing shampoo from a truck driver because he forgot his own. A university professor could receive unsolicited, yet well-meaning, advice about his bad back from a retired fishmonger. This is the great equalizer. The water washes away uniforms and social masks worn all day, exposing the raw human core beneath.

I recall one of my first visits, carefully navigating the washing area, trying not to break any rules or embarrass myself. An elderly woman with a shock of permed white hair, scrubbing her back with surprising vigor, caught my attention. She stopped, pointed at my back with her loofah, and said rapidly in Osaka-ben, “Son, you can’t reach that spot. C’mon.” Before I could protest, she was scrubbing my back with the power of an industrial sander, all the while asking where I was from, if I was eating well, and why I wasn’t married yet. It wasn’t intrusive; it was caring. It was the kind of blunt, straightforward intimacy that defines the city. This isn’t the polite, reserved “friendliness” you read about in guidebooks. It is an active, participatory warmth that pulls you into the community, whether you’re ready or not. It’s a stark contrast to Tokyo, where keeping polite distance is often the norm. In an Osaka sento, maintaining distance feels strange. Why be quiet when you can talk? Why be alone when you can connect?

Navigating the Unspoken Rules: Your First Sento Visit

Despite its lively atmosphere, the sento follows a deeply rooted set of rules and etiquette. These guidelines are rarely posted on the walls because they are expected to be inherently understood. This can cause the most anxiety for newcomers, but mastering the flow unlocks the entire experience. Rather than seeing them as a list of restrictions, think of them as a shared dance—a choreography that enables hundreds to use the communal space harmoniously.

Before You Even Enter

Your journey starts on the street, where you’ll spot visual signals. The most noticeable is the tall chimney, proudly signaling hot water inside. Then, the entrance: perhaps a traditional tiled roof with a short noren curtain displaying the character for hot water, 「ゆ」(yu), or the bathhouse’s name. Once inside, you’ll find the getabako—a wall of small wooden shoe lockers. Pick an empty slot, slip your shoes in, and take the wooden key. This key is your pass to the next stage. What should you bring? Essentials include a large towel for drying, a small towel for washing and modesty, as well as soap and shampoo. Don’t worry if you forget; attendants usually sell “tebura sets” (empty-handed sets) for a few hundred yen, containing a small rental towel and single-use toiletries. Regulars often arrive with personalized baskets packed with their favorite shampoos or classic soap bars, which adds to the charm.

The Changing Room (Datsuijo)

Holding your shoe locker key, you approach the bandai—a raised platform where the attendant sits—or a modern front desk. Here, you pay the bathing fee, which in Osaka is regulated by law and typically just under 500 yen. The attendant, often an elderly person familiar with everything, will accept your payment and direct you to the correct changing room: blue for men (男), red for women (女). The changing room buzzes with quiet activity—wicker baskets or lockers line the walls, old-fashioned scales, and coin-operated hair dryers occupy a corner. Find an empty locker and prepare for the moment of truth: undressing completely. No swimsuits are allowed in the sento. For many foreigners, this is the biggest cultural adjustment, but it’s essential to understand there is nothing sexual about it. Swimsuits are seen as unhygienic because they can introduce outside dirt into the clean bathing water. Everyone is in the same situation, and truly, no one is watching. Visitors come to relax, not to judge. Your small towel becomes your modesty shield as you walk from the changing room to the bathing area. This small gesture demonstrates your understanding of the etiquette.

The Bathing Area (Yokujo)

Sliding open the glass door, you’re greeted by a rush of steam—welcome to the main event. Before you even think about entering the steaming tubs, you must follow the cardinal rule of Japanese bathing: wash yourself thoroughly. Locate an open washing station, each equipped with a low plastic stool, mirror, faucet with hot and cold taps, and a handheld shower. This is where you do the hard work of cleansing. Sit down—never stand to avoid splashing neighbors—and scrub every inch of your body with soap. Lather your hair, then rinse completely. Only when you are squeaky clean are you allowed to enter the communal baths. This practice isn’t just about hygiene; it’s a sign of respect towards your fellow bathers. Everyone shares this water, and there is an unspoken agreement that all have made the effort to keep it pure.

Two other key rules apply in the bathing area. First, your small wash towel must never enter the bath water. Fold it neatly on your head or set it aside by the tub. Letting it soak in the bath is a major faux pas. Second, long hair should be tied up to prevent it from trailing in the water. These rules emphasize the same core principle: the tubs are for soaking, not washing.

Exploring the Tubs

Now for the reward. Most sento offer several tubs with varying temperatures and features. There’s often an “atsuyu” (hot bath), around 42-44°C, which may feel scorching at first but relieves muscle tension like nothing else. Next to it is usually a “nuruyu” (lukewarm bath), comfortable for longer soaks. Then come the fun options. Jet baths (“jetto basu”) with powerful water streams massage your back and legs. The true Osaka specialty, however, is the “denki buro,” or electric bath. This small tub channels low-voltage electric currents between two plates on opposite sides. Sitting between them, your muscles contract and tingle in a pulsating rhythm. It’s an acquired taste; initially, it feels like a gentle taser shock, but regulars swear it soothes deep muscle pain. Trying it, and enduring it, is a rite of passage. Many sento also feature a sauna and, importantly, a “mizuburo” (cold water bath) nearby. The art of the sento wind-down is the cycle: soak in hot water until relaxed, sweat it out in the sauna, then plunge into the icy mizuburo for a refreshing reset before repeating. It’s a full-body reboot.

The Post-Bath Ritual: The Real Wind-Down

The experience doesn’t end when you step out of the water. In fact, some of the most essential parts of the ritual are still to come. This is what transforms the sento from a mere hygiene practice into a foundation of a healthy routine. The shift from the wet, steamy bathing area to the dry calm of the changing room is facilitated by your reliable towel. A subtle but important etiquette is to wring out your small towel and lightly wipe your body before entering the changing room. This prevents water from dripping all over the floor, which is a shared space. It’s a small gesture of consideration that shows you understand the culture.

Once you are thoroughly dry and dressed again, you feel renewed. Your skin tingles, your muscles feel as relaxed as soft noodles, and a deep sense of calm has settled over you. But don’t rush out just yet. The final step happens in the lobby.

The Sento Lobby: Osaka’s Living Room

The lobby or rest area of an Osaka sento is a revered space. It’s where the relaxation truly takes hold. The decor often serves as a perfect time capsule of mid-Showa design: worn vinyl couches, a large massage chair resembling a prop from a sci-fi film, a display case filled with vintage toiletries, and almost always, a big television showing either a Hanshin Tigers baseball game or a sumo tournament. The air is filled with the hum of large fans and the clinking of glass bottles.

This is where you complete the ritual with a post-bath drink. Classic choices sit in old-fashioned glass bottles in a refrigerated case. There’s fruit milk (フルーツ牛乳), a sweet, creamy, slightly fruity drink that tastes like childhood. There’s coffee milk (コーヒー牛乳), its cooler, more refined counterpart. And, naturally, there’s beer. Few pleasures in Osaka compare to a crisp, ice-cold beer after you’ve been boiled, steamed, and plunged. It’s the reward. It’s the full stop at the end of a long sentence.

As you sip your drink, you witness the community in motion. An elderly man holds court, animatedly analyzing the Tigers’ latest game. A mother patiently combs her daughter’s wet hair. Friends chat while planning dinner. This space is a vital “third place” for the neighborhood—not home, not work, but a neutral ground where relationships are built and sustained. It contrasts sharply with a more isolated, individualistic way of life. Here, loneliness is kept at bay through the simple act of showing up. You might not speak to anyone, but by merely sharing the space, you are partaking in the community’s life. Lingering is not just permitted; it’s expected. This is where the true value of the sento routine lies—it creates a cushion of relaxation and social connection between the day’s chaos and the night’s quiet.

Why the Sento is So Osaka

While sento can be found throughout Japan, the experience in Osaka feels distinctly intertwined with the city’s unique cultural DNA. It serves as a perfect microcosm of the Osakan mindset, where the city’s core values of pragmatism, community, and a flamboyant lack of pretense all seamlessly come together.

A Culture of “Gochasou” (Mixing It Up)

Osaka has long been a merchant city, a hub where diverse people, goods, and ideas collide and blend. This spirit of “gochasou,” or mixing everything up, remains vibrant in the sento. The architecture itself often reflects this ethos. While a traditional Tokyo sento might feature a majestic, iconic painting of Mt. Fuji, an Osaka sento is just as likely to showcase an eccentric mosaic of dolphins playing under a European castle or boldly clashing tiles. The playful, anything-goes style rejects solemnity in favor of enjoyment. This lack of pretense is quintessentially Osakan. The city doesn’t take itself too seriously, and neither do its bathhouses. The focus is on feeling good, rather than performing a sacred or aesthetic ritual.

Pragmatism and Community Combined

At its core, Osaka is a practical city. Built on trade and industry, its people prioritize usefulness, efficiency, and value for money. The sento perfectly embodies this mindset. During the post-war boom, when much of the city was rebuilt, many homes and apartments were designed without private baths to save space and expense. The sento became a necessary convenience. However, beyond being just a utility, it evolved into the neighborhood’s heart. This dual role is crucial. Why install a cramped, isolating bathroom at home when, for a modest fee, you can enjoy spacious tubs, a sauna, and a lively social atmosphere all at once? It’s a sensible, resource-efficient solution that also fosters strong community bonds. This is the “jitchokusen” (down-to-earth) spirit of Osaka—a smart answer to a practical issue that also generates social capital as a bonus.

The Sound of Osaka

To truly grasp a city’s soul, listen closely. In the sento, you hear the raw, unfiltered sound of Osaka. Conversations aren’t hushed whispers but are lively, expressive, and often humorous in the distinctive Osaka dialect. People are straightforward and say exactly what they mean. There’s less of the “tatemae” (public facade) and “honne” (true feelings) divide that can confuse outsiders elsewhere in Japan. In the bathhouse, it’s all honne. This openness can be surprising for foreigners used to a more reserved Japanese stereotype, often shaped by Tokyo’s culture. Yet it’s not rudeness; it’s honesty. The loud laughter, unsolicited advice, and playful teasing form part of a social fabric valuing warm, direct interaction over polite distance. The sento acts as the city’s amplifier, where its genuine voice resonates off the tiled walls.

Finding Your Neighborhood Sento and Making It a Habit

So, how do you incorporate this amazing institution into your life? The first step is to explore. Take a walk or bike around your neighborhood, keeping an eye out for that distinctive chimney. Use online maps and search for 「銭湯」. Don’t hesitate to open the door and take a quick look inside. Each sento has its own unique charm. The one three blocks east might be a beautifully preserved Showa-era treasure run by a third-generation owner, complete with creaky wooden lockers and milky water. The one two blocks north could be a recently renovated spot by a young entrepreneur, featuring modern art on the walls, a craft beer selection in the lobby, and a powerful carbonated bath.

Begin by committing to a visit once a week. Maybe Friday evening, to wash away the stress of the workweek. Or Sunday afternoon, as a leisurely, restorative treat. Before long, it will become a natural part of your routine. You’ll start recognizing the regulars—the elderly man who always takes the same spot in the electric bath, or the group of friends who gather every Wednesday. They’ll start noticing you, too. A nod will evolve into a “hello,” and eventually into a conversation. This is how connections are built.

Don’t let fear hold you back. Concerned about your tattoos? Although historically linked to the yakuza, attitudes are shifting, especially in a cosmopolitan city like Osaka. Many local sento are fine with tattoos, but it’s always best to check their policy beforehand if you have significant ink. Worried you’ll break the rules? You might. But a gentle correction from a regular is not a lecture; it’s an invitation. It means they see you not as a tourist to be dismissed, but as a potential community member worth guiding. The aim isn’t to perfectly imitate “being Japanese.” The aim is to participate, be present, and let the warm water work its magic.

The Future of Sento and Its Place in Modern Osaka

Sento are undeniably becoming a dying breed across Japan. As modern apartments with private baths become standard, the original purpose of public bathhouses has diminished. Each year, more old sento close their doors, their iconic chimneys falling silent. Yet in Osaka, a city known for its resilience and creativity, the story continues. A new generation is appreciating sento not just as bathing spots but as vital community spaces. Young owners are inheriting family businesses, renovating facilities with a modern touch while carefully preserving the nostalgic atmosphere. They’re hosting events such as live music, yoga classes, and even pop-up bars in their lobbies. They collaborate with local artists and designers, reimagining the sento as a cool, retro, and authentic experience—a deliberate choice in an era of digital isolation. This revival movement proves that the sento is not a relic relegated to history. It remains an adaptable, living tradition essential to Osaka’s identity.

From a Bathhouse to a Feeling of Home

Living in Osaka means being enveloped by a constant, thrilling, and sometimes overwhelming flow of energy. The sento is the city’s hidden refuge, a place to step away from the rush for an hour or two and simply exist. It’s much more than just a bath. It serves as an affordable, effective remedy for the aches and pains of a long day. It’s a sure antidote to loneliness. It offers a sensory journey that connects you to the history and the vibrant, living reality of your neighborhood. Emerging from a sento onto the quiet streets at night, your body warm and your mind at ease, you view the familiar city lights with fresh eyes. The world feels a little softer, a little kinder. You realize you’re no longer just an anonymous resident in a vast city. You’re the person who nods to the guy from the electric bath, the person who knows where to find the best post-soak coffee milk, the person who is part of the rhythm. The first time you push through that noren curtain, you’re a stranger. By the tenth time, you’re a regular. And that feeling—that simple, warm sense of belonging—is how a foreign city eventually begins to feel like home.