In the grand, neon-drenched theater of Osaka, Namba is the dazzling main stage. It’s a place of colossal glowing crabs, of thunderous pachinko parlors, and rivers of people flowing through covered shopping arcades. It is spectacular, undeniable, and utterly overwhelming. But for those who seek the city’s true rhythm, its unvarnished, beating heart, the real performance begins just behind the curtain. Welcome to Ura Namba, which literally translates to “Back Namba.” This is not a single street but a sprawling, intoxicating web of narrow lanes and hidden passages nestled behind the Nankai Namba Station. It’s a world away from the polished facades and tourist-heavy thoroughfares, a district where the air is thick with the savory smoke of grilling meat, the clatter of ceramic bowls, and the warm, unpretentious laughter of locals unwinding after a long day. Ura Namba is the city’s communal living room, its culinary playground, a place where standing-room-only bars and tiny, lantern-lit izakayas offer a portal into the authentic spirit of Osakan nightlife. This is where the philosophy of kuidaore—to eat and drink until you drop—is not just a saying, but a way of life, practiced nightly with joy and camaraderie. It’s a place that asks you to get a little lost, to follow your nose, and to discover that the best of Osaka is often found in the smallest of spaces.

The Electric Pulse of Osaka’s Hidden Heart

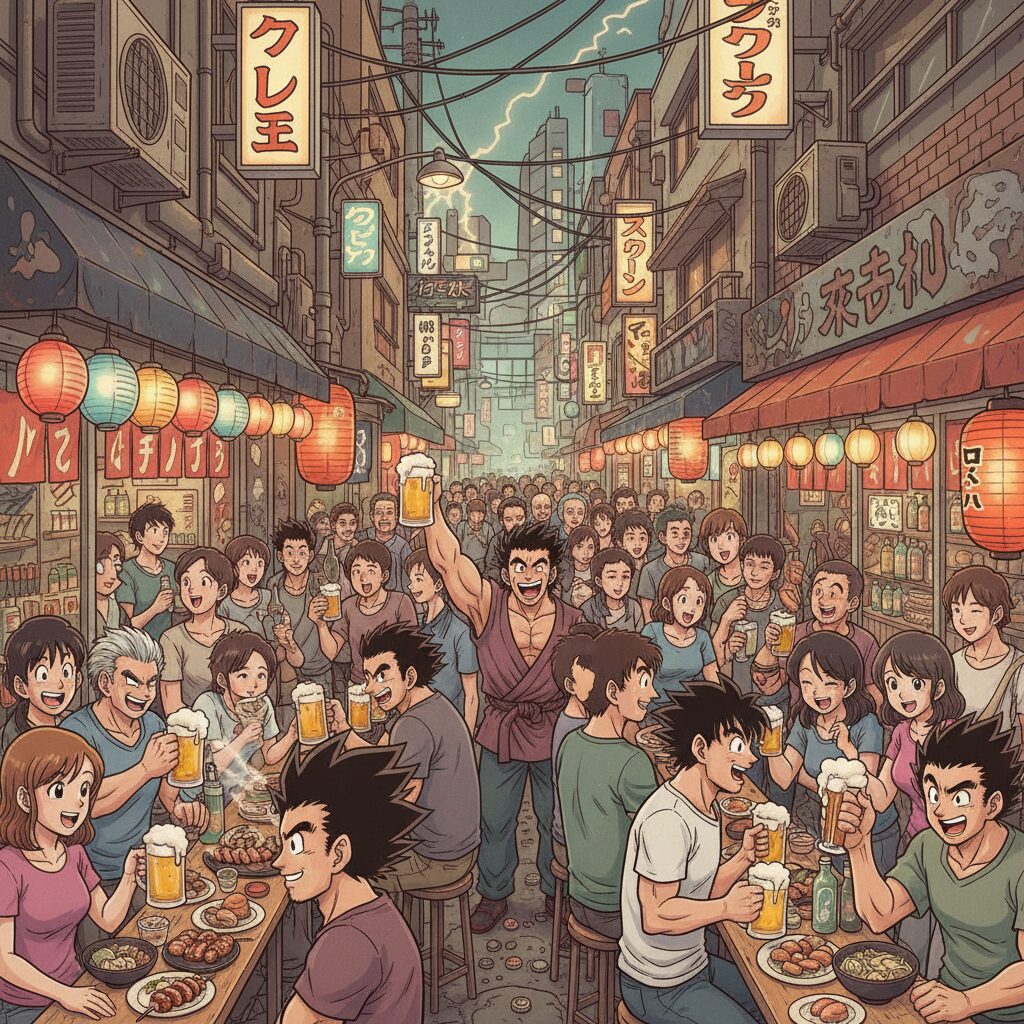

To step into Ura Namba is to immerse yourself in a beautifully orchestrated chaos that awakens the senses. This is not a passive encounter; it’s a fully engaging plunge into a vibrant, living ecosystem of culinary pleasures. The energy here is tangible, a steady, hum-like pulse of human connection rising and falling with the evening’s flow. The area is designed on a human scale, where the narrow alleys encourage a feeling of closeness. You’ll find yourself rubbing shoulders with salarymen loosening their ties, young couples sharing sashimi, and old friends reconnecting over frothy beers. The district resists the sterile perfection of modern commercialism, instead flourishing with a lived-in, organic charm. Tangled wires dangle overhead, mismatched stools spill onto the sidewalks, and the warm glow of red paper lanterns, or akachochin, bathes everything in a nostalgic light.

A Symphony of Senses

The soundscape of Ura Namba is as rich and layered as its culinary offerings. The dominant note is the lively sizzle from countless grills—the crisping chicken skin over charcoal, the searing pork belly on a hot teppan plate, the okonomiyaki batter hitting a well-seasoned griddle. This rhythm is accented by the sharp clatter of cooking utensils, the rhythmic shake of a cocktail mixer, and the satisfying thud of a heavy beer mug on wood. Above this culinary orchestra rises the chorus of human voices: cheerful cries of “Irasshaimase!” (Welcome!) at every door, warm and enthusiastic. Sudden bursts of laughter ring out from packed bars, blending with the gentle murmur of conversations in the distinct, melodic Kansai dialect. The clinking of glasses as strangers toast one another is a frequent sound in the convivial atmosphere of these standing bars. It’s a sound unmistakably Osaka—loud, uninhibited, and warmly friendly.

Even more enticing are the aromas, a complex perfume telling the neighborhood’s story. The most prominent scent is smoky—not the harsh smoke of pollution, but the rich, fragrant aroma of yakitori grilling. This smell clings to the air, a mouthwatering promise of the meal ahead. Layered within are other notes: the sweet soy and mirin glaze of teriyaki; the sharp, briny tang of fresh seafood on ice; the earthy, comforting aroma of dashi broth simmering in pots; and the slightly sweet, yeasty scent of sake being warmed. Wander further and you might catch sizzling garlic, a spike of spicy ginger, or the deep, fermented funk of miso. Each alley and doorway offers a new olfactory journey, guiding you not by sight but scent, drawing you ever onward to your next delicious discovery.

The Visual Language of the Alleyways

Visually, Ura Namba is a rich mosaic of textures and details. The architecture is a patchwork of small, two-story buildings that wear their age with pride. They crowd together so tightly they seem to lean on one another for support. Look out for the noren, traditional fabric curtains hanging in the doorways. These are more than decoration; they signal quality. A clean, crisp noren hints at what lies within—a deep blue curtain for a seafood spot, a rustic brown for a traditional izakaya. Peeking beyond the noren reveals an inviting world: a focused chef meticulously skewering chicken, a bartender polishing glasses to a shine, patrons packed tightly around counters, voices animated in lively conversation. The signage is an art form in itself. Hand-painted wooden signs with elegant calligraphy compete with buzzing retro neon lights and simple handwritten menus taped to the windows. This vibrant visual density creates a feeling of endless discovery, the sense that a hidden gem awaits behind every door or down every unmarked alley.

Unraveling the Threads of Time: The Soul of Ura Namba

Ura Namba’s vibrant present is firmly anchored in Osaka’s rich history. This neighborhood did not arise from a modern developer’s plan; it developed naturally, shaped by the needs and spirit of its people. To appreciate its appeal is to grasp the city’s own story—a heritage marked by commerce, resilience, and a passionate love for good food and company. For centuries, Osaka was known as Tenka no Daidokoro, the “Nation’s Kitchen,” serving as the central hub where rice and goods from across Japan were collected and distributed. This legacy nurtured an intricate food culture and a community with refined tastes who cherished communal dining.

From Post-War Markets to Culinary Hubs

Much of modern Ura Namba’s character dates back to the post-war era. Near Nankai Station, one of the city’s key transport centers, black markets and open-air stalls, or yatai, emerged to feed the recovering populace. These modest, makeshift stands offered simple, hearty, and affordable dishes like grilled offal (horumon) and savory stews. They served as places of necessity but also of community, where people came together to share a meal and comfort. As Japan’s economy grew, these temporary stalls gradually transformed into the permanent, small-scale establishments found today. Retaining their unpretentious nature and affordable prices, they also refined their menus. The area’s labyrinthine layout is a direct legacy of these origins, preserving narrow market lanes that were never straightened or turned into wide, sterile boulevards. This history is embedded in the very fabric of the neighborhood, giving it an authenticity that cannot be replicated. You can sense it in the well-worn wooden counters, polished smooth by decades of elbows, and in recipes like doteyaki, handed down through generations of the same families.

The Philosophy of Tachinomi: A Vertical Society

The widespread presence of tachinomi, or standing bars, in Ura Namba is yet another intriguing cultural tradition. In a densely populated country where space is always limited, tachinomi represents a model of efficiency. By removing chairs, proprietors could serve more customers within a small area, keeping prices low and turnover high. Historically, these bars were quick stops for laborers and businessmen to enjoy a drink and a bite on their way home. But tachinomi is more than just a space-saving measure; it creates a distinct social atmosphere. Standing promotes a more fluid, egalitarian environment. There are no assigned seats or hierarchies. Everyone stands shoulder-to-shoulder, sharing the same counter space. This closeness makes it easy to start a conversation with those nearby. In a society sometimes known for its reserve, tachinomi is a place where social barriers break down. An office worker may find themselves chatting with a construction worker, or a young student with a retired shop owner. It is a microcosm of the city itself, where people from all walks of life briefly connect over a mutual love of great food and drink. It is a vertical society—community built one drink, one skewer, and one conversation at a time.

Your First Steps into the Labyrinth: A Practical Guide

For those visiting Ura Namba for the first time, the area can feel both thrilling and somewhat intimidating. Its lack of clear signage and maze-like layout are part of its unique charm, though they can make it challenging to find your way. The key is to embrace the uncertainty with a sense of adventure. The best way to enjoy Ura Namba is to simply explore on foot. Set aside your map for a bit and let the sights and aromas lead you. The main cluster of alleys lies just east and south of Nankai Namba Station, especially around the area known as the Misono Building, a retro complex that serves as a landmark itself. The ideal time to visit is early evening, around 6 PM, when the lanterns begin to glow, grills start firing up, and the first after-work crowd arrives, creating a lively atmosphere. Arriving at this time often gives you the chance to grab a spot at a popular bar before the bigger crowds show up later in the night.

Decoding the Noren Curtain

The noren curtain is your initial point of contact with an establishment, and learning how to read its signals is essential. A noren hanging in the doorway means the place is open; if it’s removed, they are closed. The condition of the noren often reveals a lot about the establishment. A stained, smoke-tinted curtain might signal a long-established, beloved yakitori spot, while a clean, minimalist one could indicate a modern sake bar. Don’t hesitate to peek inside. A quick look will give you a good sense of the atmosphere and, most importantly, whether there’s room inside. If it’s packed tight with no space to move, it’s best to move on and try another location. But if you spot a small gap at the counter, that’s your invitation. A gentle nod combined with a questioning glance toward the staff usually suffices. They will either wave you in or, with an apologetic gesture, indicate that they’re full.

Reading the Signs, Spoken and Unspoken

Language can pose a barrier, but in Ura Namba, it’s rarely insurmountable. While English menus aren’t common everywhere, many places are used to international guests. Pointing is perfectly acceptable and often encouraged. Numerous bars display their daily specials on handwritten strips of paper pasted to the walls or have plastic food models in a showcase. These are your best guides. Point at what appeals to you, smile, and say a simple “Kore, kudasai” (This one, please). An important, unspoken rule in a crowded tachinomi bar is to be mindful of your space. Keep your bag and coat close to you. When you’re done, avoid lingering for too long. These spots rely on a steady turnover, so the polite approach is to enjoy your food and drinks and then make room for the next customer. This custom of hashigo-zake, or bar hopping, is a fundamental part of the Ura Namba experience. The aim isn’t to spend the entire evening in one place but to sample the distinct flavors and atmospheres of several different venues.

The Currency of Connection: Ordering and Paying

Most places in Ura Namba accept cash only. It’s a good idea to carry a sufficient amount of yen to prevent any awkward moments. When you’re ready to pay, catch the staff’s eye and say “Okanjo, onegaishimasu” (The bill, please) or simply cross your index fingers to form an “X,” the universal gesture for the check in Japan. In some tachinomi bars, you pay as you order by placing money in a small tray on the counter each time. In most izakayas, payment is settled at the end. One aspect that often surprises newcomers is the otoshi or tsukidashi, a small mandatory appetizer served with your first drink. It also acts as a table charge. Don’t view it as a rip-off; consider it part of the experience. It’s usually a simple yet tasty little dish, like simmered vegetables or a small serving of potato salad, meant to whet your appetite while you wait for your main order.

A Culinary Deep Dive: The Flavors That Define the Night

At its essence, Ura Namba is a tribute to food. It’s a place where humble, straightforward ingredients are transformed into something deeply gratifying through skill and tradition. The menus tend to be focused, with many establishments honing in on just one or two types of cuisine, perfected over years, if not decades. This specialization is a hallmark of Japanese culinary culture, guaranteeing that whatever you’re eating is of the highest quality.

The Holy Trinity: Kushikatsu, Doteyaki, and Takoyaki

If Ura Namba had a signature trio of dishes, these would be it. They represent the quintessential flavors of Osaka, the tastes locals crave and visitors long for. They are hearty, flavorful, and perfectly crafted to enjoy alongside a drink.

Kushikatsu: The Art of the Skewer

Kushikatsu are deep-fried skewers of meat, seafood, and vegetables. The idea is simple, but the execution is a true art form. Each ingredient is carefully skewered, dipped in a light panko breadcrumb coating, and fried to a perfect golden brown. The result is a crispy, non-greasy bite that is intensely flavorful. Part of the enjoyment comes from the huge variety. You can find everything from pork loin (tonkatsu) and chicken meatballs (tsukune) to shrimp, scallops, lotus root, shiitake mushrooms, and even cheese. The skewers are served with a communal pot of thin, sweet-and-savory dipping sauce. This is where the single most important rule of kushikatsu applies: NO DOUBLE-DIPPING. For hygiene reasons, you dip your skewer once, and only once, into the sauce. If you want more sauce, use the provided slice of raw cabbage to scoop it up and drizzle it over your plate. Breaking this rule is a major faux pas, so dip carefully.

Doteyaki: A Simmered Bowl of History

Doteyaki is a rich, comforting stew that captures the soul of Osakan cooking. It’s made from beef sinew, a cheap cut of meat, slow-cooked for hours in a broth of miso, mirin, sake, and dashi until it becomes incredibly tender and gelatinous, almost melting in your mouth. The name doteyaki comes from the practice of lining the pot’s interior with miso paste, creating a “dote” or riverbank, which slowly dissolves into the stew, infusing it with deep, complex flavors. It’s often topped with a generous sprinkle of chopped green onions, offering a sharp, fresh contrast to the stew’s richness. Served in a small bowl, it pairs perfectly with a cold beer or a glass of shochu, warming you from the inside out.

While takoyaki (battered octopus balls) is better known as a street food, many small izakayas in Ura Namba serve their own unique versions. Here, takoyaki is often elevated, accompanied not just by the typical takoyaki sauce and mayonnaise, but perhaps with a sprinkle of high-quality salt or a side of dashi for dipping (akashiyaki-style). Watching chefs expertly flip the batter in their special cast-iron pans is a captivating culinary performance.

Beyond the Staples: Seafood, Grills, and More

The culinary scene in Ura Namba goes far beyond these three staples. Seafood enthusiasts will be delighted. Look for small bars with refrigerated cases out front, proudly showcasing the day’s catch on crushed ice. Here, you can enjoy incredibly fresh sashimi and sushi, or have your chosen fish simply grilled with salt (shioyaki) to highlight its natural flavor. Yakitori spots are another neighborhood mainstay. The air around these places is thick with fragrant smoke from Binchotan charcoal. Menus offer a head-to-tail exploration of chicken, from tender thigh meat (momo) and crispy skin (kawa) to more adventurous parts like heart (hatsu) and gizzard (sunagimo). Each skewer is seasoned with either salt (shio) or a sweet soy glaze (tare), grilled to perfection, and served piping hot. You’ll also find establishments specializing in teppanyaki, where chefs cook on a large iron griddle before you, serving everything from sliced beef to stir-fried noodles (yakisoba). The variety is endless, inviting you to move from one spot to the next on a self-guided food adventure.

The Art of the Drink: Quenching Osaka’s Thirst

In Ura Namba, food and drink are inseparable companions in a nightly ritual. The drinks menu at a typical izakaya is crafted to enhance the bold, savory flavors of the dishes. The selections tend to be straightforward, emphasizing beverages that are refreshing, clean, and won’t overpower the food. Drinking is just as social as eating, serving as a lubricant for conversation and a catalyst for camaraderie.

Navigating the World of Sake and Shochu

For many visitors, ordering Japanese alcohol can feel intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be. Sake, or nihonshu as it’s called in Japan, is a fermented rice wine available in a vast array of styles. You don’t need to be an expert to enjoy it. A simple way to start is by choosing whether you want it hot (atsukan) or cold (reishu). Cold sake typically highlights the more delicate, fruity, and floral notes of premium varieties like ginjo and daiginjo. Hot sake usually comes from more robust, earthy styles such as junmai or honjozo, offering comforting warmth on a cool evening. Sake is traditionally served in a small ceramic flask called a tokkuri and poured into tiny cups called ochoko. The custom is to pour for your companions and let them pour for you, never pouring your own drink.

Shochu is another favored option. This distilled spirit can be made from various ingredients, most commonly barley (mugi), sweet potatoes (imo), or rice (kome). It has a higher alcohol content than sake and is often served on the rocks (rokku), mixed with cold water (mizuwari), or with hot water (oyuwari). Imo shochu features a distinctly earthy, intense flavor, while mugi shochu tends to be lighter and smoother. Sampling a glass offers a great way to explore another facet of Japanese drinking culture.

The Ubiquitous Highball and the Perfect Beer

Step into any izakaya in Ura Namba, and you’re sure to see patrons enjoying two staples: beer and highballs. Japanese draft beer (nama biiru), typically a crisp, clean lager from brands like Asahi, Kirin, or Sapporo, reigns supreme as the first drink. Served ice-cold in a frosted mug, it’s the ideal refreshment to cut through the richness of fried and grilled dishes. Its effervescence refreshes the palate, prepping you for the next delectable bite. The Japanese Highball has experienced a huge surge in popularity and is the favorite choice for many. It’s a deceptively simple mix of Japanese whisky (usually Suntory Kakubin), highly carbonated soda water, and a twist of lemon, served in a tall glass filled with ice. Light, refreshing, and endlessly drinkable, it pairs excellently with food without leaving you feeling too full. Its straightforwardness is its charm, making it a modern emblem of Japanese bar culture.

An Evening in Ura Namba: A Narrative Journey

To truly grasp the magic of Ura Namba, let’s imagine a hypothetical evening—a bar-hopping journey that captures the flow and rhythm of the night. This is a trip not only between places but also through different moods, flavors, and experiences, perfectly illustrating the hashigo-zake culture.

From Sunset to Last Call

The night begins as the sun sets, casting long shadows along the narrow alleys. The oppressive humidity of the summer day fades, replaced by an electric sense of anticipation. The first stop is vital; it sets the tone for the entire night. We’re searching for a classic tachinomi, a spot with a worn wooden counter and a lively crowd already spilling outside.

The Warm-Up: A Tachinomi Welcome

We notice a place adorned with a faded blue noren and a glowing red lantern inviting us in. Peering inside, we spot a small opening at the counter. Sliding in, we find ourselves shoulder-to-shoulder with office workers. The air is warm and filled with the aroma of simmering dashi. We begin with the classic order: “Nama futatsu!” (Two draft beers!). The beers arrive quickly, perfectly chilled with a thick, creamy foam topping. We savor a long, satisfying sip. For food, we point to the large pot bubbling at the counter’s corner—it’s the house doteyaki. A bowl is swiftly filled and handed to us, garnished with a lively sprinkle of green onions. The beef sinew is incredibly tender, and the miso broth richly savory with a touch of sweetness. It’s a flawless opening act. We follow with a few kushikatsu skewers—a juicy pork piece, a tender quail egg, and a sweet onion slice, all flawlessly fried. We carefully dip them (just once!) into the communal sauce, the crispy coating cracking with each bite. After about thirty minutes, we’ve finished our beers and food. We pay at the counter, share a nod and smile with the chef, and step back into the alley, feeling energized and ready for the next stop.

The Main Event: Settling into an Izakaya

For our second stop, we want a change of pace—a place to sit and explore a broader menu. We wander deeper into the maze, down a particularly narrow passage, and discover a small izakaya with a beautifully hand-carved wooden sign. Inside, it’s quieter and more intimate than the tachinomi. We take two seats at the counter, offering a front-row view of the chef at work. This time, we decide to dive into the world of sake. We ask the chef for his recommendation (osusume), and he pours us a cold, crisp junmai ginjo from a local Osaka brewery. It’s clean and slightly fruity, pairing perfectly with the assorted sashimi he prepares—gleaming slices of fatty tuna, sweet shrimp, and firm sea bream. The quality is outstanding. We follow with grilled chicken thighs, the skin blistered and crispy from the charcoal grill, the meat juicy and smoky. Conversation flows easily, both between us and with the chef, who shares stories about the fish he bought at the morning market. We linger longer here, ordering another flask of sake and a few more small dishes. It’s a completely different tempo from the first bar—more relaxed, focused on savoring every bite. As the night deepens, we make a final stop, perhaps a tiny, specialized bar for a nightcap—a glass of shochu or a perfectly made highball—before dissolving back into the neon glow of greater Namba, our senses alive and stomachs full, carrying with us the authentic, unforgettable taste of Osaka.

Beyond the Lantern’s Glow: Final Thoughts from a Fellow Traveler

Ura Namba is much more than a mere collection of bars and restaurants. It stands as a living museum of Osakan culture, embodying the city’s deep-rooted passion for food, drink, and human connection. Having spent countless hours exploring the hutongs of Beijing and the night markets of Taipei, I recognize a beautiful, resonant echo in these Japanese alleyways. There is a shared East Asian appreciation for the magic found in these small, unpretentious spaces—the belief that the best food and most authentic experiences are discovered not in grand dining halls, but in the humble, vibrant corners of a city. What distinguishes Ura Namba is its distinctive mix of lively energy and meticulous craftsmanship. It’s a place where you can enjoy a loud, raucous night while savoring food prepared with an almost reverential attention to detail. Navigating Ura Namba is like participating in a nightly ritual, a celebration of community. It’s about the joy of discovery, the thrill of uncovering a hidden gem, and the simple pleasure of sharing a meal with friends, both old and new. So, when you visit Osaka, by all means, see the famous sights. But once evening falls, put away your map, follow the scent of charcoal smoke, and let the warm glow of a paper lantern guide you into the heart of Ura Namba. Raise a glass, take a bite, and toast to the electric, indomitable, and utterly delicious spirit of the city.