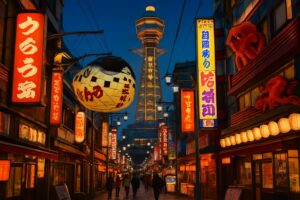

Step off the train at Dobutsuen-mae Station, and the air changes. It’s not just the temperature or the humidity; it’s the very texture of the atmosphere. You’ve arrived in Shinsekai, Osaka’s “New World,” a neighborhood paradoxically frozen in time, a living museum of Showa-era dreams and grit. This isn’t the polished, futuristic Japan of glossy travel brochures. This is a place with a soul, a little rough around the edges, fiercely proud, and pulsating with a raw, electric energy. At its heart, fueling its boisterous spirit, is a sound and a smell that define Osaka for so many: the sizzle and savory aroma of kushikatsu. Forget what you think you know about fried food. Here, in the shadow of the iconic Tsutenkaku Tower, the simple act of deep-frying skewered morsels is elevated to an art form, a ritual, a way of life. It’s the culinary anchor of a community, a taste of history served on a bamboo stick. To walk these streets, lit by the gaudy glow of giant fugu lanterns and the benevolent smile of the Billiken statues, is to prepare for a journey into the very core of Osakan identity. This is a pilgrimage for food lovers, a quest not just for a meal, but for an experience that is unapologetically local, profoundly delicious, and utterly unforgettable. Welcome to Shinsekai, the undisputed kingdom of kushikatsu.

For a deeper dive into the area’s rich history, from ancient temples to modern attractions, explore our guide to exploring Tennoji.

The Echoes of a Forgotten Future

To truly appreciate the kushikatsu of Shinsekai, you first need to understand the district itself. Its name, meaning “New World,” reflects a bold vision. Established in 1912, Shinsekai was built on the site of the 1903 National Industrial Exposition, an event that exhibited Japan’s rapid modernization to the world. The area was designed as a futuristic utopia, a playground for the public. The northern section drew inspiration from Paris, featuring the original Tsutenkaku Tower, a steel structure intended to evoke both the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe. The southern section took cues from Coney Island, with an amusement park named Luna Park. For a fleeting, luminous period, Shinsekai was the vibrant, forward-looking heart of Osaka, a symbol of progress and popular entertainment.

However, history, as is often the case, unfolded differently. Luna Park eventually closed, the tower was dismantled for its steel during World War II, and the post-war economic boom largely overlooked Shinsekai. The area froze in time, with its majestic boulevards and narrow lanes narrating a tale of past grandeur. It became known as a district for laborers, offering inexpensive entertainment, and standing as a bastion of a grittier, more authentic Osaka. It was in this distinctly working-class environment that kushikatsu originated. The dish mirrors its surroundings: quick, affordable, satisfying, and delicious. It was food for the common people, made to be eaten standing at a counter and washed down with a cold beer after a hard day’s work. The original kushikatsu stands were simple, serving skewered beef and vegetables dipped in batter and fried to a crispy golden brown. It was nourishment, but also a modest, accessible treat. The communal pot of dipping sauce became a symbol of the neighborhood’s unpretentious, shared spirit. This history is infused in every bite you savor today. Eating kushikatsu in Shinsekai means tasting not just fried food but the resilience, pragmatism, and enduring spirit of Osaka’s working class.

The Art of the Skewer

At its essence, kushikatsu, also called kushiage, appears deceptively simple. “Kushi” means bamboo skewers, and “katsu” is derived from “katsuretsu,” the Japanese version of “cutlet.” Various ingredients—meat, seafood, vegetables, cheese, and even desserts—are threaded onto skewers, dipped in a light batter made of flour and egg, coated with delicate panko breadcrumbs, and then deep-fried until perfectly golden brown. The end result is a textural marvel: an explosively crisp crust that gives way to a tender, juicy interior. The secret lies in the details. The batter is generally thinner and lighter than Western-style fried coatings, and the panko is ground to a specific fineness to maximize crunch while minimizing oil absorption. Each skewer is fried to order and served piping hot, inviting immediate enjoyment.

However, the skewer is only part of the story. The other essential element is the sauce. It is not the thick, sweet tonkatsu sauce commonly found elsewhere. The kushikatsu sauce of Shinsekai is thinner, darker, and more savory, featuring a tangy Worcestershire-like base often combined with fruit and vegetable purées to provide subtle sweetness and complexity. It is crafted to cut through the richness of the fried coating, complementing the ingredient inside without overpowering it. This sauce is the heart of the establishment, its recipe a closely guarded secret passed down through generations. It rests in a communal stainless steel container on the counter, silently welcoming all who gather.

The Sacred Rule: No Double-Dipping

Before enjoying your first skewer, you must learn the single, unbreakable rule of kushikatsu culture: never dip a skewer into the communal sauce pot more than once. This rule, prominently displayed on signs in every restaurant, transcends language barriers as an act of hygiene rooted in the shared nature of the sauce. You dip your skewer once and only once, fresh from the fryer and untouched by your mouth. This is the law. What if you misjudge and need more sauce halfway through a large piece of lotus root? This is where the humble cabbage comes in. A bowl of raw, crisp cabbage wedges is always provided free of charge. It serves two purposes: first, as a palate cleanser between rich, fried skewers, and second, as a makeshift spoon. You can use a clean cabbage leaf to scoop sauce from the pot and drizzle it onto your kushikatsu, allowing you to honor the sacred rule while achieving your ideal sauce-to-skewer balance. Observing this etiquette shows respect and signals your appreciation for the local culture.

A Universe on a Stick

One of the greatest pleasures of eating kushikatsu in Shinsekai is the astonishing variety. The menu at a typical restaurant can feel endless—a catalog of everything delicious that can be skewered and fried. For beginners, it’s best to start with the classics. Gyu-katsu (beef) is the quintessential skewer, the one that started it all. Buta-bara (pork belly) offers a richer, more indulgent bite. Tori (chicken) is a lean, familiar favorite. From there, the world expands. Vegetables are transformed by the fryer. Tamanegi (onion) becomes sweet and meltingly soft. Renkon (lotus root) retains its uniquely crunchy texture. Nasu (eggplant) absorbs flavors and turns remarkably creamy. Asparagus, shiitake mushrooms, shishito peppers, and sweet pumpkin chunks are all common options.

The sea is well represented as well. Ebi (shrimp) is a classic, its natural sweetness enhanced by the crisp coating. Hotate (scallops) are plump and juicy, while ika (squid) offers a pleasant chew. Kisu (whiting) is a light, flaky fish that pairs beautifully with the savory sauce. Adventurous eaters can try quail eggs (uzura no tamago), little pockets of creamy yolk encased in a crispy shell. Then come the more inventive creations: cheese wrapped in thin pork slices or fried alone becomes a molten, indulgent treat. Mochi (rice cake) turns delightfully gooey and chewy inside. Red ginger (beni shoga), a staple pickle in Osaka, transforms into a zesty, piquant burst of flavor when fried. Some places even offer dessert skewers—fried bananas or ice cream tempura—for a sweet, surprising finish. Ordering is part of the fun: you can choose individual skewers or go for a “moriawase,” a chef’s assortment set, which is an excellent way for beginners to sample a wide variety of offerings.

The Neon Labyrinth: Finding Your Fryer

Strolling along Shinsekai’s main streets, you’ll be overwhelmed with choices. Brightly illuminated restaurants boasting enormous, three-dimensional signs and long tourist lines stand side-by-side with quieter, more modest establishments tucked away in side alleys. Each offers a slightly different experience, a unique glimpse into the world of kushikatsu.

The Guardians of the Flame

These are the traditional, legendary shops, some operating for decades. Often small, cramped, and richly atmospheric, you might find yourself squeezed onto a stool at a worn wooden counter that has witnessed countless meals and conversations. The air is thick with the scent of frying oil and the gentle hum of local chatter. The master, or “taisho,” exudes quiet authority, his movements behind the fryer precise and economical from years of experience. The menu is often limited, focusing on classic dishes perfected over time. The service is efficient, perhaps a bit brusque, but that’s part of the charm. This isn’t a place to linger; it’s meant for eating, drinking, and soaking in the pure essence of Shinsekai. Here, you’re not just a customer; you become a temporary participant in a long-standing local tradition. You might find yourself dining alongside salarymen unwinding after work or an elderly couple who have frequented the same spot weekly for thirty years. These places hold the very history of kushikatsu within their walls.

The Bright Lights of the Big City

At the other end of the spectrum are the large, well-known kushikatsu chains that have become iconic in Shinsekai. They’re impossible to miss. Their storefronts are decorated with huge statues of mascots, often an angry-looking chef, a clear warning against double-dipping. These restaurants are popular for good reason. They’re accessible, often provide English menus, and deliver a consistent, high-quality product. The atmosphere is lively and noisy, filled with tourists and families enjoying a fun, affordable meal. Though some purists may scoff, these larger venues play a crucial role in introducing kushikatsu to a broader audience. They’re an excellent starting point for first-timers, offering a comfortable and easy introduction to the customs and flavors of this Osakan specialty. Their extensive menus frequently feature creative and modern kushikatsu alongside traditional favorites, ensuring something for everyone.

Down the Rabbit Hole: Janjan Yokocho Alley

For a truly immersive experience, explore Janjan Yokocho. This narrow, covered shopping arcade—named after the shamisen’s strumming sound once used to attract customers—is the vibrant heart of old Shinsekai. Here, kushikatsu restaurants are even smaller and more intimate. You’ll also find stand-up sushi bars, budget-friendly izakayas, and storefronts for shogi (Japanese chess) and Go, where elderly men concentrate quietly. Walking through this alley is like stepping back in time. The air is thick with the aromas of grilling meat, frying batter, and cheap beer. The noise is a constant, friendly cacophony. Scoring a seat at one of the tiny kushikatsu counters feels like finding a secret. You’ll be elbow-to-elbow with locals, sharing a moment of delicious, unpretentious camaraderie. This is also where you might try another Shinsekai specialty, doteyaki—a rich, slowly simmered stew of beef sinew and konjac jelly in a sweet-savory miso broth. It’s the perfect pairing for a plate of crispy kushikatsu, a flavorful one-two punch of classic Osaka tastes.

Beyond the Fryer: Soaking in Shinsekai

While kushikatsu is undoubtedly the highlight, the Shinsekai neighborhood itself is a destination worth exploring. You could easily spend hours wandering its streets, soaking in the delightfully kitsch and exaggerated scenery. The architecture presents a chaotic yet charming blend of pre-war nostalgia and post-war practicality. Every storefront seems to vie for attention with giant, three-dimensional models of their goods, ranging from enormous fugu lanterns to gigantic crabs and a larger-than-life chef. It’s a photographer’s paradise, a vibrant feast of color and character.

The Sentinel of Naniwa: Tsutenkaku Tower

The iconic landmark of the area is Tsutenkaku Tower, the “Tower Reaching Heaven.” The current structure, rebuilt in 1956, stands as a proud emblem of Osaka’s post-war recovery. Riding the elevator to its observation decks provides a sweeping view of the city, putting the street-level chaos into perspective. But the tower is more than just a lookout. It houses Billiken, the “God of Things as They Ought to Be.” This grinning, mischievous statue was created by an American artist and brought to Japan as part of the original Luna Park. Billiken quickly became a sensation and the unofficial mascot of Shinsekai. It’s said that rubbing the soles of his feet brings good luck, a ritual eagerly performed by countless visitors. His smiling face is everywhere in the neighborhood—on souvenirs, signs, and even manhole covers—offering a constant, cheerful presence watching over the area.

Games and Spectacles

Shinsekai also maintains its identity as an entertainment district. Vintage movie theaters screen classic films, while retro arcades are alive with the sounds of old-school video games and pachinko machines. The neighborhood is also home to Spa World, a vast bathhouse complex featuring themed hot springs from around the world, providing a different kind of urban escape. The blend of old and new, tradition and entertainment, gives Shinsekai its distinctive and captivating character. It’s a place that doesn’t take itself too seriously, inviting you to relax, have fun, and enjoy some incredibly delicious food.

A Practical Guide to Your Kushikatsu Pilgrimage

Exploring Shinsekai is fairly easy. The neighborhood is conveniently reachable from multiple train stations. JR Shin-Imamiya Station on the Osaka Loop Line, Dobutsuen-mae Station on the Midosuji and Sakaisuji subway lines, and Ebisucho Station on the Sakaisuji line all place you within a short walk of the main attractions. The best time to visit Shinsekai is in the evening. As night falls, neon signs light up, bathing the streets in a vibrant, cinematic glow. Restaurants fill quickly, and the area buzzes with lively energy. Although it can get crowded, especially on weekends, this bustling atmosphere is a key part of its charm. Most kushikatsu restaurants are quite affordable, with skewers priced between 100 and 300 yen each. A satisfying meal with a drink often costs less than 2,000 yen, making it one of Osaka’s best value dining options. Expect a casual setting, as these are not upscale establishments. Cash remains the preferred payment method in many smaller, older shops, so it’s a good idea to carry some. Above all, bring an open mind and a hearty appetite.

The Lingering Taste of Authenticity

As you finally push away from the counter, full and content, the warmth of the food and the vibrant atmosphere linger. Leaving Shinsekai feels like awakening from a strange and wonderful dream. The flavors of the savory sauce, the crunch of the panko, the sweetness of a perfectly fried onion—these tastes remain with you. But more than that, it’s the essence of the place that lasts. Shinsekai stands as proof that a place doesn’t need to be polished or new to be beautiful. Its charm is found in its imperfections, its resistance to change, and its lively, welcoming spirit. It’s a neighborhood that proudly displays its history, a place where the past isn’t just recalled but is actively, vividly alive. A meal of kushikatsu here is a journey to the heart of Osaka, a city that values good food, good company, and a good time above all. It’s a simple pleasure, a taste of a world that once was and, fortunately, still is. And as you walk away, the neon glow of Tsutenkaku fading behind you, you carry with you a piece of its irrepressible soul, a memory fried in gold.