There’s a rhythm to Osaka that you won’t find in a travel guide. It’s a pulse that beats not in the gleaming shopping malls of Umeda or the theatrical neon canyons of Dotonbori, but in the city’s rough-around-the-edges, fiercely local neighborhoods. Just one stop north of the central hubbub on the Hankyu line lies Juso, a district that feels like a living time capsule, a gritty, smoke-filled, heart-on-its-sleeve testament to a bygone era. This isn’t a place of curated aesthetics or polished photo opportunities. Juso is raw, it’s real, and it is the undisputed kingdom of ‘senbero’. The word itself is a beautiful piece of Japanese slang, a portmanteau of ‘sen’ (one thousand) and ‘berobero’ (drunk or tipsy). It’s the art, the challenge, and the promise of achieving a pleasant buzz for a single 1,000-yen note, which is roughly ten US dollars. But senbero is more than just a cheap night out; it’s a cultural institution, a social ritual, and your most direct path into the warm, unpretentious soul of working-class Osaka. Forget your reservations and your quiet, contemplative bars. Prepare to dive headfirst into a labyrinth of clatter and cheer, where the drinks are strong, the food is fried, and the welcome is as genuine as the faded linoleum on the floor.

If you’re looking for another authentic local experience beyond Juso’s drinking culture, you can discover incredible Turkish cuisine in Osaka’s nearby Shonai neighborhood.

The Neon-Soaked Labyrinth: First Impressions of Juso

Stepping off the Hankyu train at Juso Station is a complete sensory experience. The very air feels different—thick with the intoxicating aroma of sizzling oil, sweet yakitori smoke, stale cigarette haze, and a subtle metallic trace from the nearby train tracks. The platform buzzes with a steady stream of people, representing a cross-section of Osaka life, from tired salarymen loosening their ties to elderly women carrying shopping bags and students commuting to and from school. However, the true Juso reveals itself as soon as you pass through the ticket gates, especially on the west side. You are instantly immersed in a chaotic symphony of sound and light. Pachinko parlors clang and chime with a deafening, hypnotic beat, their gaudy lights flashing in a relentless, frenetic dance. Narrow, covered shopping arcades, or ‘shotengai’, extend like arteries from the station, their ceilings a web of wires and aged fluorescent tubes that cast a perpetual twilight glow. Weather-worn signs with peeling paint and buzzing neon kanji vie for your attention, advertising everything from cheap noodle shops and discount pharmacies to discreet karaoke bars and, naturally, the countless izakayas that form the heartbeat of the neighborhood.

This is not the manicured Japan of popular fantasy. It’s gloriously and unapologetically cluttered. Bicycles lean against storefronts, plastic crates filled with beer bottles create makeshift walls, and the ground is a patchwork of worn tiles and stained concrete. Yet amid this disorder, there is an unmistakable energy—a pulse of life that feels far more genuine than the polished tourist areas. You can sense the history in the weathered wooden counters and the generations of laughter embedded in the walls. Juso moves at its own pace, driven by the rhythms of the daily commute and the universal desire to relax. It beckons you not to watch from the sidelines, but to join in—to become part of its noisy, vibrant, and utterly captivating flow.

Decoding the Senbero Code: More Than Just a Cheap Drink

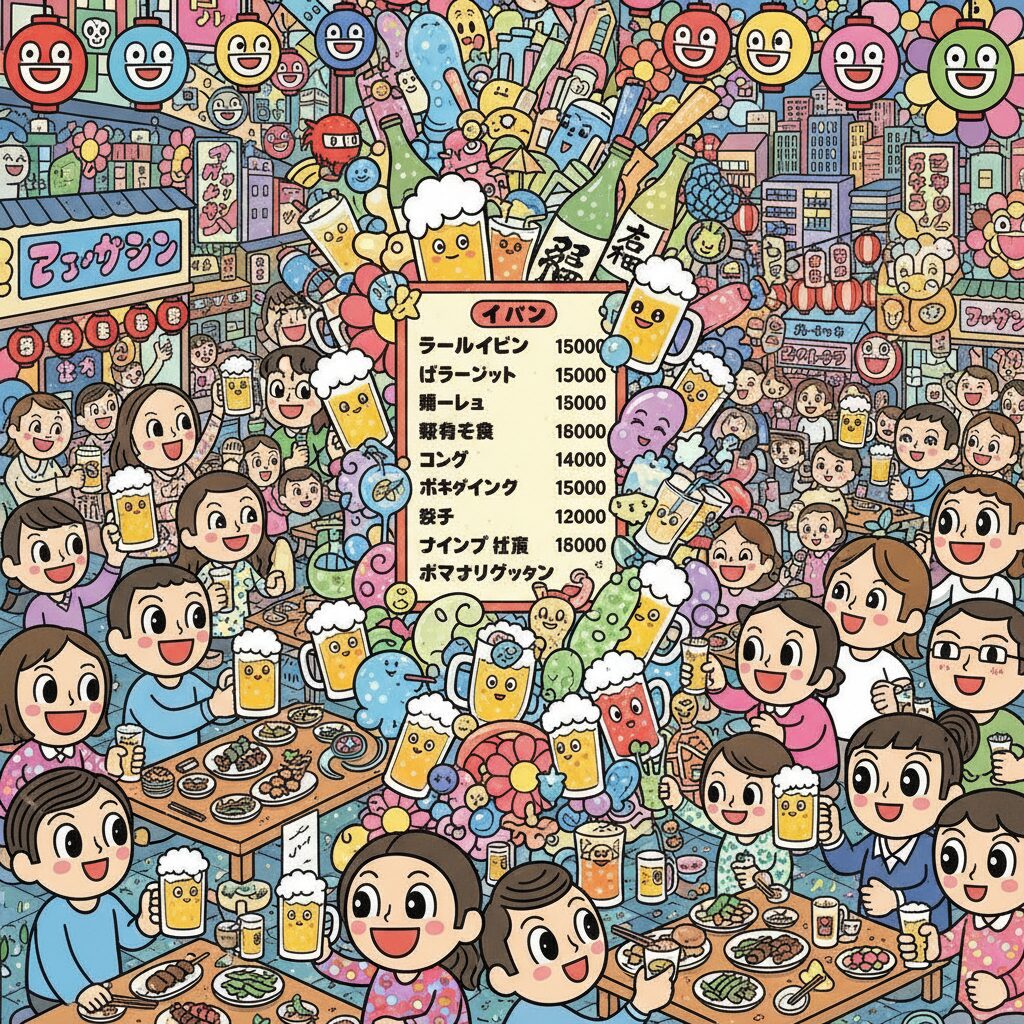

To understand Juso, you must first grasp the philosophy of senbero. On the surface, it’s a straightforward concept: 1,000 yen for a good time. Most places offering a ‘senbero set’ serve a combination of drinks and one or two small dishes for this price. Typically, you might get two or three draft beers or chu-hais paired with a plate of ‘doteyaki’ (slow-cooked beef tendon stew) or a couple of ‘kushikatsu’ (deep-fried skewers). While it’s an incredible value, its significance goes far beyond economics. Senbero acts as a social lubricant, a democratic institution where blue-collar workers, office clerks, and the occasional adventurous student stand side-by-side, united by the simple joy of a cold drink and a hot snack after a long day. It’s a ritual that cultivates a unique form of fleeting community. You may only share a few square feet of counter space with a stranger for twenty minutes, but in that brief time, a bond is created through a shared laugh or a nod of appreciation for an especially tasty skewer.

This tradition traces back to the post-war economic boom, when 立ち飲み (tachinomi), or standing bars, became popular stops for the growing workforce. They were built for speed and efficiency—a place to grab a quick drink and snack before catching the train home. There’s no pretense, no frills, and no pressure to stay long. In Juso, this spirit thrives. The senbero culture stands in stark contrast to fine dining. It emphasizes immediacy, accessibility, and the delight of simple, well-made food and drink. It reminds us that the best experiences are often not the most expensive, but the most authentic. It embodies a rejection of formality, a celebration of the everyday, and a deep appreciation for the simple act of gathering to share a brief moment of respite from the demands of the outside world.

A Symphony of Sizzle and Smoke: The Tachinomi Experience

The quintessential Juso izakaya is a tachinomi, a standing bar that forms the vibrant heart of the neighborhood’s social life. Forget spacious seating and personal space; a tachinomi is all about cozy, communal living. The interiors are often delightfully cramped, with a narrow space dominated by a long wooden or stainless-steel counter. Behind it, the master, or ‘taisho,’ expertly manages his domain—a grill, a deep fryer, and a bubbling pot of stew—with practiced, almost balletic precision. The air is thick with a tapestry of aromas: the sweet, caramelized scent of soy-based marinades sizzling on the grill, the sharp tang of pickled ginger, the comforting fragrance of simmering dashi broth, and the ever-present haze of cigarette smoke clinging to everything. Space is limited, so you’ll find yourself standing elbow-to-elbow with fellow patrons—a closeness that might feel awkward elsewhere but here feels natural, even essential. It breaks down barriers and fosters conversation.

The soundscape is equally rich. There’s the constant sizzle and pop from the kitchen, the rhythmic clatter of plates and utensils, the satisfying ‘thwack’ of a beer bottle opening, and a low, steady hum of conversation. Laughter erupts from one corner, a gruff but friendly order is shouted from another, and a television mounted in the corner might be broadcasting a baseball game or variety show, adding another layer to the audio collage. This environment isn’t for the faint-hearted, but for those who embrace it, it is deeply rewarding. It’s a place where you’re not just a customer but a temporary member of a club, partaking in a nightly ritual that has played out similarly for decades. The absence of chairs is deliberate; it promotes a higher turnover of customers and keeps the atmosphere dynamic and fluid. You come, you eat, you drink, you pay, and then you move on, making way for the next person to join the symphony.

Reading the Room: Tachinomi Etiquette for First-Timers

For first-timers, a bustling tachinomi can be intimidating, but a few simple tips will help you navigate the scene like a local. First and foremost, cash is king. Many of these traditional spots don’t accept credit cards. The system usually works ‘cash on delivery’—you place your money in a small tray on the counter, and the staff deducts the correct amount as you order, returning any change. This keeps things quick and simple. Second, mind your space. These bars are crowded, so keep your belongings compact and avoid spreading out. When you’re finished, don’t linger too long, especially if others are waiting to get in. The unwritten rule is to enjoy your time but be aware that others are waiting their turn.

Ordering can be the biggest challenge since menus are often handwritten in Japanese on strips of paper pasted to the wall. Don’t let this discourage you. A bit of courage and a friendly attitude go a long way. The easiest way is to watch what others are eating and simply point. A confident ‘Kore, kudasai!’ (‘This one, please!’) with a smile works wonders. It also helps to know the names of a few key dishes and drinks. For beer, ask for ‘Nama biru’ (draft beer). For a highball, simply say ‘haiboru.’ The staff and even other customers are usually very welcoming to foreigners who make an effort. They appreciate your interest in their culture and are often happy to help. A simple ‘Oishii!’ (‘Delicious!’) after you eat will earn warm smiles and might even spark a conversation. The key is to be open, observant, and respectful of the space’s unwritten rules.

Navigating the Culinary Crossroads: What to Eat in Juso

While the drinks are inexpensive and abundant, it is the food that truly defines the Juso senbero experience. This is not sophisticated cuisine; rather, it is hearty, flavorful, and deeply comforting fare crafted to perfectly accompany a cold beer or a sharp highball. The menus celebrate classic Osaka comfort food, with each dish refined through years of repetition. As you stroll through the shotengai, your senses become your best guide, drawing you toward the most enticing aromas and the busiest counters—a reliable sign of quality.

The Gospel of Kushikatsu: Osaka’s Golden Skewers

If Osaka has a quintessential bar snack, it is kushikatsu. These skewers feature a variety of ingredients—meat, seafood, vegetables—coated in a light panko breadcrumb and deep-fried to a perfect golden crisp. In Juso, counters are lined with trays of pre-skewered items, allowing you to select exactly what you desire. The variety is dizzying. Classic options include pork (‘buta’), beef (‘gyu’), quail eggs (‘uzura’), and lotus root (‘renkon’). More adventurous choices might include chicken gizzards (‘sunagimo’), cheese (‘chizu’), and even fried ginger (‘shoga’). After you make your selection, the taisho fries them fresh, serving them piping hot. A crucial part of the kushikatsu ritual is the shared pot of thin, dark dipping sauce. Here lies the cardinal rule, posted in every shop: NO DOUBLE DIPPING. You dip your skewer once, and only once, before taking your first bite. This rule is based on public hygiene and deeply rooted tradition. If you need more sauce, you use the provided slice of raw cabbage to scoop it onto your plate. The combination of the crispy, savory skewer, the tangy sauce, and the crisp cabbage creates a perfect trifecta of textures and flavors.

Doteyaki Dreams: The Soul-Warming Simmer

Simmering in a large, shallow pot at the corner of nearly every bar counter is a rich, dark stew called ‘doteyaki’. This is a beloved Osakan comfort food, a slow-cooked blend of beef sinew (‘suji’), konnyaku jelly, and sometimes tofu, stewed in a mixture of sweet miso, soy sauce, and mirin. The long, slow cooking makes the tough beef sinew incredibly tender, melting in your mouth with a rich, savory-sweet flavor that is deeply addictive. It is typically served in a small bowl, garnished generously with chopped green onions. The depth of flavor is profound, showcasing the power of simple ingredients and time. Doteyaki is an ideal dish to start your evening. It coats your stomach, warms your soul, and pairs perfectly with a crisp, cold draft beer, whose bitterness cuts through the stew’s richness. A humble dish born of necessity and the desire to use every part of the animal, it has been elevated to an art form in Juso’s izakayas.

From the Grill: Yakitori and Beyond

The irresistible scent of charcoal smoke will lead you to a bar specializing in grilled items. ‘Yakitori’, or grilled chicken skewers, is a staple, but Juso’s offerings often go far beyond. You can choose from various parts of the chicken, each with its own distinct texture and flavor. ‘Momo’ (thigh) is juicy and tender, ‘kawa’ (skin) is grilled to crispy, salty perfection, ‘tsukune’ (minced chicken meatballs) are savory and soft, and ‘nankotsu’ (cartilage) delivers a delightful crunch. Beyond chicken, you’ll find skewers of pork belly, green peppers, shiitake mushrooms, and leeks. A key part of Osaka’s culinary identity is ‘horumon’, or offal, and many places grill various cuts of intestine and organ meats, prized for their deep, rich flavor by locals. Skewers are usually seasoned with either simple salt (‘shio’) or a sweet and savory soy-based glaze (‘tare’). Watching the taisho expertly fan the charcoal, turn the skewers, and brush on the seasoning is a form of culinary theater. The smoky, slightly charred flavor from the grill is elemental and utterly satisfying, making an ideal companion to a glass of shochu on the rocks.

The Juso Drink Menu: An Unpretentious Guide

The beverage choices at a Juso senbero spot are refreshingly simple and designed for extended drinking sessions. You won’t find craft cocktails or lengthy wine lists here. Instead, the emphasis is on cold, refreshing, and budget-friendly drinks that quench your thirst and pair well with the salty, savory food. The undisputed favorite is ‘nama biru,’ or draft beer, typically served in a frosty, heavy glass mug. Major Japanese brands like Asahi, Kirin, and Sapporo are standard offerings. Another hugely popular option is the ‘haiboru,’ or highball, a straightforward yet brilliant mix of Japanese whisky (usually a basic brand like Suntory Kaku) and super-carbonated soda water, served in a tall glass filled with ice. It’s crisp, dry, and incredibly refreshing.

Then there’s the world of ‘chu-hai,’ short for ‘shochu highball.’ This versatile drink is made with shochu (a Japanese distilled spirit), soda, and usually a fruit flavoring. Classic flavors include lemon, grapefruit, and ume (plum), though a wide variety is available. They tend to be light, easy to drink, and surprisingly potent. For traditionalists, sake and shochu are always options. Sake is often a simple, no-frills ‘futsushu’ (table sake), served hot (‘atsukan’) or cold (‘hiya’). Shochu can be enjoyed neat, on the rocks (‘rokku’), or mixed with water (‘mizuwari’) or hot water (‘oyuwari’). The prices are the main draw. A draft beer or highball might cost as little as 300 or 400 yen, making it easy to see how a 1,000-yen senbero budget can stretch into a very enjoyable evening.

The Human Element: Portraits from Behind the Counter

What truly defines the Juso experience, beyond the food and drink, are the people. These establishments are often family-run, handed down through generations, with the owners as integral to the atmosphere as the decor. Behind the counter, you might encounter a stoic, elderly taisho, his face etched with the stories of his long life, who communicates more with a nod and a grunt than with words. He moves with an economy of motion honed by decades of practice, his hands precisely knowing how much salt to sprinkle on a skewer or how long to leave a cutlet in the fryer. Though he may seem intimidating at first, a polite ‘gochisosama deshita’ (‘thank you for the meal’) upon leaving often elicits a rare, genuine smile that brightens his entire face.

In another bar, the proprietor could be a cheerful, talkative ‘obachan’ (auntie figure) who treats every customer like one of her own children. She keeps the conversation lively, chiding her regulars, asking about their families, and ensuring everyone’s glass is full. She is the heart of the community, the keeper of stories, and the reason many return night after night. And then there are the customers themselves: weary salarymen in their suits, their shoulders relaxing as they take the first sip of beer, their chatter a mix of office gossip and grumbles about their bosses; the old men who have been drinking at the same spot on the same stool for thirty years, quietly reading a newspaper or watching the baseball game; the young couples on a budget-friendly, cheerful date, sharing skewers and laughing. By standing among them, you stop being a tourist and, for a short time, become part of the fabric of daily life in Osaka. This is Juso’s true gift: a genuine connection to the people and culture of this remarkable city.

A Practical Blueprint for Your Juso Adventure

Equipping yourself with some practical knowledge will ensure your introduction to Juso’s senbero scene is smooth and thoroughly enjoyable. The secret is to approach the experience with an open heart and a sense of adventure.

Getting There and Getting Around

One of Juso’s greatest strengths is its accessibility. Situated on the Hankyu Railway line, it is just one express stop from the major transit hub of Hankyu Umeda Station. The trip takes only three to five minutes, making it an incredibly convenient side excursion from central Osaka. Upon arriving at Juso Station, the best way to explore is on foot. The liveliest area, filled with izakayas and tachinomi bars, lies immediately west of the station. The covered shotengai arcades form a maze best navigated by wandering and following your instincts. There’s no need for a map; getting slightly lost is part of the charm. Each narrow alley seems to hide another tiny bar or secret eatery waiting to be found.

Timing is Everything

Juso truly comes alive after dark. While some shops operate during the day, the real excitement starts around 5:00 PM. This is when the red lanterns (‘akachochin’) outside the izakayas are lit, casting a warm, welcoming glow over the dimming streets. Salarymen finish work and pour out of the station, and the bars swiftly fill with the lively hum of after-work conversations. Weeknights provide a more genuine, local atmosphere, where you’ll sit alongside regular patrons. In contrast, Friday and Saturday nights are busier and more festive. If you plan to bar-hop (‘hashigo-zake’ in Japanese), weeknights offer a better chance of snagging a spot at the counters of multiple bars.

Cash, Comfort, and Courage

Three essentials guarantee a successful night out in Juso. First, bring cash. Many small, traditional establishments accept only cash. Having a mix of 1,000-yen bills and coins will simplify transactions, especially with the ‘cash on delivery’ system. Second, wear comfortable shoes. You’ll spend a lot of time standing, both in tachinomi bars and while walking between them. Comfort is crucial for fully enjoying your evening. Finally, carry a bit of courage. It can be intimidating to push aside the ‘noren’ curtain of a busy, noisy bar where you might be the only foreigner. But take a deep breath and step inside. The reward is an experience of unmatched authenticity. A smile and a willingness to try are the only universal languages you need. Osaka’s people are renowned for their warmth and friendliness, and your small effort will be met with great kindness and hospitality.

The Enduring Spirit of Showa-Era Osaka

A night in Juso is more than a culinary adventure; it’s a journey into the past. In a country often caught in a continuous cycle of reinvention, Juso remains wonderfully and stubbornly frozen in the Showa era (1926-1989). It serves as a living museum of a time when Japan was rebuilding, neighborhood bonds were forged in local bars, and simple pleasures were deeply cherished. The peeling paint, flickering neon, and worn wooden counters aren’t part of a retro theme—they are authentic relics of a past that still lives on.

This is the side of Osaka that exists beyond glossy brochures and tourist routes. It’s a place with soul, where character is etched into every street corner. It’s loud, a bit gritty, and filled with a genuine, heartfelt hospitality that is becoming increasingly rare. Spending an evening hopping between Juso’s tachinomi is to see the city unguarded, share drinks with its people, and savor the flavors that have sustained them for generations. So leave your expectations behind, bring a hearty appetite and an open heart, and let the warm glow of the red lanterns lead you into the timeless, welcoming spirit of Osaka’s senbero soul.