Coming from Tokyo, I thought I had the public bath thing figured out. A sentō, a public bathhouse, was a place you went for a quiet soak, a solitary ritual in a city that never stops moving. You go in, you wash, you soak, you leave. Simple. It was a transaction of cleanliness and tranquility. Then I moved to Osaka, and I realized I didn’t know a thing. Here, the sentō isn’t just a place to get clean. It’s the neighborhood’s living room, its confession booth, its comedy club, and its community center, all rolled into one steamy, tile-lined package. The quiet I was used to was replaced by a lively hum of conversation, the solitary soak punctuated by the laughter of strangers who, by the end of the evening, didn’t feel like strangers at all.

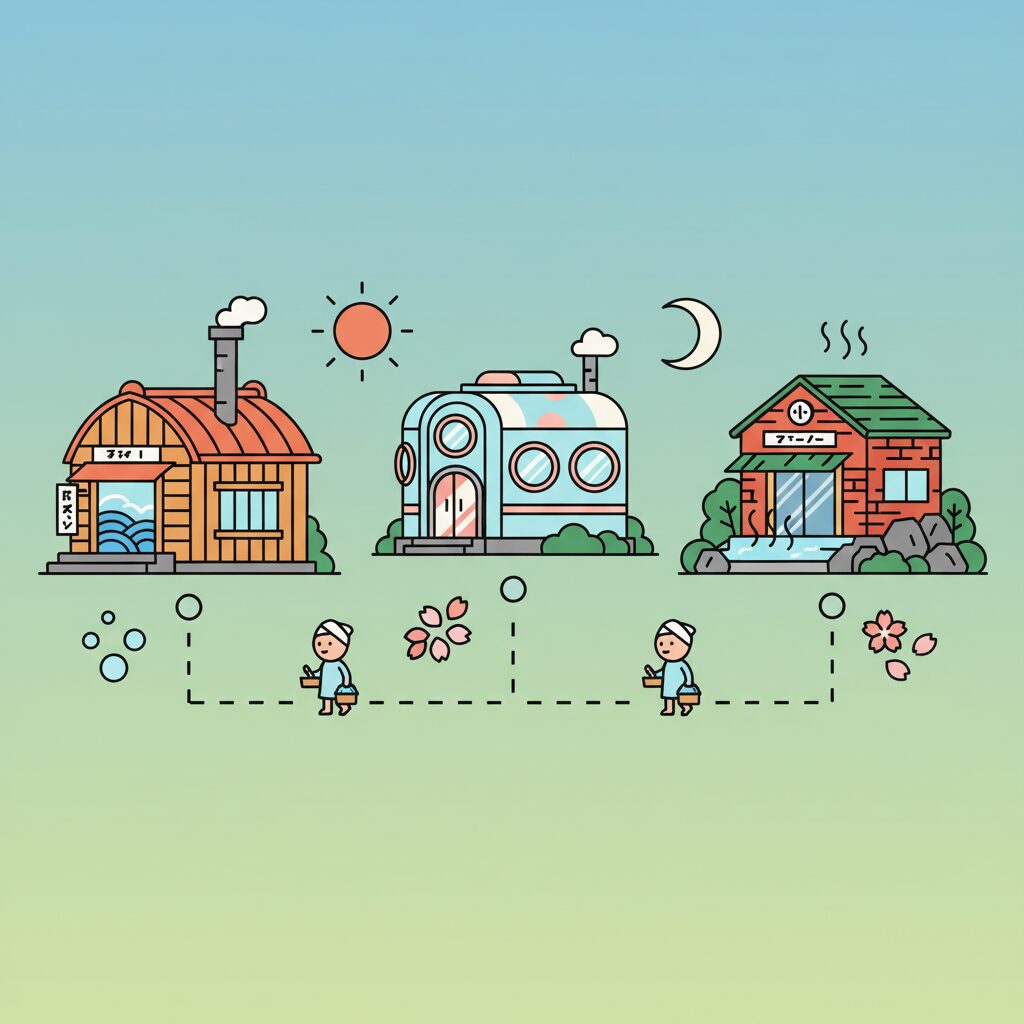

This is a guide to what I call ‘sentō-hopping,’ but let’s be clear: this isn’t a race to tick off the most bathhouses from a list. It’s a method of urban exploration. It’s a passport into the heart of Osaka’s fiercely local, unapologetically vibrant neighborhoods. Each sentō, with its unique quirks, its specific brand of hot water, and its cast of regular characters, offers a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the city’s soul. Forget the guidebooks that point you to castles and giant crabs. The real story of Osaka is whispered over the sound of running water in a bathhouse in Tennoji, debated loudly in front of a blaring TV in a changing room in Nishinari, and shared with a knowing nod in a retro lobby in Nakazakicho. This is your key to understanding the unspoken rules, the deep-seated mindset, and the everyday rhythm of a city that moves to its own beat. This is how you learn to see, and feel, the real Osaka.

For a different kind of Osaka adventure, consider planning a visit to Universal Studios Japan to experience its thrilling rides and immersive worlds.

The Sentō as a Social Hub: Why Public Baths Still Thrive in Osaka

In a country where nearly every modern apartment boasts a pristine, often technologically advanced bathroom, the continued presence of the public sentō might feel like an anachronism—a relic of a past era. In some regions of Japan, it is. But not in Osaka. Here, the sentō isn’t merely surviving; it’s flourishing as an essential part of social infrastructure. The real question isn’t why people still visit, but why they would ever stop. The answer lies in recognizing that an Osaka sentō provides something your private bathroom never could: a sense of community.

More Than Just a Bath: The Unspoken Role of the ‘Neighborhood Tub’

The sentō’s original purpose arose from necessity. Post-war housing was compact, and having a private bath was a luxury few could afford. The sentō was where everyone—from the local tofu maker to the factory worker—came to wash away the day’s dirt. Yet, as Japan’s economy prospered and private baths became common, the sentō’s role transformed. It shifted from a place of physical cleansing to one of social and mental refreshment. It became what sociologists call a “third place”—neither the domestic pressures of home nor the structured environment of work. It’s neutral ground where social hierarchies vanish, and the simple, shared act of soaking in hot water fosters a unique connection.

Inside, the atmosphere composes a symphony of distinctive sounds: the rhythmic clatter of yellow plastic washbowls on tile floors, the steady flow of water from faucets, the low hum of conversations reverberating off the high, steam-filled ceilings. Here, you hear authentic Osaka-ben, the city’s unique dialect, in its natural setting—not the staged version portrayed on TV, but the casual, humorous, and sometimes brutally honest chatter between neighbors. It’s a place to catch up on gossip, gripe about the Hanshin Tigers’ latest game, or simply sit in comfortable, shared silence, knowing you belong to something larger than yourself.

Decoding the ‘Bandai’: The Gatekeeper’s Domain

Your entry into this world starts at the bandai, the reception desk that acts as the sentō’s command center. Traditionally, this was a raised platform positioned to overlook both the men’s and women’s changing rooms, a design chosen for pure efficiency. Nowadays, many have been modernized to a front-desk style, but the role of the person stationed there remains unchanged. They are gatekeeper, historian, and the friendly face of the establishment. Often, it’s an elderly owner—a man or woman who has occupied that spot for decades, watching generations of families pass through.

This interaction sets the mood, far removed from the silent, transactional exchanges common in Tokyo. In Osaka, handing over your 490 yen (the standard bathing fee) invites conversation. There’s a nod, a greeting, maybe a quick joke. “Maikai arigatou,” they’ll say—“Thanks, as always”—even if it’s only your second visit. They remember faces. They’re not mere employees; they are hosts welcoming you into their space. This simple exchange is your first handshake with the neighborhood. It’s a small but meaningful moment that transforms a routine purchase into a social connection, confirming that you’re not just a customer, but a temporary member of the local community.

The Geography of Steam: Sentō-Hopping Through Osaka’s Neighborhoods

To truly grasp Osaka, you need to know its neighborhoods, each a unique world with its own character, history, and pace. The local sentō perfectly reflects its environment. Moving from one to another is like flipping TV channels, each revealing a different facet of Osaka life. You don’t just experience a different bath; you gain a fresh outlook.

Tenjinbashisuji & Nakazakicho: The Retro Revival

The Neighborhood Vibe

This area is a captivating blend of old and new. Tenjinbashisuji, Japan’s longest shōtengai, is a covered shopping street extending over 2.6 kilometers. It pulses with traditional Osaka commerce, lined with everything from 100-yen croquette stands to vintage kimono shops and lively fishmongers. A short stroll away, Nakazakicho is a labyrinth of narrow alleys filled with beautifully maintained pre-war wooden houses turned into quirky cafes, vintage clothing shops, and indie art galleries. It’s where Osaka’s traditional merchant spirit meets its emerging creative community.

The Sentō Experience

Sentō here often feel like well-preserved time capsules. Picture entering a space that hasn’t changed since the Showa Era. The iconic, grand mural of Mount Fuji painted on tiles above the main bath offers a classic, almost ironic touch in the heart of Kansai. The changing room lockers might still use old-fashioned wooden key tags. In the lobby, bulky coin-operated massage chairs resemble props from a vintage sci-fi movie, and a glass-front fridge hums softly, stocked with little glass bottles of fruit milk and coffee milk, ready to be opened with a special cap. The water has a classic feel—not too hot, not too fancy—a perfectly engineered soak designed for ultimate relaxation after a day of bargaining or creating.

The People You’ll Meet

The clientele here is a rich reflection of the neighborhood. You’ll share the bath with elderly shopkeepers from the shōtengai, bodies tired but spirits high, chatting about the day’s sales. Multi-generational families appear—a grandmother patiently teaching her grandchild how to rinse properly. Younger Nakazakicho residents, tattooed artists and musicians, also come seeking an authentic, analog break from digital life. Conversations range from mackerel prices to the merits of a new local art exhibit. It beautifully showcases how Osaka holds on to its past while welcoming the future, all within the same steamy space.

Nishinari & Shinsekai: Grit, Honesty, and the ‘Denki-buro’

The Neighborhood Vibe

Let’s be straightforward: this neighborhood is nothing if not blunt. Nishinari has a reputation as home to day laborers, a place marked by grit and hardship. Nearby Shinsekai, with its iconic Tsutenkaku Tower, exudes a faded, carnival-like charm. Often misunderstood and seen through lenses of poverty or danger, such views miss the essence. This is arguably one of Japan’s most honest areas, with no pretense. It boasts a strong, unbreakable community forged through shared experience and raw humanity that can be both jarring and deeply moving.

The Sentō Experience

Forget fancy herbal baths or state-of-the-art saunas. Nishinari’s sentō are temples of pure function. The water tends to be scalding hot, perfect for soothing muscles worn from hard labor. The highlight is often the denki-buro, or electric bath: two metal plates on opposite sides of a small tub send a low-voltage electric current through the water, making your muscles tingle and contract. For newcomers, it’s a strange and slightly intimidating experience; for locals, essential therapy. The decor is basic, tiles might be cracked, but cleanliness is immaculate. This isn’t about luxury; it’s about providing a profound, elemental relief—a reset for body and soul.

The People You’ll Meet

Bathing here offers humility and insight. You’ll share the tub with older men, bodies marked by years of construction, shipping, and physical work, sharing stories from their lives. Conversations are blunt. Men joke with gallows humor, gripe about the government, and share simple daily tales. There’s no room for the subtle, indirect communication typical elsewhere in Japan. Here, what you see is what you get. It’s a powerful lesson in resilience and a reminder of the often unseen side of Japan’s economic miracle. You leave not just cleaner, but with a deeper understanding of the city’s social fabric.

Tsuruhashi & Ikuno: The Koreatown Connection

The Neighborhood Vibe

Step off the train at Tsuruhashi and your senses are immediately engulfed. The air is thick with the enticing aroma of Korean barbecue and the sharp, fermented scent of kimchi. The narrow market streets form a lively jumble of vendors selling everything from chijimi (savory pancakes) to vibrant Korean textiles. This is Osaka’s Koreatown, home to one of the largest populations of Zainichi Koreans—ethnic Koreans who have lived in Japan for generations. The energy here is a dynamic fusion, a place where Korean and Osakan cultures don’t just mix, but create something entirely unique.

The Sentō Experience

Reflecting the neighborhood’s heritage, sentō here often feature Korean influences. You might find a potent steam room infused with mugwort (yomogi), a Korean spa staple known for its healing qualities. Bath etiquette signs may be displayed in both Japanese and Korean. Vending machines might offer Korean soft drinks alongside typical Japanese options. The experience is layered, a testament to Osaka’s history as a port city and cultural crossroads. It’s a physical embodiment of the area’s blended identity.

The People You’ll Meet

In the water, linguistic and cultural boundaries fade. Zainichi grandmothers chat in a fluid mix of Korean and Japanese. Local Japanese shop owners and recent Korean immigrants share the space, all equalized by the shared bathing ritual. The sentō acts as a great leveler. Naked and vulnerable, nationality and background become irrelevant. Everyone is simply a neighborhood resident seeking warmth and relaxation. It’s a vivid, living example of how community can form in the simplest ways, proving that a shared hot bath can unite more effectively than any government policy.

The Unspoken Rules of the Osaka Sentō: A Foreigner’s Survival Guide

Stepping into a sentō for the first time can feel intimidating. There are customs, rituals, and an unspoken etiquette that may seem confusing to an outsider. But here’s the secret about Osaka: the rules are less about strict formality and more about common-sense consideration for those around you. And if you make a mistake, someone will likely let you know—not with a glare, but with a friendly, helpful nudge.

Pre-Bath Rituals: More Than Just Washing

Before you even think about entering the main bath, your first stop is the washing area. This is non-negotiable. The large tubs are for soaking, not for cleaning. Find an open station—a stool in front of a faucet and showerhead—and thoroughly scrub your body. Even this step has its own subtle etiquette.

The kake-yu is the first step. Use a washbowl to scoop hot water from the small basin near the entrance and pour it over your body, starting with your feet and working upward. This isn’t just about rinsing off dirt; it helps your body adjust to the bath’s temperature and, more importantly, shows respect for the purity of the shared water. In Osaka, you’ll often see regulars perform this with a practiced, almost ceremonial grace. It’s a quiet acknowledgment of the communal nature of the space. While washing, be considerate of those around you. Splashing is a major faux pas. Keep your shower spray gentle and controlled. When you’re finished, give your stool and surrounding area a quick rinse. The principle is simple: leave the space as clean as, or cleaner than, you found it.

‘Hadaka no Tsukiai’: The Art of Naked Communication

There’s a beautiful Japanese phrase, hadaka no tsukiai, which roughly translates to “naked communion” or “naked friendship.” It captures the idea that when you remove clothes—and with them, external markers of status, wealth, and profession—you connect on a deeper, more human level. This philosophy thrives in Osaka sentō.

Unlike the reserved atmosphere of Tokyo bathhouses where chatting with strangers might be unusual, in Osaka it’s often expected. The easiest way to start a conversation is with a simple remark: “Ee oyu desu ne” (“This is nice hot water, isn’t it?”). This can open the door to surprisingly meaningful discussions. Osakans are known for their curiosity and openness. They might ask where you’re from, what you do, and your thoughts on Osaka. Don’t hesitate. It’s a great opportunity to practice your Japanese and hear genuine opinions on everything from local politics to the best takoyaki spots. And don’t be caught off guard if the famous Osaka ame-chan (candy) culture makes its appearance in the changing room. An obachan (a warm, auntie-like older woman) might offer you a sweet from her purse as you dry off. It’s not odd; it’s a small, sweet welcome and a sign that you’ve been embraced by the community.

Post-Bath Perfection: The Holy Trinity of Milk, Massage Chair, and Television

The sentō experience doesn’t end once you leave the water. The post-bath ritual is equally important and sacred. After drying and dressing, there are three essential steps to reach ultimate relaxation.

First, the drink. Head to a vintage vending machine or cooler and grab a beverage—preferably in a glass bottle. The top choices are coffee milk (kōhī gyūnyū) or fruit milk (furūtsu gyūnyū). There’s something blissful about the cold, sweet liquid refreshing you after the heat of the bath. Second, the massage chair. For a hundred yen, you can enjoy several minutes of vigorous mechanical kneading. Though it may seem old-fashioned, leaning back and letting the chair work its magic is a vital part of the ritual. Finally, the television. The TV in the lobby or changing room serves as a shared hearth. It’s usually tuned to a lively comedy program or a Hanshin Tigers baseball game. People don’t rush off immediately but linger, sitting on worn vinyl benches, sipping their milk, commenting on the broadcast, and gradually readjusting to the outside world. This communal cooldown marks the final moment—a collective sigh before everyone goes their separate ways.

Osaka vs. Tokyo: A Tale of Two Tubs

To truly grasp what makes the Osaka sentō experience so distinctive, it helps to compare it with its Tokyo counterpart. Both cities boast a rich public bath culture, yet each reflects the unique character of its home. While a Tokyo sentō resembles a silent meditation retreat, an Osaka sentō feels more like a lively dinner party.

The Sound of Silence vs. The Roar of the Community

The most noticeable difference is the sound. In many Tokyo sentō, especially contemporary ones, an unspoken rule of silence dominates. It’s a place for quiet reflection, a personal escape from the city’s overwhelming sensory overload. Visitors tend to keep to themselves, focusing on their own private relaxation ritual. In contrast, silence in Osaka can seem odd, even awkward. The constant buzz of conversation is the norm. The bath acts as a social catalyst, designed to foster interaction. The aim is not only to soothe your own body but to do so collectively, sharing stories and laughter along the way.

Function vs. Personality

In recent years, Tokyo has witnessed the rise of “designer sentō”—old bathhouses transformed by architects into sleek, minimalist, and highly Instagrammable spaces. These are visually stunning and spotless but sometimes feel more like modern art galleries than community centers. They appeal to a younger crowd who value aesthetics and a more individualistic experience. Osaka, however, seems to treasure its sentō precisely for their resistance to change. Many remain unapologetically old-fashioned, proud of their Showa-era tiles and vintage fixtures. Their value lies not in trendiness but in their history and the character accumulated through decades of use. They are living museums of everyday life, and locals wouldn’t want them any other way. The charm resides in the imperfections, the stories etched into every cracked tile and faded mural.

Indirect Politeness vs. Direct Friendliness

This contrast extends to enforcing the rules. If you accidentally breach etiquette in a Tokyo sentō—such as entering the main tub without rinsing first—you’ll likely be met with a cold glance or simply ignored. The correction is quiet and exclusionary. In Osaka, the reaction is quite different. An obachan is more apt to approach you directly, perhaps giving you a light, playful tap while grinning and saying, “Anata, akan de! Saki arayanasai!” (“Hey, you can’t do that! You need to wash first!”). Though it might be startling at first, it’s important to recognize the intent. It’s not meant to be harsh or humiliating. It’s straightforward, instructive, and, above all, inclusive. They’re not excluding you for not knowing the rules; they’re actively helping you learn so you can fully participate. It’s a gesture of tough, practical love—the Osaka way.

How Sentō-Hopping Rewires Your Understanding of Osaka

Spending your weekends exploring Osaka’s bathhouses does more than simply leave you clean and relaxed. It fundamentally transforms your connection to the city. It takes you off the main tourist routes and immerses you directly in the rhythms of everyday life. This process reshapes your perceptions and deepens your appreciation for this complex, contradictory, and wonderfully human place.

Seeing Beyond the Tourist Traps

The search for a new sentō inevitably brings you into residential neighborhoods you’d otherwise have no reason to visit. You’ll find yourself wandering through quiet suburbs, busy working-class areas, and tucked-away alleyways. On the walk from the station to the bathhouse, you witness the real city: family-run hardware stores, local butchers selling fresh croquettes, small parks filled with children’s voices in the late afternoon. The sentō acts as the heart of this community. After your bath, feeling refreshed and open, the neighborhood reveals itself as a place to engage with, not just observe. You might grab a draft beer at a tiny tachinomi (standing bar) next door, sharing a counter with the same people you just shared a tub with. You become part of the local rhythm, even if only for an evening.

Learning to Embrace the ‘Uncool’

Tokyo often represents sleek, sophisticated coolness—a city of impeccable design, cutting-edge trends, and refined aesthetics. Osaka, in contrast, defines itself differently. There’s a deep pride in being unpretentious, practical, and a little rough around the edges. The sentō perfectly embodies this spirit. It’s not about fashion but comfort, community, and a type of functionality that holds its own profound beauty. Learning to appreciate the worn-out vinyl benches, rumbling massage chairs, and unapologetically retro decor is to embrace the Osakan value system. It teaches you to find charm in what is genuine and lasting, rather than what is new and fleeting.

The Ultimate Lesson in ‘Ningenmi’

If one word captures the essence of the Osaka sentō experience, it’s ningenmi. Though difficult to translate directly, it conveys ideas like “human-ness,” “human warmth,” or “the quality of being human.” It stands in opposition to sterility, formality, or rigidity. It’s the messy, humorous, compassionate, and sometimes loud reality of people living together. In the sentō, with everyone stripped of their daily armor, ningenmi is fully visible. It’s in an old man helping a friend scrub his back, in shared laughter over a silly TV show, and in easy conversations between strangers. You don’t just learn about Osaka’s culture; you absorb it through your skin. Soaked in hot water and surrounded by the city’s raw humanity, you begin to understand Osaka not just with your mind, but with your whole being.